Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

House Republicans try to choose a speaker

There was a time not that long ago (most of the last 100 years, give or take) when Republicans were considered the party of discipline and Democrats the party of “circular firing squads,” civil wars, or whatever other synonym for dysfunction was preferred. These stereotypes were unfair only insofar as they were a bit of an exaggeration, but they were based on some kernels of truth.

As far back as the 1920s and '30s, the humorist Will Rogers made a living commenting on Democratic disunity. He famously quipped, “I’m not a member of any organized political party … I’m a Democrat.” And “Democrats never agree on anything, that’s why they’re Democrats. If they agreed with each other, they’d be Republicans.” His quotes have been referenced time and again by political reporters in more recent decades, too.

We can point to a lot of reasons for the dysfunction. Democrats have become a "big tent" party, and big tents are held up with a lot of different poles. A bigger tent makes room for more religions, races, and social identities, which can bring competing ideologies but certainly different lived experiences and personal perspectives. Democrats are also more liberal and thus challenge the status quo, while conservatives try to preserve it.

We could go on and on — entire political science careers have focused on this issue — but we won’t. Because right now the narrative has flipped more dramatically than an O’Henry short story.

For several years running, Democrats in the House have been largely united in both the majority and the minority under the leadership of Nancy Pelosi. This cohesion has produced a stunning list of legislative accomplishments (and successful resistance to Republican presidential initiatives like privatization of Social Security). When Pelosi and other senior party leaders stepped down after the 2022 midterms, we might have expected a wild free-for-all for their replacements. But those elections contained about as much drama as the ones in North Korea.

Instead, it is the Republicans who are being pulled in multiple directions by a caucus wearing chaos as a badge of honor. At the time of this writing, it doesn’t seem that Kevin McCarthy has locked up the votes for speaker. Even if he gets there, he might have had to make so many concessions that his daily hold on leadership would be as tenuous as a candle flame in a hurricane. He has few votes to spare. That’s why his retaining the likes of George Santos, the man who lied about his entire resume and family history, is so important.

Stepping back from the machinations of House leadership, the battle McCarthy faces and embodies is a symptom of a more fundamental rot within the Republican Party. In the coverage of McCarthy’s winding path to speaker, most of what we hear about is power, not policy. For what does McCarthy stand? What does he want to do with the speakership? What about his supporters? And what about the band of Republican holdouts seeking to exact their pound of flesh?

For that matter, what legislation did the most recent Republican president want to pass with his power? What were his priorities other than a border wall and “owning the libs”? And what of those of Mitch McConnell and other Republican leaders in Congress? Tax cuts, for sure. And stacking the federal judiciary. The courts offer a way for Republicans to get the policies they want without having to legislate — from partisan gerrymandering to abortion bans to gutting environmental regulations.

Whatever one thinks about the Democrats’ agenda, one cannot deny that they like passing bills and want majorities in the House and Senate to do just that. Using the legislative branch to legislate: what a concept. Democrats have compromised with Republicans to get the votes they needed. They’ve even voted against their short-term political self-interest — as with Obamacare, when many Democrats in Congress supported a bill they knew was unpopular at the time and would be used against them in the upcoming elections.

You hear almost nothing about legislation from Republican representatives these days. It’s all about who is going to have the power and not how they want to use it to help the American people. We can expect investigations into the Biden administration for sure, along with dangerous games of chicken around the debt ceiling, aid to Ukraine, and other pressing issues. Even Newt Gingrich had his Contract with America. This crowd mostly has their Fox News auditions in mind.

Perhaps this is why Republicans are having such trouble with the speaker vote. Because when you stand for nothing other than the raw exercise of power, the only thing you’re voting on is power itself. And who wants to give that up?

The current fight over Republican House leadership may strike many Americans as boring, “inside the beltway” blather that in the great scheme of things doesn’t really amount to much. But it does, if you believe that our elected representatives in Washington should be deciding substantive policy issues to benefit the country and acting as responsible participants in our constitutional system of checks and balances.

As far removed as this dynamic may seem from the concerns of daily life, it matters. A lot. And there may be ample proof of that in the months and years to come.

READ MORE  Ukrainian servicemen prepare cannon shells before firing them towards positions of Russian troops in Donetsk region, Ukraine January 1, 2023. (photo: Anna Kudriavtseva/Reuters)

Ukrainian servicemen prepare cannon shells before firing them towards positions of Russian troops in Donetsk region, Ukraine January 1, 2023. (photo: Anna Kudriavtseva/Reuters)

Although the figures remain contested, Russian bloggers’ and journalists’ estimates range between 200 and 600 casualties, the Wall Street Journal reports. Igor Girkin, a former soldier who led Russian separatist forces in eastern Ukraine, criticized the Russian government for placing military equipment near barracks. “The number of dead and wounded goes into many hundreds,” Girkin claimed.

Russian state media sought to allay concerns about the attack by releasing a statement claiming that only 63 troops had died in it.

Ukrainian leaders have yet to announce a death toll, but military sources contend that 400 Russian soldiers were killed and an additional 300 were wounded in the barrage.

The strike comes on the heels of competing year-end messages delivered by Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky and Russian President Vladimir Putin to their respective nations. While Zelensky sought to strengthen Ukraine’s resolve in the face of Russian attacks on civilian areas, Putin echoed his commitment to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

“On February 24, millions of us made a choice. . . . Not a white flag, but a blue and yellow flag. Not escaping, but meeting. Meeting the enemy. Resisting and fighting,” Zelensky said during his video address, released just before midnight on New Year’s Eve.

The day before, Putin had claimed that “it was a year of truly pivotal, fateful events,” while visiting a military district in southern Russia. “They have become the frontier that lays the foundation for our common future, our true independence. This is what we are fighting for today, protecting our people in our own historical territories, in the new regions of the Russian Federation,” Putin had stated.

The Ukrainian strike relied on American-supplied HIMARS rocket systems designed by Lockheed Martin.

READ MORE  Donald Trump. (photo: Scott Olson/Getty Images)

Donald Trump. (photo: Scott Olson/Getty Images)

While one of Trump’s main businesses was found guilty of criminal tax fraud earlier this month, Trump himself has so far not been accused of doing anything illegal with his taxes and personal accounting.

But that’s raising more urgent questions about the fairness of the U.S. tax code and tax regulations, which number in the millions of words and in the case of Trump proved effectively unenforceable.

Advocates for tax reform say that a shift in mindset is needed, that a flawed conception of taxation as punitive and economically destructive is what allows for the sort of serial tax avoidance on display in the Trump tax returns.

“With the release of Donald Trump’s tax returns we have learned that he did not pay any federal income taxes [in some years],” Frank Clemente, director of tax advocacy group Americans for Tax Fairness, said in a statement to The Hill.

Clemente said that Trump’s tax avoidance was made possible by “a loophole-ridden tax system in need of fundamental change.”

Trump on Friday touted his ability to use the tax code to his advantage, specifically praising his use of business losses to wipe out his own personal tax bill.

“The ‘Trump’ tax returns once again show how proudly successful I have been and how I have been able to use depreciation and various other tax deductions as an incentive for creating thousands of jobs and magnificent structures and enterprises,” Trump said in a statement.

In an apparent violation of IRS policy, which mandates that presidents receive regular audits, U.S. tax collectors were not auditing Trump on an annual basis, according to the House Ways and Means Committee report released last week.

The reason for that isn’t clear, but the complexity of Trump’s financial situation and the tax laws that enable it may have been to be too much for the IRS to handle with the resources dedicated to it.

“The individual tax return of the former President included the activities of hundreds of related and pass-through entities, numerous schedules, foreign tax credits, and millions of dollars in [net operating loss] carryforwards,” the Ways and Means report found.

The lone IRS agent assigned to one of Trump’s audits noted that “the lack of resources was the reason for not pursuing certain issues on the former President’s returns.”

“With over 400 flow-thru returns reported on the form 1040, it is not possible to obtain the resources available to examine all potential issues,” an internal IRS memo stated, according to the report.

While the committee dumped thousands of pages of documents on Trump’s taxes on Friday, it did not release IRS audit files along with them — a notable omission since the reason for obtaining and releasing Trump’s returns was supposed to be IRS oversight.

“Where are the IRS workpapers?” tax expert Steve Rosenthal said in an email to The Hill. “I thought the Ways and Means Committee was sharing Trump’s tax returns to allow the public to assess the IRS audit. The Joint Tax Committee reported the IRS audit was abysmal, which seems correct. But Joint Tax used the IRS workpapers to illuminate. We ought to see them also.”

The IRS is set to receive $80 billion in additional funding over the next decade, nearly doubling the operating budget of the agency on an annual basis and improving its capacity to audit complex business operations such as those belonging to Trump.

But a structural discrepancy in the U.S. tax system between the way workers and business owners are taxed means that this new money for law enforcement might not be as effective as more legal reforms.

“Under the current system, American workers pay virtually all their tax bills while many top earners avoid paying billions in the taxes they owe by exploiting the system,” Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen said in 2021.

“At the core of the problem is a discrepancy in the ways types of income are reported to the IRS: opaque income sources frequently avoid scrutiny while wages and federal benefits are typically subject to nearly full compliance. This two-tiered tax system is unfair and deprives the country of resources to fund core priorities,” she said.

Tax reform advocates say it’s time to be taxing wages and capital in the same way.

“We should tax income from wealth the same as income from work. Very little of Trump’s money was earned by working—most was just ‘earned’ when he sold assets he inherited that had grown in value,” Amy Hanauer, director of the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, wrote in an editorial for Newsweek.

“This is backwards. Lawmakers should equalize these rates so that someone who wakes up at 6 a.m. and trudges to work in the rain doesn’t pay a higher rate than someone who sits in their inherited mansion watching the stock portfolio they were given grow,” she wrote.

Speaking in November, Fred Goldberg, who was IRS commissioner under George H.W. Bush, said that simplifying the U.S. tax code has long been a moonshot for lawmakers.

“That’s been the holy grail for 40 years,” he said.

Beyond the policy questions raised by Trump’s labyrinthine returns, their release represents the latest chapter in years of political sparring over the former president’s business career and the tactics he used to amass his wealth and fame.

Throughout his first political career, Trump and his supporters pledged he would be a ruthless deal-maker on behalf of the American people. While Trump attributed his success to a tireless work ethic and unique ability to dominate negotiations, a series of financial records, media reports and lawsuits exposed his heavy reliance on tax credits, bankruptcy litigation and fraud to build a real estate empire.

Democrats often criticized Trump for claiming to be a virtuosic businessman despite declaring bankruptcy four times and amassing billions of dollars in debt to finance a string of deals. They also sought Trump’s tax returns to assess the true nature of his wealth and the depth of his financial connections abroad.

“As the public will now be able to see, Trump used questionable or poorly substantiated deductions and a number of other tax avoidance schemes as justification to pay little or no federal income tax in several of the years examined,” said Rep. Don Beyer (D-Va.) in a Friday statement.

Trump and his Republican supporters in Congress, however, defended the former president’s business practices as a basic part of operating in real estate. The former president anointed himself the “king of debt” in 2016 amid frequent criticism of his past bankruptcies, which he called an effective way of keeping his business going.

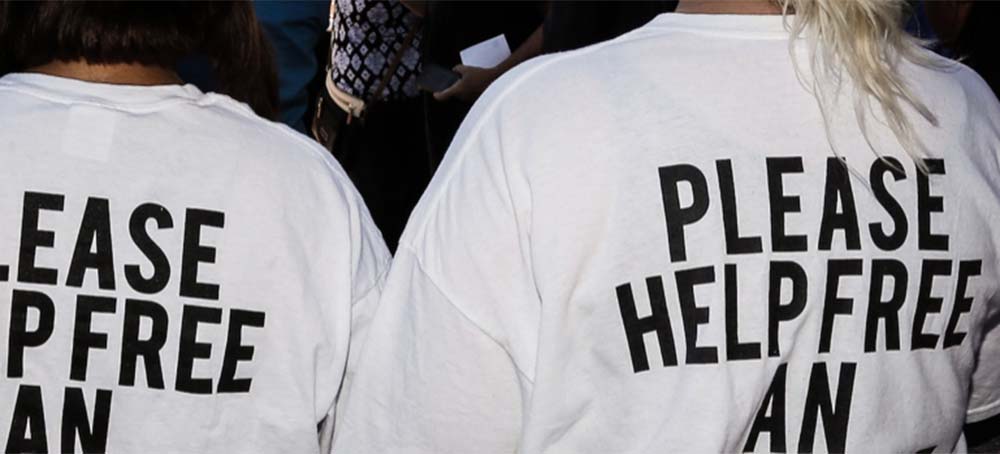

READ MORE  Ericka Glossip-Hodge, left, Richard Glossip’s daughter, and Billie Boyiddle, right, Glossip’s niece, attend a rally protesting his execution in Oklahoma City on Sept. 15, 2015. (photo: Sue Ogrocki/AP)

Ericka Glossip-Hodge, left, Richard Glossip’s daughter, and Billie Boyiddle, right, Glossip’s niece, attend a rally protesting his execution in Oklahoma City on Sept. 15, 2015. (photo: Sue Ogrocki/AP)

An Oklahoma court refused to consider new evidence of Glossip’s innocence. Now the state’s parole board may be his last chance.

Glossip had twice been tried and sentenced to death for the 1997 murder of Barry Van Treese inside Room 102 of a seedy Best Budget Inn that Van Treese owned on the outskirts of Oklahoma City. No physical evidence linked Glossip, the motel’s live-in manager, to the crime. Instead, the case against him was built almost exclusively on the testimony of a 19-year-old maintenance man named Justin Sneed, who admitted to carrying out the killing but said it was all Glossip’s idea. Glossip has steadfastly maintained his innocence.

Over his 30-year career, Berlinger has received widespread acclaim for his work, including on wrongful convictions. When his four-part series “Killing Richard Glossip” was released in 2017, it quickly raised the profile of Glossip’s case. Inspired by The Intercept’s reporting, Berlinger’s series delved into the myriad issues that have plagued Glossip’s conviction and revealed startling new evidence that undercut the state’s theory of the crime.

In his brief to the parole board, Oklahoma Attorney General John O’Connor sidestepped the problems with the state’s case and instead attacked those who would call it into question, including Berlinger. “I took it as desperation on the AG’s part,” Berlinger told The Intercept. “It’s unbelievable that they would go to such lengths to discredit a documentary.”

Over nearly five pages, the AG’s office poked at alleged factual inaccuracies in Berlinger’s series that it deemed “somewhat minor” — allegations Berlinger calls specious — before taking a broad swipe at the documentary as being deliberately slanted in Glossip’s favor. Berlinger said he wasn’t troubled by the fact that the AG attacked his work so much as how he did it.

“It is a documentary hoping to bend the truth in order to convey Glossip’s side as possessing both a legal and moral superiority,” the AG wrote. “Indeed, Berlinger has even acknowledged as much in his other work.” For this proposition, the AG cited a 2021 Irish Times article, claiming that “Berlinger noted that his work ‘allows [him] to play with the nature of truth. Because we live in this post-truth society.’”

But that’s not what Berlinger told the Irish Times.

The filmmaker was talking about a different documentary series — focused on internet sleuths trying to solve what they believed was a murder — that illuminated the dangers of ignoring facts in favor of conjecture.

To make it sound like Berlinger was also talking about the Glossip case, the AG’s office left out the first part of his quote — it was “the series,” Berlinger said, that allowed him to “play with the nature of truth” — and then omitted the following sentence: “I’ve spent a lot of my time doing wrongful conviction cases and being involved at the criminal justice system where circumstantial evidence has led to tragic results. This case shows how, despite all the evidence, people can be so convinced of their own beliefs.”

For Berlinger, the mischaracterization was infuriating and unnerving. “They changed one word, which makes all the difference in the world, and left out the next consecutive sentence, which really changes the whole meaning of things,” he said. If they would do something so brazen and easily disproved to him, what might they do to Glossip?

Berlinger decided to write a letter to the parole board. “If facts are so selectively presented by the state in their clemency brief about one filmmaker’s work,” he wrote, “you must ask yourselves, what other facts have been selectively cherry-picked by the state to tell a convincing but false narrative in Richard Glossip’s case?”

Willful Blindness

Nearly 25 years after he was first accused of plotting his boss’s brutal murder, Glossip is approaching his eighth scheduled execution date in early 2023. On February 16, if Oklahoma finally gets its way, Glossip will be executed by lethal injection at the state penitentiary in McAlester, one week after his 60th birthday.

Yet the evidence pointing to Glossip’s wrongful conviction has only grown stronger over time. His most recent execution date was put on hold by Gov. Kevin Stitt, who granted a stay of execution to allow the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals to consider filings from Glossip’s defense team, which asked the court to hear new evidence in the case. Among the most recent revelations are handwritten letters from Sneed that showed a desire to take back his story about being coerced to kill Van Treese — a narrative that provided the basis for the state’s entire case against Glossip.

The courts have routinely brushed aside such discoveries. With Glossip’s execution date looming, his clemency hearing — tentatively set to take place later this month — may be the last chance for authorities to spare the life of a man whose case has become emblematic of the profound problems with Oklahoma’s death penalty system and capital punishment as a whole. “We now know what really happened — both how the crime was actually committed and how an innocent man got sent to death row,” Glossip’s attorneys argue in their clemency application. Yet prosecutors have continued to insist that their client should die, they write, “without regard to recent developments because two juries found him guilty and sentenced him to death. That is willful blindness.”

Sneed’s version of events was dubious from the start, the product of a coercive interrogation in which homicide detectives repeatedly emphasized their belief that Glossip was involved. Beginning with his confession to police and continuing through each of Glossip’s two trials, where he was the star witness, Sneed couldn’t seem to keep his details straight — not about what led up to the crime, what happened inside Room 102, or who did what after the fact to try to cover it all up. Sneed said Glossip promised to pay him thousands of dollars to kill Van Treese, but the exact amount changed over time.

According to the state, not long before he was murdered, Van Treese discovered that Glossip had been embezzling from the nearly all-cash operation while letting the ratty motel slide into disrepair; he was planning to fire Glossip. The state has argued that in an effort to keep his job, Glossip hatched a plan to kill Van Treese and take over motel operations.

Although Glossip has always maintained that this is preposterous — “I wouldn’t hurt nobody for a job,” he said on the stand in 1998 — he did himself no favors in the immediate aftermath of Van Treese’s murder. When he was first interviewed by police, he failed to tell them about a chilling exchange he says he had with Sneed in the early morning hours of January 7, 1997. Sneed had banged on the wall of Glossip’s apartment at the motel, waking him up; when Glossip opened the door, Sneed told him that a couple of drunks had broken a window — and that he’d killed their boss, Van Treese. Glossip insists that he thought Sneed was joking. But he withheld the information long enough to give people reason to believe he was covering for Sneed. By the time Glossip went to trial, he’d been cast as a sinister puppet master who brainwashed Sneed into committing murder.

For more than two decades, the state has insisted that Sneed was a meek dolt who was powerless to resist Glossip, despite the fact that it was Sneed alone who carried out the bloody attack. Meanwhile, a host of new witnesses have come forward with information disputing the state’s narrative. Residents of the Best Budget Inn said that Sneed was conniving, violent, and often resorted to theft to fund his drug addiction. Men who were incarcerated with Sneed say he boasted about falsely implicating Glossip to avoid facing the death penalty.

One man who spent time with Sneed in the Oklahoma County Jail told Berlinger that Sneed said he and a woman had lured Van Treese into Room 102 to rob him. One of the lead detectives on the case, Bob Bemo, told Berlinger that he doubted Sneed ever meant to kill Van Treese. “He ended up killing Barry. … I don’t know that he intended to, but he did,” Bemo said. “He beat him pretty good.” At one point during his interrogation, Sneed also told the cops that he only meant to incapacitate Van Treese. “I just really meant just to knock him out,” he said. In other words, even Sneed has intimated that the crime was a robbery gone wrong and not a murder for hire.

In 2021, a group of mostly conservative, pro-death penalty Oklahoma state lawmakers asked the governor and the Pardon and Parole Board to conduct an independent investigation into Glossip’s conviction. Neither Stitt nor the board members (the majority of whom are appointed by Stitt) obliged, so in early 2022, the lawmakers sought the help of the law firm Reed Smith LLP, which launched a pro bono, four-month investigation.

A team of attorneys and investigators reviewed more than 12,000 documents and interviewed dozens of witnesses. The result was a bombshell 343-page report that took issue with nearly every aspect of the state’s case against Glossip. Among the revelations: A box of financial records, potentially key to determining if any money was missing from the motel, was destroyed while Glossip’s first conviction was on appeal. By the time he was retried, the evidence was gone. In marking the evidence for destruction, the DA’s office falsely claimed that Glossip’s appeals had been exhausted; oddly, the box was also assigned a new case number, a move that would effectively hide it from anyone searching for the evidence.

Since then, the firm has released additional startling information, including that Sneed considered taking back his story about Glossip. In 2003, a year before Glossip was retried, Sneed wrote to his public defender, Gina Walker, asking, “Do I have the choice of re-canting my testimony at any time during my life, or anything like that.” In 2007, he again reached out to Walker. “There are a lot of things right now that are eating at me,” he wrote. “Some things I need to clean up.” In response, Walker, who has since died, discouraged Sneed from recanting, writing that if he hadn’t testified, he likely would have ended up on death row.

Reed Smith also found evidence that Assistant District Attorney Connie Smothermon worked with Walker during Glossip’s second trial to modify Sneed’s testimony to fit the medical examiner’s finding that Van Treese had puncture wounds to his chest. Although there was a knife found at the scene, at the first trial Sneed denied attacking Van Treese with a knife. At the retrial, Sneed testified for the first time that he had stabbed Van Treese.

Sneed has not responded to The Intercept’s request for an interview.

GOP state Rep. Kevin McDugle, one of the driving forces behind the lawmakers’ efforts to halt Glossip’s execution, is a stalwart supporter of capital punishment. But he is certain that Glossip is innocent. “If we put Richard Glossip to death, I will fight in this state to abolish the death penalty,” McDugle said.

An Insider’s Game

Where McDugle and others are clearly concerned about the integrity of the case against Glossip, the Oklahoma attorney general and five members of the state’s Court of Criminal Appeals remain unmoved.

In the wake of the Reed Smith reports, Glossip’s pro bono defense team, led by attorney Don Knight, filed two additional appeals to the court raising questions about the veracity of the case, asking for an evidentiary hearing, and arguing that Glossip is innocent. The lengthy filings laid out evidence that Glossip’s conviction was plagued by an inadequate police investigation as well as prosecutorial misconduct. The lawyers cried foul over the police destruction of evidence, Smothermon’s plotting with Walker to change Sneed’s testimony, and the failure to turn over Sneed’s ruminations regarding recantation.

In response, O’Connor, the attorney general, suggested that the destruction of evidence was just an honest misunderstanding. The letters Sneed wrote to Walker, meanwhile, only “establish that Sneed feels guilty about petitioner’s fate, possibly because of outside pressure.” In a second filing, O’Connor announced that Sneed had “never discussed recanting, in the legal sense.” (It was unfair, he noted, to assume that Sneed would understand the meaning of the word “recant.”)

The communication between Smothermon and Walker regarding Sneed’s testimony was no big deal, according to the AG, who argued that Sneed’s testimony wasn’t even inconsistent: Sneed first said that he didn’t stab Van Treese and during the second trial said only that he “tried to” stab Van Treese; since the knife didn’t fully penetrate the skin, the two statements weren’t in conflict, the AG wrote.

As for Glossip’s innocence claim, O’Connor argued that none of his evidence was credible and Glossip simply wanted to be spared the death penalty. “Were petitioner innocent, he should not wish to stay in prison,” he wrote. “Instead, he appears to have been slowly gathering evidence to use when his next execution date was set.” The AG argued that this approach was “completely inconsistent” with a claim of innocence.

In two separate opinions, the Court of Criminal Appeals rejected Glossip’s innocence claim and embraced the state’s arguments — including the assertion that Sneed never expressed a desire to recant.

Asked about the AG’s briefs, Knight, Glossip’s lead attorney, sighed. “I would say that they knew the audience that they were writing to,” he said. “They knew what they needed to say to the five judges on the Court of Criminal Appeals to give those five judges enough for them to write the terrible decisions that they wrote. It was like an insider’s game.”

Mostly, Knight is frustrated. He’s spent the last seven years digging into Glossip’s case. And every new revelation brings him back to a central point: The police failed to conduct a thorough investigation into Van Treese’s murder. They never formally interviewed Van Treese’s widow, Donna, for example, and it took nearly a week for them to locate and interview Sneed. They didn’t preserve or interrogate financial documents related to the motel’s operations — so there’s no clear proof that any money was missing from the Oklahoma City property, let alone that Glossip was stealing. Not only was a box of financial records destroyed by the state before Glossip’s second trial, but inexplicably, the police also returned additional records to the Van Treese family shortly after the crime.

Knight has repeatedly written to the Oklahoma County District Attorney’s Office asking for access to records that might provide answers. He has never received a response. “I’ve always just wanted to know what happened here,” Knight said.

Knight also sent a lengthy letter to O’Connor, laying out what detectives did and didn’t do and asking a basic question: Is this enough to support a capital murder conviction? Knight said he’s convinced that Glossip is innocent, but the point of the correspondence wasn’t to harp on that. Instead, he wanted to know if the state was truly satisfied with the murder investigation. “It seems to me that we ought to be able to agree on whether what these cops did was enough or not. … I just can’t imagine any person looking at me straight in the face and saying, ‘Oh, yeah, this is fine,’” he said. “And when you admit that this isn’t enough, the next question becomes, well, what do you do about it now?”

Intimidation Tactics

The Oklahoma Pardon and Parole Board does not usually spare the lives of people facing execution. Although its votes are merely recommendations to the governor, who has the last word, on the rare occasions when the board has called for clemency, the decisions have often been mired in controversy. After board members voted in 2021 to spare the life of Julius Jones — a Black man convicted by a nearly all-white jury who insisted he was innocent — Oklahoma legislators tried to pass a law that would forbid the board from considering innocence claims at clemency hearings for the condemned.

Few politicians have tried to wield power against the board like outgoing Oklahoma County District Attorney David Prater. In 2013, the year before Glossip first applied for clemency, Prater accused the board of violating the state’s Open Meeting Act by keeping a “secret” parole docket and improperly granting early release to people in prison. When the board members refused to resign, he had them arrested on criminal charges, which he dropped the following year. As Oklahoma tried to execute Glossip in 2015, Prater used similar intimidation tactics to try to silence witnesses who came forward. More recently, Prater targeted two board members whom he accused of anti-death penalty bias. As Prater embarked on his final year as DA in early 2022, both members resigned their positions.

Although Prater’s departure from office may give Glossip some reason for optimism, his chances before the board remain fraught with uncertainty. All five current board members will see their terms expire on January 8, at which point at least some will be replaced by new members chosen by the governor. Because a clemency hearing must take place no less than 21 days before a scheduled execution, even those appointed immediately will have little time to acquaint themselves with their new role, let alone the voluminous records in Glossip’s case, prior to his February 16 execution date.

When Glossip last went before the board in October 2014, his case had not yet reached national prominence. Rather than make a vociferous argument for their client’s innocence, his lawyers emphasized the weakness of his conviction. At most, they said, the evidence showed that Glossip was guilty of helping Sneed cover up the murder. They urged the board to consider whether they had “any doubt” as to Sneed’s version of events. “This case is entirely circumstantial except for Justin Sneed’s testimony,” Glossip’s lawyer Kathleen Lord said.

Prosecutors pushed back on the notion that this was a “one-witness case.” They pointed to the single piece of incriminating evidence that has haunted Glossip the most: his failure to tell Oklahoma City police what he knew when they first questioned him. Asked why he wasn’t forthcoming, Glossip repeated what he has told others over the years: “At first I didn’t believe [Sneed] did what he said he did.”

Several members of Van Treese’s family attended the 2014 hearing, including his widow, Donna, who held up a family photo taken a year before her husband’s death. Her voice trembling with emotion, she described how the murder had upended the lives of her children. She reminded the board of something she’d said on the stand at both trials: that Glossip had lied to her too. On January 7, before Van Treese’s body was found, she called Glossip on the phone. He reassured her that things were fine — and that Van Treese had simply gone to the hardware store to get supplies.

Glossip has always insisted that his statements about when he last saw Van Treese were misconstrued. While Donna Van Treese and others said Glossip claimed to have seen him leaving the motel around 7 a.m. on January 7, Glossip said he meant 7 p.m. the night before. Under questioning from a board member at the 2014 clemency hearing, Glossip said he did not remember saying Van Treese had gone to the hardware store.

All five board members voted to deny clemency.

The state’s new clemency brief was filed this summer. The 175-page document adheres closely to what was presented by the attorney general’s office in 2014. It again emphasizes Glossip’s failure to tell the police what he knew, while leaning heavily on witnesses who questioned his behavior after the crime. It doubles down on the notion that Sneed was a wide-eyed simpleton devoid of free will, ignoring those who have come forward over the years to debunk the state’s depiction.

The state’s portrayal of Sneed has always been exaggerated on its face. At Glossip’s 2004 retrial, prosecutors described Sneed as a “Rottweiler puppy” and Glossip as the “dog trainer.” In the latest clemency brief, the attorney general’s effort to paint Sneed as “childlike” verges on the absurd, casting him as so guileless and dependent that his emotions rise and fall dramatically with Glossip’s every move. The same office that has repeatedly weaponized the graphic crime scene photos from Room 102 also manages to downplay Sneed’s violent attack to the point where Van Treese almost comes across as the aggressor — defending himself until Sneed is “able to fight back” and “ultimately able to subdue him with blows from the bat.”

Members of the Van Treese family did not respond to emails about Glossip’s case. According to the attorney general’s office, which resubmitted the family’s 2014 letters to the board, relatives have chosen not to be involved in the clemency hearing this time around.

Of the few things that are new in the state’s clemency brief, none of them have much to do with whether Glossip orchestrated Van Treese’s murder in 1997. To portray Glossip as a con man whose manipulative behavior continues to this day, the attorney general included letters from women who previously supported him but have had a change of heart.

In one affidavit, his ex-wife, who is less than half his age, described how she began a relationship with Glossip after seeing Berlinger’s documentary. “At first, I gave him small amounts of money, then it rapidly grew to higher amounts of money as the relationship progressed,” she wrote. Over time, she said, he would “throw temper tantrums” or threaten to hurt himself if she did not do what he wanted. After they divorced, she concluded he was using her. Another woman, who was not romantically involved with Glossip but also gave him money, wrote that she no longer believes he is innocent. Neither woman said explicitly that they wish Glossip to be executed. Nor did they respond to emails or phone calls from The Intercept.

Of course, Glossip, who has since remarried, does not face execution for mistreating his partner or taking financial advantage of people from his death row cell. Nor do the affidavits suggest he poses a danger to society — something even his second jury failed to find in 2004. Glossip’s prison record shows no signs of violence toward the people who live and work around him. As his clemency petition reminds the board, “Glossip had no prior criminal record and has been a model prisoner for over 25 years.”

For Berlinger’s part, he says he debated whether he should write a letter to the board at all. “Will it matter?” he asked himself. This wasn’t about him, after all. He was just a “grain of sand on the beach” of this complex case, yet the state had decided to focus disproportionate attention on him in a way that was flatly dishonest. That’s what convinced him to write the letter. “I wanted the clemency board to understand that if they did it to me, wouldn’t this be their whole approach to things?”

READ MORE  The Estates at Wellington Green apartment complex in Palm Beach County, Fla. (photo: Saul Martinez/WP)

The Estates at Wellington Green apartment complex in Palm Beach County, Fla. (photo: Saul Martinez/WP)

The company has become one of the nation’s largest landlords in recent years and imposed some daunting rent hikes

Amid a flurry of sales over the past decade, when more than $1 trillion of apartment buildings changed hands, private investors and real estate trusts went on a binge: The proportion of apartments sold to them rose from 44 percent in 2011 to 70 percent in early 2022, according to data and research firm MSCI.

Many of those same firms imposed aggressive rent increases and rode the historic wave of rent hikes to big profits.

Few, however, stood to benefit more than Starwood Capital Group.

A private investment firm led by Florida billionaire Barry Sternlicht, Starwood has been one of the most active acquirers of apartments, and a model for the industry. Over the past seven years, it has amassed a portfolio of more than 115,000 apartments, which by some rankings stands as the nation’s largest such collection.

Private firms rarely disclose specific information about rent hikes, but according to leases reviewed by The Washington Post, prices at some Starwood complexes increased by 30 percent or more annually.

At Starwood’s Estates at Wellington Green in Palm Beach County, Fla., the company raised some rents by as much as 52 percent in 2022; at the Griffin Apartments in Scottsdale, Ariz., it increased them by 35 percent over the same period. At the Cove at Boynton Beach in Florida, it boosted rents on some units by as much as 93 percent in 2022.

At some Starwood apartment complexes intended for low-income tenants and built with government subsidies, the company increased rents by 10 percent. Though the rents on such units are limited by Department of Housing and Urban Development guidelines, the company began charging higher rent soon after the government lifted the limits, even for tenants who were mid-lease.

“Tenants seem capable and willing to pay these rent increases,” Sternlicht said in early 2022 in a call with investors. “I think this is the strongest real estate market I’ve seen in 30 years, 35 years.”

While Starwood says its prices merely reflect market forces and its own rising costs, the growing role of private investors among the nation’s apartment landlords coincides with a historic wave of rent hikes.

In 2021, rent increases were more than double what they had been any previous year, according to the Yardi Matrix Multifamily National Report, with asking rents jumping by 10 percent or more in 26 major metropolitan areas. The increases continued through at least October 2022, when rents were rising about 8 percent annually.

“When they said my rent was going up, I was like, ‘What in the world?’” said Sakeema Rainner, 29, who with her four children rented a government-subsidized, Starwood-owned West Palm Beach apartment where she said the rent jumped about 10 percent in 2022. “They just don’t care.”

Starwood provided some figures to The Post showing that the company raised rents at an average rate of 17 percent in its top 10 markets from January to September 2022. By comparison, overall rents rose in those same markets at a rate of about 12 percent over that period, according to numbers from CoStar, the data firm, shared by Starwood.

The company raised rents more slowly than competitors in 2021, however, according to the figures it provided: It boosted rents by an average of 6 percent while competitors in those markets raised rates by an average of 12 percent.

In a statement, the company said that it has a legal responsibility to reward its investors and that it is “contending with record increases in operating expenses and interest on our mortgages.”

“Starwood is one of the world’s premier real estate investors and owner of apartment properties,” the company said in its statement. “Our reputation is extremely important to us both as an investor and a landlord, and it is something we take very seriously. We would not have been able to grow and maintain our portfolio at this size if we acted differently than any other landlord in this space.”

Tenants

Contrary to Sternlicht’s assessment that tenants are “capable and willing” to pay more, those at several Florida apartment complexes owned by Starwood affiliates said they are struggling to pay the higher rates.

Of 20 people interviewed across four complexes in Palm Beach County, where rent hikes have been particularly sharp, all said they felt a pinch from increases that ranged from $100 to $1,363 more per month. Many were people of modest incomes. Some work two jobs. Among them were home health aides, a pool cleaner, security guards, warehouse employees and restaurant workers.

Veronica Stevens, 38, a worker at a cannabis dispensary, and her 17-year-old daughter share a two-bedroom apartment at the Cove at Boynton Beach, a Starwood property. Their rent is rising from less than $1,500 to $2,070 per month, she said, an increase of about 40 percent. Stevens and her daughter no longer dine out occasionally at Red Lobster or Chili’s as a result, and she is looking for a second job.

Robert Passaretti, 35, a restaurant server, said his rent at Starwood’s Reserve at Ashley Lake in Boynton Beach rose from $1,350 monthly to $2,050. He is thinking about leaving the state.

“It’s crazy,” he said. “All of a sudden I’m living paycheck to paycheck.”

Some families said they were forced into difficult downsizings: Couples with children moved from two-bedroom to one-bedroom apartments even though, as one father said, “we’re tripping over each other.” Another family with three children had a two-bedroom at the Reserve at Ashley Lake. A few months ago, they got a notice that the rent would be rising from $1,600 to $2,000 per month, they said. They moved in with a family member.

“We’re trying to save to get out of the cycle,” said the father, an immigrant from Haiti who sells life insurance, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to maintain his privacy. “The rents are never going to come down. We want to buy a house.”

Even at Starwood’s government-subsidized complexes, managers imposed rent increases of as much as 10 percent, according to leases reviewed by The Post.

Parkside Residences in West Palm Beach, for example, was built in 1996 with a low-interest state loan of $1.9 million and $800,000 in a tax credit subsidy, according to the Shimberg Center at the University of Florida. In return for the government subsidy, the owners of the property are obliged to keep rents below levels set by the federal government. Starwood Real Estate Income Trust bought the 144-unit property in 2020 for nearly $14 million.

On the last day of April 2022, it informed residents that their rents would jump by about 10 percent on June 1 — even if they were in the middle of their lease. A clause in the lease paperwork allowed the company to raise the rent as soon as HUD changed the maximum landlords are allowed to charge.

“They say it’s low-income but it’s so expensive,” said a 66-year-old nursing aide from Jamaica who splits an apartment with a friend from church and spoke on the condition of anonymity for fear of angering property managers. “They don’t care.”

A few doors down, Rainner and her four children share a three-bedroom apartment. They got the notice of the rent hike, too. But worse than the higher price, she said, is what she is paying for. For months, a leaky air conditioner has left large puddles in her living room every day and inundated the carpet in her bedroom. On a visit in October, the bedroom rug squished underfoot like a wet sponge. She said the mold that results causes her kids to cough.

“I call the office and no one answers,” she said.

Other affordable rental complexes owned by Starwood have drawn complaints about maintenance, too, according to local news reports: Tenants of the Nolen Grand complex for older residents in Dallas said the elevator was out of service for three weeks, leaving the frail to navigate flights of stairs with their walkers; tenants at the Courtney Manor apartments near Orange Park, Fla., said they were dealing with uncontrollable mold in their apartments; and tenants at the Santora Villas apartments in Austin complained of broken appliances and other maintenance issues.

Starwood attributed the elevator breakdown at the Nolen Grand to supply chain shortages. It has resolved the problems at Courtney Manor and Santora Villas, which the company said had been present when it purchased those properties. The company declined to comment on individual tenants’ situations.

“Like all property owners, our rental properties experience maintenance issues from time to time,” the company said in a statement. “However, we spend millions every year to correct those issues and are proud of our track record of addressing issues quickly and often times proactively to create a better living environment for our tenants. To suggest our performance in this area is somehow below industry standards by picking a few situations out of our hundreds of thousands of leases we own and manage is an unfair representation of how we conduct ourselves as a property owner.”

Bigger companies, swifter hikes

While rising rents are often justified as a simple matter of supply and demand, they are also the product of countless individual decisions by landlords.

Among the most aggressive landlords, researchers and industry experts say, are large investment groups that buy and sell apartments — especially those that are not trying to build a brand or reputation as an apartment company.

“At large outfits that invest in unbranded apartments, it’s just pure profit maximization,” said Russell James, a professor at Texas Tech’s School of Financial Planning who has studied tenant satisfaction at apartment buildings owned by large ventures. “There is less incentive to do anything other than charge the maximum amount.”

The shorter-term time horizon puts pressure on owners to raise rents because the price of a building often depends upon how much rent money it can produce. The way executives are paid also encourages rent increases: The managers of the investment firms often earn large fees based on profits, and those profits can be fattened with higher rents.

These firms “have an incentive to raise rents as quickly as they can so that they can get the next buyer to pay more,” said Michael Brennan, chairman of the Brennan Investment Group, a real estate firm, and director of the James A. Graaskamp Center for Real Estate at the University of Wisconsin at Madison. Other owners, he said, are “not as maniacally focused on getting the last nickel as quickly as they can.”

Starwood was founded in 1991 by Sternlicht and investment partner Bob Faith to buy up apartment buildings after the savings and loan crisis. Today, its apartment portfolio is ranked as one of the largest in the United States, and it is just one piece of its global real estate empire: Starwood Capital Group manages about $125 billion of investments around the world: hotels, land, offices, industrial parks, apartments and mortgage-backed securities. Starwood managers say they can shift among these varied investments quickly, similar to the way a firm might trade stocks and bonds.

Starwood’s biggest bet on apartments began five years ago, when it created a venture called the Starwood Real Estate Income Trust. After soliciting billions from investors, who were promised “regular, stable cash distributions,” it began assembling a varied real estate portfolio. Among those purchases were dozens of apartment buildings with more than 65,000 units, according to Starwood documents.

How to set rents is one of the questions that divides landlords, particularly for tenants already in the building when rents are rising. When the market price of an apartment surges by 30 percent, it may be easy enough to ask new tenants to pay the higher price — they haven’t moved in yet and can take it or leave it. But should a 30 percent increase be foisted on tenants that have been living there for years?

A Starwood executive weighed the question at an industry event.

“We’re an ownership level that likes to be assertive,” Steve Lamberti, the president of Starwood’s property management division, Highmark Residential, told the audience at an industry webcast that was sponsored by RealPage, a company that provides software to property managers.

“Compassion is a word all of us need to think about,” he said, but he added that landlords should recognize that the prices for existing tenants should “run pretty similar” to what the market is dictating.

“We’re in a position now where occupancy is extremely strong and we are pushing rents,” he said during the webcast.

After The Post viewed the webcast and sought interviews with some of its participants, RealPage removed the webcast from its public website. It later said the webcast was removed at the request of a client.

Investors first

While apartment companies typically view tenants as their customers, the investment firms buying up apartments typically cater first to investors. To tenants, in fact, the investment firms that own their buildings often are invisible: Most interviewed for this story had no idea that their landlord is a Starwood affiliate.

Consider apartment ownership, for example, in Palm Beach County, where private investment groups now own more than half of the 30 most valuable apartment buildings — more than triple the number they owned 20 years ago, according to property assessor records and Post research.

Rents in the county rose by more than 19 percent on lease renewals as of May, according to data from RealPage, a rate that was almost twice the national average. Nowhere in the country did they rise faster.

A representative for Starwood noted that some large public real estate trusts — not just private investment groups — have raised rents by large amounts, too.

Quarterly data shows Starwood raised rents at its South Florida properties by about 21 percent in the 12 months ending in September. While the company declined to say how much its rents rose at individual Palm Beach County properties, The Post was able to determine rent increases from eviction files. Each eviction file in Florida includes a copy of the lease. If an apartment was the site of two evictions, it is possible to see how much the rent had been increased between the two evictions. Some tenants also provided information about how much their rents rose.

Some of the biggest jumps at Starwood properties happened, as might be expected, after an apartment became vacant.

The lease for unit 306 at the Estates at Wellington Green apartments was $1,603 per month in January 2022; five months later, the company was charging $2,444, a 52 percent hike, according to the leases in the court files.

The lease for unit 938 at the Reserve at Ashley Lake apartments cost $1,296 in March 2020; by October 2021, the price had jumped to $1,806, according to the leases.

The hikes on renewed leases were generally smaller, but not always.

One 24-year-old tenant at the Cove at Boynton Beach saw her rent nearly double in May from $1,464 to $2,827 as she shifted to a month-to-month lease, according to court papers. The company filed for her eviction in late June, saying she had failed to pay. In court papers, she wrote that she had paid for her mother’s funeral and was dealing with depression. She asked to be able to stay and asked the judge for an emergency hearing. The eviction had been ordered already. Her request was denied. She declined to comment for this story.

Another tenant, who lives with his daughter in a two-bedroom apartments at the Estates at Wellington Green, said he got a renewal notice that asked for a 24 percent increase — from $1,780 to $2,208. He spoke on the condition of anonymity to not risk angering the company.

Edgar Enrique, a pool cleaner from Guatemala who shares with his wife a one-bedroom at Starwood’s Reserve at Ashley Lake, said his rent jumped from $1,600 to $2,000.

“For me, it’s not good,” Enrique said. “Why does it cost $400 more now?”

READ MORE  People displaced by gang violence in the Port-au-Prince neighbourhood of Cite Soleil take refuge at the Hugo Chavez Square in the Haitian capital, on October 16, 2022. (photo: Ricardo Arduengo/Reuters)

People displaced by gang violence in the Port-au-Prince neighbourhood of Cite Soleil take refuge at the Hugo Chavez Square in the Haitian capital, on October 16, 2022. (photo: Ricardo Arduengo/Reuters)

From gangs to fuel shortages to a cholera outbreak, Haiti is grappling with ongoing setbacks as new year begins.

And over the past 12 months, the situation has largely failed to improve: Haitians have faced a surge in gang attacks and kidnappings, fuel and electricity shortages, a deepening political deadlock and a deadly outbreak of cholera.

“We don’t know what will happen tomorrow,” said Judes Jonathas, senior programme manager at the Mercy Corps humanitarian group. Jonathas spoke to Al Jazeera in October, as gang violence gripped the streets of the Haitian capital Port-au-Prince where he resides.

“It’s as if we’re living minute to minute. We go out, [and] we don’t know if we’ll be coming back,” he said.

As the nation continues to reel from several, overlapping crises, Al Jazeera looks at how the past year in Haiti has unfolded – and what 2023 may have in store.

Increased gang violence

Gang violence is not a new problem in the Caribbean nation, but it has been on the rise, particularly after the July 2021 assassination of President Jovenel Moise worsened months of political instability and created a power vacuum.

Haiti’s de facto leader, Prime Minister Ariel Henry, whom Moise chose for the post just days before he was killed, has faced a crisis of legitimacy, with some Haitian civil society groups urging him to hand power over to an inclusive, transitional government – a demand he has rejected.

Armed gang leaders also have used pressure tactics – including fuel terminal blockades – in an effort to force Henry to resign.

After months of mounting violence, one of the most powerful armed groups – the G9 gang alliance, led by former police officer Jimmy “BBQ” Cherizier – in September imposed another fuel blockade on the main petrol terminal in Port-au-Prince, known as the Varreux Terminal.

The move came after Henry’s government announced plans to end petrol subsidies, setting off public protests among Haitians already struggling with rising living costs.

The weeks-long blockade led to water and electricity shortages across Port-au-Prince, including at hospitals trying to treat cholera patients. Each crisis compounded the other, and a United Nations official said Haiti was staring down a “cholera time bomb” as the instability and violence cut off entire neighbourhoods.

The Haitian authorities regained control of the Varreux Terminal in November, allowing petrol stations to reopen and prompting celebrations in the streets – a rare bright spot amid simmering concerns over the power armed groups wield in the country.

International pressure

As gang violence reached crisis levels in Port-au-Prince in October, Henry – the Haitian prime minister – appealed for an international armed force to be deployed to Haiti to restore order and secure a humanitarian corridor to allow fuel and water deliveries in the capital.

The demand enjoyed the backing of the United Nations, as well as the United States, but set off fresh protests, with many Haitians, including civil society leaders, rejecting the prospect of foreign intervention.

Washington-led efforts to mount “a non-UN mission led by a partner country” to Haiti have stalled since then, as President Joe Biden’s administration so far has failed to get another nation to agree to lead such a force, US media outlets reported.

Instead, the US and its allies, notably Canada, have imposed a series of sanctions against Haitian politicians and others over their alleged support for gangs and other destabilising activities, such as drug trafficking and government corruption.

“Impose sanctions on high-profile individuals involved in corruption and who support and facilitate gang violence in Haiti [and] adopt drastic measures to stop the illicit trafficking of weapons from the US to Haiti,” Velina Elysee Charlier, an activist with anti-corruption group Nou Pap Domi, told the US House Foreign Affairs Committee during a hearing in late September.

Cholera vaccination campaign

Meanwhile, Haitian health officials continue to grapple with the outbreak of cholera.

Caused by drinking water or eating foods contaminated with cholera bacteria, the illness can trigger severe diarrhoea, as well as vomiting, thirst and other symptoms, and can spread rapidly in areas without adequate sewage treatment or clean drinking water.

The first infections in Haiti in more than three years were reported in early October, after a previous outbreak subsided in 2019. More than 17,600 suspected cases have since been detected, according to the latest figures from the country’s public health department (PDF).

A cholera vaccination campaign began on December 19 in some of the most affected areas, after Haiti received the first shipment of more than 1.1 million vaccine doses.

“The arrival of oral vaccines in Haiti is a step in the right direction,” Laure Adrien, director general of Haiti’s Public Health and Population Ministry said on December 12, adding that another 500,000 vaccines were expected to arrive in the coming weeks.

Migration

Over the past year, rising numbers of Haitians have left the country, seeking asylum and opportunity elsewhere in Latin America and the United States.

Thousands have made long journeys on foot, including across a perilous jungle passage between Colombia and Panama known as the Darien Gap, after finding employment and visa opportunities scarce in countries like Chile and Brazil. Others have taken boats in hopes of reaching the coast of Florida.

Haitians have been among the many migrants and refugees turned away by US authorities at the country’s southern border with Mexico in the past year. But in early December, the Biden administration announced that it was extending Temporary Protected Status (TPS) by 18 additional months for Haitian nationals already residing in the US.

The administration cited the conditions in Haiti, “including socioeconomic challenges, political instability, and gang violence and crime”, as the reason for extending TPS, which shields Haitians from deportation and gives them US work permits.

But thousands of Haitian migrants have been repatriated over the past year from Haiti’s neighbour, the Dominican Republic, the only other country on the island of Hispaniola. Top UN officials in November called on Dominican authorities to halt the removals, but they have continued.

Moise killing investigation

More than a year after a gang of armed mercenaries stormed Moise’s Port-au-Prince home and assassinated the Haitian president, the country’s investigation into what happened appears to have stalled.

Dozens of people, including several Colombian nationals, have been arrested as part of the ongoing inquiry into what led to the assassination on July 7, 2021. But the process has been slow-moving. Many questions – and theories – remain as to why Moise was killed.

The US Department of Justice has said a group of about 20 Colombians, as well as some Haitian Americans, participated in the scheme. While the plan initially focused on kidnapping Moise in a purported arrest operation, justice department officials said it “ultimately resulted in a plot to kill the president”.

The US has charged three men for their alleged roles in the assassination.

Calls for support

Now, as 2023 begins, international organisations have called for more support to help Haiti respond to the crises it faces.

“Things are now at a breaking point. This crisis will not pass – it needs renewed and robust humanitarian assistance,” Jean-Martin Bauer, the Haiti director of the UN World Food Programme, said on December 19.

Bauer said that more than half of the Haitian population – approximately 4.7 million people – face a food crisis. That includes 19,000 residents of the violence-plagued Port-au-Prince neighbourhood of Cite Soleil, who are suffering from a “catastrophic” level of food insecurity.

“What Haiti is experiencing now is not merely a bout of instability that will subside as part of some regular cycle the world is inured to. Haiti is experiencing a crisis on an unprecedented scale that can only worsen – unless we act fast and with greater urgency from us all,” he said.

READ MORE  The Havasupai falls inside the Grand Canyon in Arizona are naturally occurring. (photo: KiraVolkov/Getty Images/iStockphoto)

The Havasupai falls inside the Grand Canyon in Arizona are naturally occurring. (photo: KiraVolkov/Getty Images/iStockphoto)

Biden Declares Arizona Floods a Federal Disaster for Havasupai Tribe

Maya Yang, Guardian UK

Yang writes: "The White House has made a federal disaster declaration for the Havasupai Native American tribe that mainly lives deep inside the Grand Canyon in Arizona, as the community prepares to reopen tourist access to its famous turquoise waterfalls next month."

The declaration provides funds and federal assistance for emergency and permanent infrastructure

Last October, the village experienced drastic flooding which damaged extensive parts of the reservation.

The floods “destroyed several bridges and trails that are needed not only for our tourists, but for the everyday movement of goods and services into the Supai Village”, the tribe said.

The Havasupai is now readying itself to receive tourists again from 1 February on its reservation, which sits nine miles down narrow trails between spectacular red rock cliffs deep within the Grand Canyon in northern Arizona. Tourists must apply for permits to enter the reservation.

It is the first time that tourists have been allowed to return to the reservation not only since the flooding, but in almost three years, since tourism was closed off early in 2020 when the coronavirus pandemic spread across the US. The canyon community has very limited health care resources on site.

The tribe is one of North America’s smallest and is the only one based inside the canyon, where the community has lived for more than 800 years, despite being driven off much of its original, much wider, territory by armed settlers in the 19th century.

On 31 December the White House announced that Joe Biden had approved a disaster declaration for the Havasupai. According to the Federal Emergency Management Agency (Fema), such a declaration provides a wide range of federal assistance programs for individuals and public infrastructure, including funds for emergency and permanent work.

The tribe grows crops and keeps farm animals on a thin ribbon of land inside the canyon, alongside the naturally occurring, vividly hued streams and falls. Havasupai means the people of the blue-green water.

The tribe issued a statement last month, reflecting on last fall’s flooding, saying: “This has been a trying experience for all involved … However, there are many positive things as a result. While you may see downed trees on the trails where the flood crashed through, you will also see flourishing flora and fauna and new waterfall flows.”

The White House noted that: “Federal funding is available to the Havasupai tribe and certain private non-profit organizations on a cost-sharing basis for emergency work and the repair or replacement of facilities damaged by the flooding,” the statement continued.

In December, the tribe noted that it had been in a dispute with the third-party tourism operator it had normally worked with and had switched to another operator in preparation of the 2023 tourism season.

Last month, the tribe also reported fresh uranium mining activity in the Grand Canyon region where the tribe’s water source originates, which it has long claimed is an existential threat.

“It is time to permanently ban uranium mining – not only to preserve the Havasupai tribe’s cultural identity and our existence as the Havasupai people but to protect the Grand Canyon for generations to come,” the tribal chairman, Thomas Siyuja Sr, said in a statement reported by Native News Online. “With recent activity observed inside the mine fence, it is clear that the mining company is making plans to begin its operations.”

The legacy of uranium mining has long threatened Native American communities, including the Havasupai tribe. From 1944 to 1986, close to 30m tons of uranium ore were extracted from neighboring Navajo lands. During the cold war, companies extracted millions of tons of uranium in those territories to meet the demands for nuclear weapons, causing environmental blight.

READ MORE

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.