Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

We may never know who turned on Trump, but Jared Kushner and Ivanka Trump certainly make the most sense when it comes to possible informants

Milk. Bagged salad. Giving Donald Trump the benefit of the doubt. These are all things which don’t tend to age particularly well. See, for an example of that last item, a segment from Fox News on Thursday where Dana Perino, the former George W Bush White House press secretary, was up in arms over the FBI raiding Donald Trump’s Mar-a-Lago property. “Short of the nuclear codes being written on these documents, locked behind closed doors, I don’t understand how a document could warrant this kind of … warrant,” Perino scoffed. A commentator on CNN expressed the same opinion: “Anything short of finding the nuclear codes at Mar-a-Lago is going to hugely backfire on the Biden administration.”

As I’m sure I don’t need to tell you, it appears that FBI agents were looking for secret documents about nuclear weapons when they searched Mar-a-Lago on Monday. There were always suspicions that Trump might try to smuggle some silver out of the White House when he left – maybe pilfer a piece of art or two – but I’m not sure anybody was quite expecting that he would take classified nuclear documents to his beach house. Trump, by the way, is denying the claims, which were first reported by the Washington Post. “Nuclear weapons is a hoax, just like Russia, Russia, Russia was a hoax,” Trump wrote on his Truth Social platform on Friday.

Details of the Mar-a-Lago raid are still emerging and, as it stands, there are still a lot more questions than answers. One of the biggest questions being: who snitched? Trump’s former personal lawyer and fixer Michael Cohen reckons it was definitely a member of the former president’s circle. Speaking to Insider on Thursday, Cohen said that he “would not be surprised to find out [the informant] is Jared or one of his children … Who else would know about the existence of a safe and the specific contents kept inside?”

Jared Kushner and Ivanka Trump certainly make the most sense when it comes to possible informants. The couple controversially had top-secret security clearance when they were advising Trump in the White House and were very close to the former president’s affairs. The PR-savvy pair have also been distancing themselves from Trump ever since he left the White House. Ivanka Trump has very publicly rejected his big lie that the election was stolen, telling the congressional panel investigating the insurrection at the US Capitol on 6 January 2021 that she doesn’t believe her father’s false claims. Most recently the tabloids have been full of anonymous reports about how Ivanka Trump is trying to stop Trump from running for a second term. Javanka are very clearly out to protect themselves, even if it means handing dear old dad into the feds.

We may never know who turned on Trump, of course. The only thing we can say for sure at this point is that Trump has had a remarkably bad week. Being suspected of stealing nuclear documents would be bad enough by itself, but the former president is facing legal trouble from a number of different directions. After being raided by the FBI on Monday, Trump travelled to New York on Wednesday to be deposed in the state attorney general’s investigation into his business dealings. Can he come back from all of this? Tune into next week’s episode of You Can’t Make This Stuff Up, to see!

Rudy Giuliani. (photo: Drew Angerer/Getty Images)

Rudy Giuliani. (photo: Drew Angerer/Getty Images)

The former Trump attorney’s lies about the 2020 election are catching up with him

Fulton County District Attorney Fani Willis has since Feb. 2021 been investigating Donald Trump’s efforts to overturn the 2020 election results in the state. Giuliani was at the forefront of the former president’s efforts to overturn the results nationwide. Reversing the results in Georgia, which President Biden narrowly won, was a key part of this effort, and in Dec. 2020 Giuliani appeared before legislative panels in the state, pushing several unfounded conspiracy theories about the election having been rigged.

One such conspiracy theory was that Shaye Moss, a Fulton County election worker, worked with her mother to give the state to Biden. Moss testified before the Jan. 6 committee in June about the harassment she’s received since Giuliani and others falsely tried to implicate her in a scheme to rig the election. “It has turned my life upside down.” she said. “I don’t want anyone knowing my name […] I just don’t do nothing anymore, I don’t want to go anywhere. I second guess everything that I do. It’s affected my life in a major way, in every way. All because of lies.”

Moss also debunked several of Giuliani’s claims, including that she and her mother exchanged a USB drive full of illegal votes for Biden. Moss clarified that she was actually passing her mother a ginger mint.

Giuliani was subpoenaed last month in the grand jury investigation along with other Trump allies allegedly involved in the effort to overturn the results in Georgia — including Linsdey Graham, who on Monday was ordered to testify. Giuliani moved to testify remotely but was ordered by a judge last week to appear in person. He is expected to do so this week.

RUDY GHOULiani was suspended from practicing LAW because he LIED to a court and acknowledged that THERE WAS NO PROOF OF ELECTION FRAUD.

Let's remember GHOULiani held a media event at FOUR SEASONS....TOTAL LANDSCAPING that epitoizes RUDY:

Four Seasons Total Landscaping Local Ad

https://youtu.be/VAyh2xPrFvo

Rudy Giuliani’s Bogus Election Fraud Claims

https://www.factcheck.org/2021/06/rudy-giulianis-bogus-election-fraud-claims/

Rudy Giuliani Melts Down On Fox And Admits He Has No Election Fraud Evidence

https://www.politicususa.com/2020/11/15/rudy-giuliani-election-fraud-evidence-guess.html

A top Georgia election official says Rudy Giuliani 'lied' about election fraud by presenting a deceptively edited video as evidence

https://www.businessinsider.com/election-official-says-giuliani-lied-about-election-fraud-2021-1?op=1

Rudy Giuliani admits his election fraud "evidence" came from social media posts

https://www.msn.com/en-us/news/politics/rudy-giuliani-openly-admits-his-election-fraud-evidence-came-from-social-media-posts/ar-AAP4DNB

Judge cancels fraud evidence hearing after Rudy Giuliani admits "this is not a fraud case" in court

https://www.salon.com/2020/11/18/judge-cancels-fraud-evidence-hearing-after-rudy-giuliani-admits-this-is-not-a-fraud-case-in-court_partner/

There's a great deal of information available about RUDY if you look....just another LOSER tRUMPER!

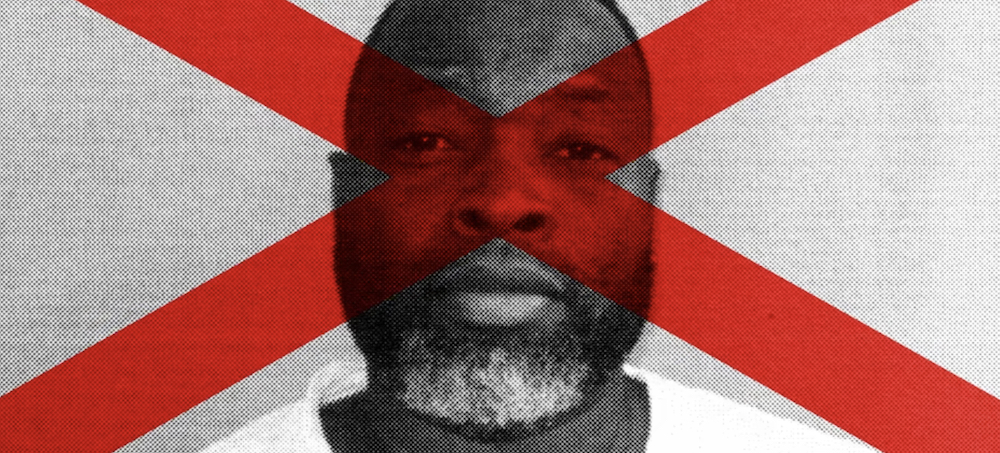

Joe Nathan James. (image: The Atlantic)

Joe Nathan James. (image: The Atlantic)

What did the state of Alabama do to Joe Nathan James in the three hours before his execution?

A little over a week ago, James’s body lay on a bloody shroud draped over an exam table in an Alabama morgue scarcely large enough to accommodate the three men studying the corpse. He had been dead for several days, but there was still time to discover what exactly had happened to him during the roughly three-hour period it took to—in the Department of Corrections’ telling—establish access to a vein so an execution team could deliver the lethal injection of drugs that would kill him. Despite the long delay and an unnaturally short execution, the Department of Corrections had assured media witnesses gathered to observe James’s death that “nothing out of the ordinary” had happened in the course of killing the 50-year-old. It was suspicion of that claim that led to this private autopsy.

By the time I arrived at the morgue where Joel Zivot, an associate professor of anesthesiology and surgery at Emory University and a lethal-injection opponent, had agreed to join a local independent pathologist named Boris Datnow and his assistant, Jay Glass, James’s body had undergone days of postmortem swelling in cool storage. Datnow would later caution me about the difficulty of our inquiry—the edema had diminished our chances of locating punctures left by needles during the execution—though my initial impression of James was of someone whose hands and wrists had been burst by needles, in every place one can bend or flex. That and the carnage farther up one arm told a radically different tale than the narrative offered by the Alabama Department of Corrections, even to the naked eye. Something terrible had been done to James while he was strapped to a gurney behind closed doors without so much as a lawyer present to protest his treatment or an advocate to observe it, yet the state had insisted that nothing unusual had taken place. Approached for comment about the allegations contained in this article, Department of Corrections officials declined to speak with me.

Obdurate disregard for genuine inquiries seems to be the state’s disposition where capital punishment is concerned. In the months prior to James’s execution, Faith Hall’s brother Helvetius and her two daughters, Terrlyn and Toni, lobbied Governor Kay Ivey to spare the man’s life, repeatedly stating that they had forgiven James and had no desire to see him killed. (The Halls, like James, are Black.) Nevertheless, the execution, scheduled for 6 p.m., went ahead unhindered, with Ivey explaining her office’s disregard for the victim’s family’s wishes as a matter of principle.

When members of the media who had been selected to witness James’s execution arrived for their transport to William C. Holman Correctional Facility’s death chamber, two female journalists, the Associated Press’s Kim Chandler and AL.com’s Ivana Hrynkiw, were subjected to dress-code checks by prison staff, who demanded that Hrynkiw change from a skirt into a borrowed pair of men’s fishing waders and sneakers before allowing her to proceed as a witness. By the time everyone was shod and apparreled to the DOC’s specifications and loaded onto prison transport vans, it was 6:33 p.m. (I had contacted the agency about applying to witness James’s execution, but had been ignored.)

And then, media witnesses reported, they waited—for hours. Prisoners on Holman’s death row held up signs—a captive message from a captive audience—stating that the victim’s family didn’t want James dead, that this was a murder. Time passed, then more: Finally, around 9 o’clock, roughly three hours after the scheduled time of execution, media witnesses were led into the execution chamber.

I have witnessed two executions, and in both cases the men were alert and responsive to corrections staff in the moments prior to lethal injection. After all, multidrug cocktails including paralytics and sedatives only begin to affect a person’s consciousness after administration. Before the injections begin, the men I’ve seen die have spoken at least briefly of love and regret. But James neither responded to his death warrant nor gave any last words—not even a refusal to offer a final statement, per Kim Chandler. In fact, witnesses, including Chandler and Hrynkiw, reported that James’s eyes stayed closed during the entire procedure, flickering only in his death throes, and that he remained unresponsive from beginning to end. His death warrant was read at 9:03 p.m., the lethal drugs began to flow at 9:04, and he was declared dead, finally, at 9:27.

What happened to James during the three-hour interval between his scheduled execution and his time of death, and why was he apparently unconscious in the execution chamber? The Alabama DOC gave the gathered reporters no explanation for the long delay, or for his strange demeanor in the chamber. Pressed for an explanation by journalists on the scene that night, John Hamm, the corrections department commissioner, said, in somewhat scattered fashion, that he couldn’t “overemphasize this process. We’re carrying out the ultimate punishment, the execution of an inmate. And we have protocols and we’re very deliberate in our process, and making sure everything goes according to plan. So if that takes a few minutes or a few hours, that’s what we do.”

Subsequent official statements only confused matters further. For instance, DOC spokesperson Kelly Betts wrote in an email to members of the media that “ADOC’s execution team strictly followed the established protocol. The protocol states that if the veins are such that intravenous access cannot be provided, the team will perform a central line procedure. Fortunately, this was not necessary and with adequate time, intravenous access was established.” Eventually, the DOC conceded that it could not confirm whether James had been “fully conscious” during the lethal-injection procedure, though it assured journalists that he had not been sedated.

Aside from the DOC, nobody seemed especially satisfied with that account of events. Jim Ransom, the last of many defense attorneys to represent James, was especially disturbed when he heard that his client hadn’t responded to the warden’s prompt to offer his last words. “That sent up red flags. It didn’t ring true,” Ransom told me the night of the autopsy. “Joe always had something to say. Joe would’ve said no,” Ransom insisted, if he didn’t have anything to say: “That’s Joe.” (Ransom told me that James had asked that he not be present the night of the execution.) But somehow during the three-and-a-half-hour delay, James had transformed from a devout Muslim and dedicated jailhouse lawyer who, in Ransom’s telling, “wanted to fight ’em to the very last minute” into someone mute and absent, with neither an apology for his victim’s family nor an utterance of gratitude for their efforts to save his life.

I spoke with Helvetius, Hall’s brother, in the days after the autopsy. He told me that he wasn’t especially shocked by James’s silence, but that he was appalled by the state’s. In the weeks leading up to the execution, Helvetius said, “Nobody called us, nobody reached out to us, nobody—nobody—got in touch with us.” Toni, Faith’s youngest daughter, who was a toddler when her mother was killed, told me she had repeatedly asked the district attorney’s office to let her speak with James prior to his execution, only to be refused. “There could have been a conversation to heal a little 3-year-old’s heart,” she said, pausing to swallow tears. But nobody in any position of power, aside from Alabama State Representative Juandalynn Givan, who lobbied the state on behalf of the family, seemed particularly interested in what would bring her or her family peace, much less a sense of closure. They simply wanted James dead.

A clinician of 27 years, Joel Zivot worked mainly in intensive-care units and operating rooms before investigating the disappearance of sodium thiopental (an erstwhile anesthetic recruited into lethal-injection cocktails) from the American market circa 2010, due to capital punishment. Zivot’s curiosity about the vanishing of a good drug eventually led him to research lethal-injection protocols, at which point he became a vocal critic of the death penalty’s use of medical means for lethal ends. Now, having published papers on the bioethical hazards of physician participation in lethal injection and having testified about his research into the end-of-life suffering evinced by the autopsy reports of executed prisoners, Zivot has become a familiar presence in legal challenges to executions nationwide. Friendships across the anti-capital-punishment advocacy domain made him especially well placed to set up the independent autopsy of Joe James. Within two days of the execution, Zivot had heard rumors about errors, and he began working in earnest to probe the man’s death.

Before any exam could take place, James’s next of kin would have to agree. I connected Zivot with Ransom to reach out to James’s family. “I had my suspicions about the time lapse,” Ransom explained, “and I feel like the state needs to be held accountable when they mess up.” With that in mind, he called Hakim James, one of Joe Nathan James’s brothers, whose mother had charged him with handling his brother’s final affairs, and asked if he would agree to submit James’s body to an independent autopsy.

Hakim considered, then gave his consent. “I felt it needed to be done,” he told me later, even though it came at the end of an already protracted, taxing process. “I felt that it was important.”

Then there was the matter of locating an independent pathologist willing to take on the case, and finding the money to pay them. I suggested that Zivot reach out to Reprieve, a nonprofit civil-rights organization made up of lawyers, advocates, and investigators who defend the rights of people facing extreme abuses. Maya Foa, an executive director at Reprieve USdirector, agreed that an independent autopsy ought to happen—quickly.

“Lethal injection was developed to mask the very torture it inflicts,” she explained over text message, “and when a prisoner is executed in secret, the only person who can tell the world what really happened is dead. We’ve seen time and again states suppressing or delaying autopsy results following executions that appear to have gone disastrously wrong. Autopsies help tell the story that the body leaves behind.” Reprieve agreed to fund the autopsy through its newly launched Forensic Justice Initiative. By Tuesday morning, Zivot was en route to Alabama from Atlanta and I was making my way from my home in New England; we met in Birmingham, and then went together to the funeral home where the autopsy was to be performed.

The human body opened along “a standard Y-incision”—across the breast and down the center of the abdomen—was unmistakably that of Joe Nathan James. His head was encased in a clear plastic bag, laid to one side, and his face was slack and ashen. The state of Alabama had already wrought its work twice upon James: First in the execution itself, and then again in the autopsy carried out at the Mobile medical examiner’s office immediately after, the findings of which would not be made available for a minimum of 90 days, in the optimistic estimation of local capital defenders. And while the array of viscera and the accordion-style slicing of organs was appalling in its bloody gratuitousness—James had been, according to Datnow, a generally healthy man, prior to his execution—it was the story his flesh told about his lengthy and painful death that lent the scene its awful vertigo. In a little green storefront funeral parlor in Birmingham lay the visual record of everything the government can do to you, provided that you, like James in his final hours, have no counsel present, no wealth to your name, and no contact with the outside world.

James, it appeared, had suffered a long death. The state seems to have attempted to insert IV catheters into each of his hands just above the knuckles, resulting in broad smears of violet bruising. Then it looked as though the execution team had tried again, forcing needles into each of his wrists, with the same bleeding beneath the skin and the same indigo mottling around the puncture wounds. On the inside of James’s left arm, another puncture site, another pool of deep bruising, and then, a scant distance above, a strange, jagged incision, at James’s inner elbow. The laceration met another cut at an obtuse angle. That longer, narrower slice was part of a parallel pair, which matched a fainter, shallower set of parallel cuts. Underneath the mutilated portion of James’s arm was what appeared to be yet another puncture—a noticeable crimson pinprick in the center of a radiating blue-green bruise. Other, less clear marks littered his arm as well.

Mark Edgar, a pathologist at the Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology at the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Florida, reviewed my photos from James’s autopsy and concluded in an email that all of the wounds on James’s arm happened before death, judging by the redness along the edges of the wounds. One among them—the deeper, wider cut at James’s elbow—suggested, in Edgar’s view, “that the inmate moved suddenly while the central cut was being placed, possibly in an attempt to access a vein.”

Zivot, upon examining the body, agreed that the incision carved into James’s arm was most likely made in the death chamber, in an attempt to expose a vein that execution staff could see. The medical term for the procedure is cutdown, and its aftermath dismayed Zivot. “The use of a cutdown in this situation is a stark departure from what would be done in a medical setting,” he explained in an email. “I can’t tell if local anesthetic was first infused into the skin, as slicing deep into the skin with a sharp surgical blade in an awake person without local anesthesia would be extremely painful. In a medical setting, ultrasound has virtually eliminated the need for a cutdown, and the fact that a cutdown was utilized here is further evidence that the IV team was unqualified for the task in a most dramatic way.”

The absence of a local anesthetic during a cutdown, however, could explain two other unusual features of James’s execution: the shallow lacerations lining his arm, and the fact that he was evidently unresponsive during the entire lethal-injection procedure witnessed by the media.

Edgar observed that the “roughly parallel” incisions did “not appear to be part of any procedure,” but were “more consistent with trauma in my opinion, presumably incurred during a struggle that took place during the prolonged efforts to gain access to a vein.” If James had struggled profoundly enough to tear his own flesh with his restraints, that in itself may have prevented IV access. In that case, members of the execution team may have resorted to sedating James.

“I also see several puncture marks not in the anatomical vicinity of a known vein,” Zivot wrote in his assessment. “It is possible that this just represents gross incompetence, or some, or one, or more of these punctures were actually intramuscular injections. An intramuscular injection in this setting would only be used to deliver a sedating medication.”

With roughly one minute elapsing between the reading of James’s death warrant and the rush of poison into his veins, per witness accounts, it scarcely seems that anyone involved in his execution expected him to offer last words. Further, the DOC’s own admission that it cannot confirm James’s consciousness during the procedure raises an obvious question: Why? James had been alone in DOC custody for the past three hours, presumably undergoing repeated, torturous, abortive efforts to gain lethal access to one of his veins. If something had happened to James during that period that affected his consciousness, only DOC staff would know, and the agency’s complete failure to account for the last hours of James’s life or the awful suffering inflicted upon him before his death is ghastly, the sort of catastrophic, pseudo-medicinal brutality of our recent past that mainly flourishes behind closed doors.

Alabama had good reason to think it would never be held to account for what happened to James: He was, at the time of his death, entirely alone, having sought no attendees for his death. In fact, Ransom told me, James had been representing himself in a couple of pending matters before federal courts at the time of his execution, meaning that if he was indeed sedated at some point, what slim semblance of legal counsel he had—his own wits and abilities—was extinguished before his execution.

The thought troubled Ransom. If he had been present, he told me, he would have intervened on James’s behalf. There would have been precedent for that kind of intercession: As recently as 2018, Alabama was forced to halt the execution of Doyle Hamm after execution staff punctured his body at least 11 times in his ankles, legs, and groin, apparently even piercing his bladder over a three-hour period. Hamm’s attorney, Bernard Harcourt, was there that evening, demanding an explanation for the long delay and preparing a legal offensive for the morning. Hamm’s case has since become emblematic of the grotesque reality of lethal injection, compared with its putatively sterile, professional public-facing aesthetics. Lethal injections largely happen, quite literally, behind a curtain; what observers do see looks vaguely surgical; what they don’t looks like a war crime.

“The details of the torture inflicted on Joe James are tragic, but unfortunately no surprise to anyone who has had a client executed in Alabama with lethal injection,” John Palombi, an assistant federal defender, told me in an email. “Adding to the torture is the refusal of the Alabama Department of Corrections to admit or accurately discuss the issues with Mr. James’ execution … There should be an immediate moratorium on all executions in the state of Alabama until a thorough investigation of Alabama’s execution process, done by people outside the Department of Corrections, is complete.”

Megan McCracken, a lawyer based in Philadelphia with expertise in execution methods, told me in an email that, “It is only because of the total lack of transparency surrounding executions in Alabama that the DOC was able to spend such a long time on failed IV access attempts. If this process had been performed openly in front of witnesses, such that anyone outside the DOC knew what was happening at the time, the attempts likely would have been stopped. It is hard to imagine that the courts would countenance this kind of harrowing procedure, but when DOCs can shield their actions and make them invisible to the public, there is no accountability.”

Deborah Denno, a law professor and the founding director of the Neuroscience and Law Center at Fordham Law School, emphasized to me that James’s case is only the latest in a long sequence of botched executions that challenge the constitutionality of lethal injection on Eighth Amendment grounds. “From the very first lethal injection execution to the last—that of Joe Nathan James—the method is predictably disastrous, all the more so in the last dozen years given the lack of availability of drugs,” Denno wrote to me in an email. “James’s execution not only resembles the execution botches of the 1980s, it is even more egregious given the excessive lack of care and prison officials’ indifference to the safeguards of the execution process.”

Which is not to say that the state of Alabama will pay any particular heed to this investigation or its aftermath. There is no lobby for dead men. Execution states—24 remain—are, more and more, retreating into secrecy and elaborate privacy laws to hide their execution means and methods. Some states, like Alabama, simply ignore press inquiries into their executions or, as in this case, subject journalists to inexplicable delays and bland, unconvincing evasions. It appears that the state thought no one would catch it at what it was doing, and in most cases it would be correct; that alone is haunting. That it may haunt Faith Hall’s family evidently mattered not a jot to the state of Alabama.

The Halls, having fought for James’s life, were dismayed and outraged by the news of his torturous death. In Helvetius’s view, he said, Governor Ivey “was wrong for not contacting the victim’s family in any fashion, and she was wrong with her statement that Faith Hall got justice. This is not what she would have wanted. And we deserve an apology for that.”

Toni Hall agreed, as did State Representative Givan.

The family “simply wanted to be heard,” Givan told me. “They wanted an acknowledgment that they were victims and that their voices were listened to and that their concerns were weighed seriously. And I wonder: If they had been white, Anglo-Saxon Americans, would the governor or Attorney General Steve Marshall have at least returned their phone calls?”

Givan reflected that the entire sequence of events had been a grand indignity visited upon a family struggling to heal for more than 25 years, which concluded with the state’s utter indifference to their wishes and with James, the object of their attempted mercy, evidently too incapacitated on his deathbed to offer the barest apology.

But there is reason to believe that he intended to.

I spoke with two prisoners on Holman’s death row who had known James, spent some of those long years with him, seen him age and change into an older, different man—a committed Muslim who prayed regularly and devoted much of his time to studiously pursuing his own defense, not just for his own purposes, but for the sake of his friends on the row.

One of them told me that James had planned three items for his final words: To apologize to his mother and daughters, to apologize to the Hall family, and to pray the shahada, the Muslim profession of faith. He felt grateful for the family’s advocacy on his behalf, even startled by it, by the abrupt unilaterality of forgiveness. But he trusted it, and he appreciated it, and he needed it.

James still hadn’t chosen the exact words he meant to say, the second prisoner told me. The mind revolts at such closely considered finalities, and James had more reason than most to hope for mercy. Somewhere deep inside, he believed the Halls’ forgiveness had saved him.

Brittney Griner. (photo: CNN)

Brittney Griner. (photo: CNN)

If Brittney Griner weren’t a Black woman, her story would have looked very different

Griner is one of the most accomplished and impressive female basketball players in the world. After an astonishing college career and becoming a number one WNBA draft pick, the ESPY award-winning, all-American champion who has also helped secure multiple Olympic gold medals for team USA is widely thought of as one of the best to ever play the game. And yet, in the early days of her arrest, there was near radio silence about her unfair detention.

To put this into perspective, there is no universe in which an arrest involving Michael Phelps, Roger Federer or Tom Brady would not immediately make headline news across the globe. It simply would not play out that way.

But regardless of her elite status, the US had a duty to fight for Griner and her freedom, and failed woefully to meet that duty. Trevor Reed – a former US marine who himself was recently freed from a Russian prison after the government negotiated a prisoner exchange on his behalf – said it best: “In my opinion, the White House has the ability to get them out extremely fast, and they clearly have chosen not to do that. So no, in my opinion, they’re not doing enough.”

And while it’s clear that the US government didn’t fight nearly hard enough for her in those crucial early days, the ways that America failed Griner go well beyond the fact that she’s staring down nearly a decade behind bars.

The first of those failures involves why she was in Russia to begin with. The WNBA champion was entering the country to play with the Russian Premier League, as she’s done during every offseason for the last several years. But it’s not just for fun. WNBA salaries are abysmally low, and there are only 14 players in the entire league who earn $200,000 or more. Griner is one of them, clocking in at an average of $221,515 a year in her latest contract. Comparatively, peers like Kevin Durant and LeBron James averaged $48,554,830 and $42,827,766 respectively. This disparity means that female players – even the most seasoned and talented like Griner – are often forced to play in foreign leagues during their WNBA downtime in order to supplement their income.

Basketball aside, though, it’s impossible to ignore the tragic irony that surrounds Griner’s situation. She is stuck in a diplomatic quagmire between two countries that hate each other, but also hate everything she is; Black, queer and female.

As her agent Lindsay Colas said in a Thursday release following news of her sentence, “Today’s sentencing of Brittney Griner was severe by Russian legal standards and goes to prove what we have known all along, that Brittney is being used as a political pawn.”

Colas’s qualification of Griner as a political pawn is right on the money, but it would be remiss not to point out who Griner is, and why she made such an easy target. Griner is a gay Black woman caught between two countries that each have their own deep, longstanding cultures of anti-Blackness and hostility toward LGBTQ+ people.

And while it’s left to be seen whether or not she will spend the next near decade in Russian jail, all hope isn’t lost. Former UN ambassador Bill Richardson, who has been working alongside Griner’s team, says he is optimistic about a potential prisoner exchange that would free Griner.

Still, no matter how this goes, the damage will already have been done. Griner will have already languished in detention for months, an event that she will no doubt need time to heal and recover from. And when we look back on what happened when a Black, queer woman who is one of the country’s most important sports figures was unjustly imprisoned abroad, this will always be America’s legacy.

Voters at a polling precinct. (photo: Jessica McGowan/Getty Images)

Voters at a polling precinct. (photo: Jessica McGowan/Getty Images)

A state police inquiry found evidence of an election fraud conspiracy that has echoes elsewhere in the country

The election had gone smoothly, she said, just as others had that she had overseen for 17 years as the Rutland Charter Township clerk in rural western Michigan. But now a sheriff’s deputy and investigator were in her office, asking her about her township’s three vote tabulators, suggesting that they somehow had been programmed with a microchip to shift votes from Donald Trump to Joe Biden and asking her to hand one over for inspection.

“What the heck is going on?” she recalled thinking. The surprise visit may have been an “out-of-the-blue thing,” as Hawthorne described it, but it was one element of a much broader effort by figures who deny the outcome of the 2020 vote to access voting machines in a bid to prove fraud that experts say does not exist.

In states across the country, including Colorado, Pennsylvania and Georgia, attempts to inappropriately access voting machines have spurred investigations. They have also sparked concern among election authorities that, while voting systems are broadly secure, breaches by those looking for evidence of fraud could themselves compromise the integrity of the process and undermine confidence in the vote.

In Michigan, the efforts to access the machines jumped into public view this month when the state attorney general, Dana Nessel (D), requested a special prosecutor be assigned to look into a group that includes her likely Republican opponent, Matthew DePerno.

The expected Republican nominee, Nessel’s office wrote in a petition filed Aug. 5 based on the findings of a state police investigation, was “one of the prime instigators” of a conspiracy to persuade Michigan clerks to allow unauthorized access to voting machines. Others involved, according to the filing, included a state representative and Barry County Sheriff Dar Leaf.

Although Hawthorne rebuffed the request by investigators to examine one of her machines, a clerk in nearby Irving Township handed one over to the pair despite state and federal laws that limit who can access them. About 150 miles north of Hawthorne’s township, three clerks in two other Michigan counties turned over voting machines and other equipment to third parties, public records show.

The petition says tabulators were taken to hotel rooms and Airbnb rentals in Oakland County, where a group of four men “broke into” the tabulators and performed “tests” on them. The petition says that DePerno was present in a hotel room during some of the testing.

Officials got the tabulators back weeks or months later, in one instance at a meeting in a carpool parking lot. DePerno has denied any wrongdoing, as has Leaf, the Barry County sheriff. The DePerno campaign issued a statement calling the petition for a special prosecutor “an incoherent liberal fever dream of lies.”

Once election officials lose control of voting machines, the machines can no longer be used because of the risk of hacking. Moreover, voters can lose faith in the country’s electoral infrastructure when they hear about machines that have not been adequately protected, election experts warn.

Until recently, said Tammy Patrick, who works with election officials around the country as a senior adviser at the nonprofit Democracy Fund, “it seemed far-fetched that election networks could be exposed” in the way they were in Michigan. “Unfortunately, we have a number of instances in the last year or so where this sort of thing has happened around the country,” she said. “It is deeply troubling.”

Michigan Secretary of State Jocelyn Benson said in an interview with The Washington Post that efforts to “twist the arm of election officials to get them to turn over secure information” are illegal. She said it is important for law enforcement to act “not just to hold accountable those who have been trying to interfere with the process, but to look at the connectivity to see if there is a broader connection, not just in our state, but beyond Michigan to Georgia and Ohio and other states where you see this happening.”

Although the exact nature of connections between efforts in different states to breach machines remains unclear, the situation in Michigan is similar to ones elsewhere in which allegedly unofficial and unauthorized investigators sought evidence of fraud by gaining access to voting equipment. Some of those named in the Michigan case have been connected to cases elsewhere.

In Colorado, the Mesa County clerk, Tina Peters, was indicted in March on charges stemming from her effort to allow allegedly unauthorized people to copy the hard drives of voting machines in her county. Peters has denied wrongdoing. In Coffee County, Ga., a cybersecurity executive named in the Michigan case, Benjamin Cotton, said in court filings that he gained access to the county’s voting system information. In Pennsylvania, the secretary of state ordered the decertification of machines in Fulton County after she said they were improperly accessed by individuals seeking to investigate the 2020 election.

Election experts are worried that in some of these intrusions, voting tabulators may have been compromised or the exposure of serial numbers and other details about voting systems could make them more vulnerable to fraud. More broadly, they said, these instances undermine trust in voting.

For months, few knew about the review of voting machines by Leaf, the Barry County sheriff, who belongs to a “constitutional sheriffs” association that contends sheriffs must answer to voters but not state or federal authorities. His team told clerks to keep their visits quiet, according to clerks.

Barry County Clerk Pamela Palmer learned of the investigation in June 2021 and confronted Deputy Sheriff Kevin Erb and investigator Michael Lynch to ask why she had not been told about their work. “They said, ‘Well, we’re kind of doing this under the element of surprise.’ I said, ‘What have you got to hide?’ So that is kind of what started it all,” Palmer said. Reuters and the Detroit News reported earlier on the scope of Leaf’s investigation.

Barry County’s top prosecutor, Julie Nakfoor Pratt, met with Leaf and his attorney, Stefanie Lambert, as well as others last summer to find out what they were doing. Lambert pressed Pratt to issue search warrants and tried to shape how she handled the case, Pratt said. She told Lambert that Leaf had not demonstrated he had probable cause to inspect the voting machines. “I stood my ground and I just told her, you’ve got to go with what you have and if you don’t have it, you don’t have it,” Pratt said.

In a written statement, Lambert said the group’s inquiries into voting machines were appropriate. Her statement echoed ones issued by DePerno and Logan that criticized the attorney general. “Legitimate investigations on behalf of elected constitutional officers in the course of determining whether there was election day fraud is not a crime,” Lambert said in her statement.

Hawthorne, the clerk from Rutland Charter Township, was baffled by the theories presented to her during her meeting with Erb and Lynch about votes being shifted from Trump to Biden in a county that Trump won by a nearly 2-to-1 margin.

“They seem to think there was some kind of microchip in our tabulators that was throwing votes to Biden,” Hawthorne said. “But Trump won Barry County. He won by 65 percent of the vote, so I don’t know where they’re thinking that any kind of chips were in any of our machines or thinking that something had happened to them. The whole thing is nutty. It is nutty, totally nutty.”

The attorney general’s petition for a special prosecutor contends DePerno, Lambert and state Rep. Daire Rendon (R) “orchestrated a coordinated plan to gain access to voting tabulators.” Among others, the petition also mentions Leaf, Cotton and former Cyber Ninjas chief executive Doug Logan. His company was involved with a months-long Republican-driven review of ballots in Arizona that election experts said was sloppily handled.

The clerks willingly gave up their voting equipment to someone described only as Person 1 in a letter from Chief Deputy Attorney General Christina Grossi. After Roscommon County Clerk Michelle Stevenson handed over a tabulator and flash drives, she began to question the authority of the investigation. A state representative, unnamed in Grossi’s letter, told Stevenson she was doing the right thing and assured her that her name would never come up.

Those who obtained the voting machines held on to them for weeks or months, causing the clerks to grow “apprehensive,” Grossi’s letter explains. The machines were returned in meetings at a shopping center and carpool parking lot.

Leaf is continuing his work and in June asked a state court to take the extraordinary step of halting the attorney general’s investigation into his efforts to prove fraud in the 2020 election. Last month at a Las Vegas conference of the Constitutional Sheriffs and Peace Officers Association he lamented that he had not persuaded Pratt, the county prosecutor, to pursue search warrants.

“We’re going to keep moving forward, folks. We’re not done with this,” Leaf said, suggesting he might seek to prosecute alleged election fraud using a common law grand jury, an unofficial body that some claim can issue indictments.

Nessel’s request for a special prosecutor, intended to avoid a conflict of interest because her opponent is among those being probed, may mean any attempt to pursue charges in the voting machine breach investigation could move slowly. The Prosecuting Attorneys Coordinating Council in Michigan, which assigns special prosecutors in cases of conflict of interest, can take up to 90 days to arrange for a prosecutor to step in, said Cheri Bruinsma, the group’s executive director.

On Friday, the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law sent a memo to organizations representing thousands of local election officials nationwide advising them of the growing problem of machine breaches and how to respond to it. “Public confidence in future elections can be severely damaged by plausible allegations that unauthorized or biased actors have been given physical access to voting equipment,” the memo says.

The memo urges officials to have a plan in place to quickly investigate possible breaches of voting machines and to replace or decommission election equipment if needed. The memo recommends practices to prevent such tampering, including closely restricting access to election systems, instituting background checks on those who have access and installing surveillance cameras.

“It is super important for election officials to know these breaches of election security are occurring and that there have been swift and strong reactions to it,” said Lawrence Norden, director of elections and government for the Brennan Center. “We want to be sure local election officials know they have an obligation to detect and quickly take remedial action if a breach occurs.”

Hawthorne, the clerk in Rutland Charter Township, said she and other clerks in Michigan are trained never to give up their voting machines. She said was shocked to hear some had handed them over and stunned that Leaf, the sheriff in her county, was spending so much time on what she considers a misguided investigation.

“He thinks that there is some kind of massive thing going on in Barry County, which I don’t understand,” Hawthorne said. “We’re just a tiny little county in Michigan. We can’t really affect the voting results in any way, shape or form.”

After the Taliban seized power in Afghanistan, women and girls have had their lives disrupted and plans upended after losing the ability to attend school or work. (photo: CBC)

After the Taliban seized power in Afghanistan, women and girls have had their lives disrupted and plans upended after losing the ability to attend school or work. (photo: CBC)

We were at the Rwanda campus of the School of Leadership, Afghanistan — the boarding school for Afghan girls I founded — this Afghan girl and I, not long ago. She and her classmates were taking swimming lessons in our pool. She was in the deep end. I was standing at poolside. And she’d just let go of the wall.

“I can,” I said. I watched her legs kicking as she treaded water. “You’re staying up. You’re doing great.”

“Today’s the first day I can do this,” she said, the droplets flying, and her smile was so beautiful. “My goal was to stay above water, and you’re seeing me meet my goal.”

For nearly a year, The Post has granted me the extraordinary privilege of sharing stories of Afghan women: stories of our lives, stories of what it means to be brave in moments large and small.

I’ve shared these stories not to romanticize reality or indulge in easy metaphor. I share them because you need to know that Afghan women will not give up. Ever. Not on themselves and not on each other and not on their nation. I share them because the international community needs to know that engaging with the bravery of Afghan women offers the best chance of lifting my homeland out of the downward spiral the Taliban has set us on.

On Aug. 15, 2021, I locked the gate at our campus in Kabul and walked into the streets as that spiral lurched back into motion. Its momentum has grown merciless. My beautiful country is in economic free fall. Families are starving. Girls like my students are barred from school. Women like me are forbidden from working.

In my very first column, I asked you not to look away from Afghanistan. I wrote: “Educated girls grow to become educated women, and educated women will not allow their children to become terrorists. The secret to a peaceful and prosperous Afghanistan is no secret at all: It is educated girls.”

And so today, one year down the spiral, as the world follows news of the death of al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri at his hideaway in Kabul, girls walk into secret schools on the outskirts of our city. They learn English, and they learn art. In living rooms, women gather in secret to strategize ways to fight for the human rights they’ve been denied. As it was in my childhood, so it is again.

Far away from her family in Afghanistan, a girl treaded water in a pool. There were only women at swimming practice that day, as always. Our students were clad in burkinis, as always. Yet there are those in Afghanistan who would still see such healthy recreation as questionable, and I asked this girl: “Do you tell your family about days like this? Do you share these moments with them?”

She used a respectful term of address in responding, but there was no mistaking the incredulity in her voice. “Shabana Jan,” she said, “I share everything with them. They’re so happy that I’m happy and that I’m learning.”

She is studying in Rwanda, but so many girls like her are in refugee camps and back in Afghanistan. I am working in Rwanda, but so many women like me are in refugee camps and back home. In our worldwide exile and in our brutalized homeland, we are one year down the spiral with so much lost. So much taken. And yet there is so much within us that will not, cannot be extinguished.

At the pool that day, girls were splashing, laughing, bobbing below the surface and coming back up, their faces wet and smiling.

“Can you see me?” an Afghan girl asked.

Can you?

NEON workers sample fish in 2019 at Lower Hop Brook in Massachusetts, one of the streams being monitored as part of this long-term ecological study. (photo: NEON)

NEON workers sample fish in 2019 at Lower Hop Brook in Massachusetts, one of the streams being monitored as part of this long-term ecological study. (photo: NEON)

The gas, sulfur hexafluoride, is "the most potent greenhouse gas known to date," according to the Environmental Protection Agency. It's 22,800 times more effective at trapping heat than carbon dioxide, and lasts in the atmosphere for thousands of years.

So far, this ecology study has released around 108 pounds of the gas, which has about the same impact as burning more than a million pounds of coal.

That may not seem like a big deal in the grand scheme of global emissions, but government scientists working at federal parks and forests have objected to using this gas on public lands — especially since this major study is designed to go on for 30 years and alternative gasses are available.

This kerfuffle has so far played out quietly within government agencies. But it comes at a time when all kinds of researchers are thinking about the climate effects of past practices, with some saying that scientists who understand the urgency of the climate crisis have a special obligation to set an example to the public by reducing the greenhouse gas emissions of their own work.

The National Science Foundation (NSF), which funds this large ecology study, told NPR that it supports an evaluation that's now underway to see whether phasing out the use of this gas would affect the quality of the information that's being gathered.

That's not good enough for one watchdog group, which is calling for an immediate halt to the release of this gas on public lands.

"We're using just a tiny amount"

For decades, ecologists have sometimes burbled small amounts of sulfur hexafluoride into streams and rivers, in order to study how quickly gasses can move from the water into the air. One reason that's of interest is that, although inland waterways cover up only a small fraction of the Earth's surface, researchers believe these running waters could be an important source of greenhouse gasses, as rainfall can carry carbon from the ground into turbulent streams that later release it into the atmosphere.

Ecologists have always known that sulfur hexafluoride was itself a potent greenhouse gas, "but we always said, 'Well, we're using just a tiny amount of it," says Bob Hall, a professor of stream ecology at the University of Montana.

"The beauty of sulfur hexafluoride is we only have to add very tiny quantities, and it's really, really easy to measure and it's perfectly unreactive. We're not doing anything to the ecosystem by adding it, it's not reacting with anything, it's not poisoning anything," says Hall, who once calculated that the amount he used in one of his experiments had about the same climate impact as burning 35 gallons of gasoline.

Given the usefulness of this gas in stream studies, it's not surprising that tests involving sulfur hexafluoride were built into the standardized protocols of the National Ecological Observatory Network, or NEON, which is an ambitious government-funded effort to track ecological changes. Its mission is to use consistent methods to collect all kinds of data on 81 different locations across the nation--and to do this regularly for three decades.

"The idea is to understand the effects of things like climate change, land use change, and invasive species on these ecosystems," says Kaelin Cawley, who works at Battelle, the nonprofit applied science and technology organization that operates NEON for the NSF.

The planning for this half-billion-dollar ecological project, and the construction of its monitoring instruments, took around twenty years. It began operating at full tilt in 2019.

That's the same year when a scientist at Yellowstone National Park started to question why NEON was releasing sulfur hexafluoride at Blacktail Deer Creek, according to documents obtained through a public records request by Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility, a group that supports workers within the government who are concerned about activities that can harm the environment.

The environmental consequence

NEON's protocols called for it to annually release around 3.3 pounds of sulfur hexafluoride, or SF6, in Yellowstone National Park, hydrologist Erin White pointed out in a November, 2020 email to another National Park Service official. Over the 30-year lifetime of the project, White calculated, that meant the use of SF6 for research in Yellowstone National Park alone would be equivalent to burning over 1,139,000 pounds of coal.

"In short, the environmental consequence of a small SF6 application in the park is significant," noted White, who recommended that NEON immediately substitute an alternative gas, such as argon, even though NEON staffers thought making this switch would be problematic because of things like lab contracting constraints.

Bobby Hensley, who works on NEON for Battelle, told NPR that the climate impact from the scientific use of this gas has to be kept in perspective.

"I don't want to sort of criticize Yellowstone National Park, but, I mean, there's hundreds of thousands of vehicles driving through that park every single day," says Hensley. "They can't tell people, 'Hey, you can't come visit the park.' But they can say, 'You can't use SF6.'"

Soon, government officials shared the concerns raised at Yellowstone with others who oversaw sites where NEON had been releasing this gas. Emails went out to Great Smoky Mountains National Park, the Bureau of Land Management, and the United States Forest Service. About half of the NEON sites with streams where sulfur hexafluoride was released were on forest service lands, records show.

"SF6 is a potent greenhouse gas and over the 30 year NEON program the release will be equivalent to burning millions of pounds of coal," wrote Bret Schichtel of the National Park Service's Air Resource Division to Linda Geiser, the National Air Program Manager for the Forest Service. "We would like to know if you are aware of this issue and share similar concerns."

In December of 2020, representatives of the park and forest services held a virtual meeting with NEON employees. Emails sent after that meeting make it clear that the public land officials felt a "strong desire" to discontinue the use of this gas.

NEON subsequently convened a group of expert advisers to figure out if they could stop using the gas without disrupting the science.

One of those advisors was Hall, who says that he had already moved away from using SF6 in his own studies of streams, in part because of its extreme potency as a greenhouse gas. "It is somewhat ironic," Hall and a colleague wrote in one paper, "to study carbon cycling using a tracer gas with that much greenhouse forcing."

"This doesn't fit with the mission"

It turns out that the physical features of streams that affect turbulence and gas exchange don't change much over time. So NEON's expert advisers basically felt it would be okay to just make sure this study had some baseline measurements using SF6 for each site and then leave it at that, rather than switching to an alternative gas that would require new instruments and training so that measurements could be taken year after year.

"We have discontinued it recently at several of our sites, but not all of them," says Cawley, who notes that the water level in streams might currently be too low to get the data they want. "Some of the sites, we still need to get certain flow ranges that we haven't covered yet."

The NSF's Program Director for NEON, Charlotte Roehm, told NPR in an emailed statement that Battelle was evaluating the impact of phasing out the use of SF6 and that "the NSF team that manages NEON is supportive of conducting that evaluation."

In 2021, according to one memo sent from NEON to Roehm, NEON used approximately 18 pounds of the gas, which is the equivalent of greenhouse gas emissions from driving an average car over 460,000 miles. That memo stated the new plan was to use the gas to take measurements "up to three times per year at up to 10 sites," likely for one to three more years.

"Eventually we will stop using SF6 when all sites have enough data to draw conclusions about gas exchange rates across a wide range of flows at a site," the memo states.

Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility, however, wants them to stop using SF6 immediately.

"They're doing these experiments on public lands like national parks and national forests," says Chandra Rosenthal, who directs the non-profit's Rocky Mountain office. "This doesn't fit with the mission of these agencies at all."

The government workers who manage those federal lands are unhappy about the use of this gas, she says, "but they haven't really had the authority to do anything about the fact that this stuff is being used."

This week, her group sent a letter to the director of the NSF, asking the agency to stop funding projects that use SF6 on federal lands, and to assess the value of using SF6 and other greenhouse gasses in all the research it funds. A similar letter, sent to U. S. Department of the Interior Secretary Deb Haaland and U. S. Department of Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack, calls on them to stop allowing the use of SF6 on the lands they manage. "It is our understanding," the letter says, "that similar research projects have switched to argon without issue."

One researcher who uses small amounts of SF6 for studies of gas exchange in the ocean, rather than streams, says he thinks NEON's protocols could have been set up differently, to minimize the use of this greenhouse gas.

"If I was to do what they're doing, I would do it differently. I wouldn't be bubbling it in, because that does use a lot," says David Ho, an oceanographer with the University of Hawaii, who explains that he might infuse a small amount of the gas into a bag of water and then release that into the stream. "They haven't thought this through, in terms of the best way to do it."

And even if the amount that's been released by NEON and other scientific studies is essentially nothing compared to the amount of SF6 released globally from industrial sources, the concerns about it still seem reasonable to streams researcher Walter Dodds of Kansas State University, who served on NEON's technical advisory panel.

"It may be an overreaction of sorts, but it's completely understandable as well. We all are worried about what our own footprints are," says Dodds. "Certainly we should be cognizant of the potential for that harm and at least minimize the amount of times we use it and the amount of gas that we use in each experiment."

Special Coverage: Ukraine, A Historic Resistance

READ MORE

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.