Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

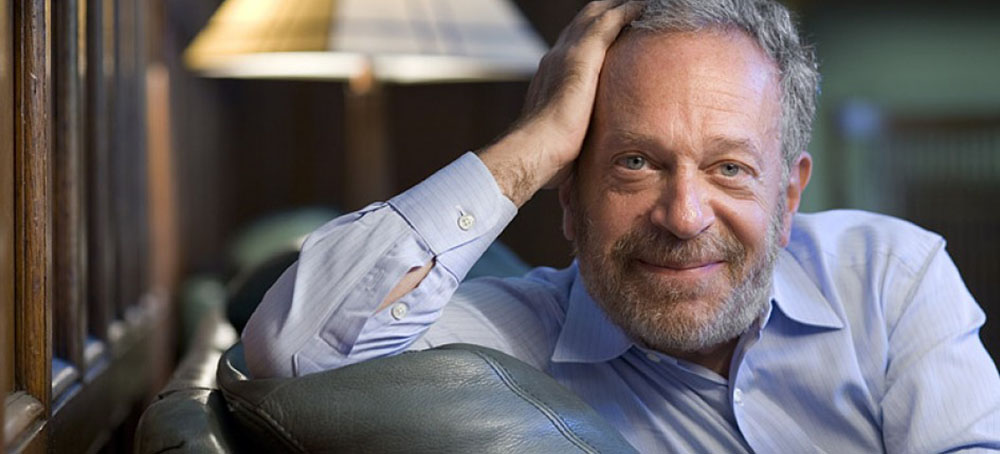

Personal thoughts about whether he should run again

I don’t think this reflects an “ageist” prejudice against those who have reached such withering heights so much as an understanding that people in their late 70s and 80s wither.

I speak with some authority. I’m now a spritely 76 — lightyears younger than our president. I feel fit, I swing dance and salsa, and can do 20 pushups in a row. Yet I confess to a certain loss of, shall we say, fizz.

Joe Biden could easily make it until 86, when he’d conclude his second term. After all, it’s now thought a bit disappointing if a person dies before 85. My mother passed at 86, my father two weeks before his 102nd birthday (so I’m hoping for the best, genetically speaking). Three score and ten is the number of years of life set out in the Bible. Modern technology and Big Pharma should add at least a decade and a half. Beyond this is an extra helping. “After 80, it’s gravy,” my father used to say.

Joe will be on the cusp of the gravy train.

Where will it end? There’s only one possibility, and that reality occurs to me with increasing frequency. I find myself reading the obituary pages with ever greater interest, curious about how long they lasted and what brought them down. I remember a New Yorker cartoon in which an older reader of the obituaries sees headlines that read only “Older Than Me” or “Younger Than Me.”

Yet most of the time I forget my age. The other day, after lunch with some of my graduate students, I caught our reflection in a store window and for an instant wondered about the identity of the short old man in our midst.

It’s not death that’s the worrying thing about a second Biden term. It’s the dwindling capacities that go with aging. "Bodily decrepitude," said Yeats, "is wisdom." I have accumulated somewhat more of the former than the latter, but our president seems fairly spry (why do I feel I have to add “for someone his age?”). I still have my teeth, in contrast to my grandfather whom I vividly recall storing his choppers in a glass next to his bed, and have so far steered clear of heart attack or stroke (I pray I’m not tempting fate by my stating this fact). But I’ve lived through several kidney stones and a few unexplained fits of epilepsy in my late thirties. I’ve had both hips replaced. And my hearing is crap. Even with hearing aids, I have a hard time understanding someone talking to me in a noisy restaurant. You’d think that the sheer market power of 60 million boomers losing their hearing would be enough to generate at least one chain of quiet restaurants.

When I get together with old friends, our first ritual is an “organ recital” — how’s your back? knee? heart? hip? shoulder? eyesight? hearing? prostate? hemorrhoids? digestion? The recital can run (and ruin) an entire lunch.

The question my friends and I jokingly (and brutishly) asked one other in college—"getting much?"—now refers not to sex but to sleep. I don’t know anyone over 75 who sleeps through the night. When he was president, Bill Clinton prided himself on getting only about four hours. But he was in his forties then. (I also recall cabinet meetings where he dozed off.) How does Biden manage?

My memory for names is horrible. (I once asked Ted Kennedy how he recalled names and he advised that if a man is over 50, just ask “how’s the back?” and he'll think you know him.) I often can’t remember where I put my wallet and keys or why I’ve entered a room. And certain proper nouns have disappeared altogether. Even when rediscovered, they have a diabolical way of disappearing again. Biden’s secret service detail can worry about his wallet and he’s got a teleprompter for wayward nouns, but I’m sure he’s experiencing some diminution in the memory department.

I have lost much of my enthusiasm for travel and feel, as did Philip Larkin, that I would like to visit China, but only on the condition that I could return home that night. Air Force One makes this possible under most circumstances. If not, it has a first-class bedroom and personal bathroom, so I don’t expect Biden’s trips are overly taxing.

I’m told that after the age of 60, one loses half an inch of height every five years. This doesn’t appear to be a problem for Biden but it presents a challenge for me, considering that at my zenith I didn’t quite make it to five feet. If I live as long as my father did, I may vanish.

Another diminution I’ve noticed is tact. A few days ago, I gave the finger to a driver who passed me recklessly. These days, giving the finger to a stranger is itself a reckless act. I’m also noticing I have less patience, perhaps because of an unconscious “use by” timer that’s now clicking away. Increasingly I wonder why I’m wasting time with this or that buffoon. I’m less tolerant of long waiting lines, automated phone menus, and Republicans. Cicero claimed "older people who are reasonable, good-tempered, and gracious bear aging well. Those who are mean-spirited and irritable will be unhappy at every stage of their lives." Easy for Cicero to say. He was forced into exile and murdered at the age of 63, his decapitated head and right hand hung up in the Forum by order of the notoriously mean-spirited and irritable Marcus Antonius.

How the hell does Biden maintain tact or patience when he has to deal with Mitch McConnell? Or Joe Manchin, for crying out loud?

The style sections of the papers tell us that the 70s are the new 50s. Septuagenarians are supposed to be fit and alert, exercise like mad, have rip-roaring sex, and party until dawn. Rubbish. Inevitably, things begin falling apart. My aunt, who lived far into her nineties, told me “getting old isn’t for sissies.” Toward the end she repeated that phrase every two to three minutes.

Philosopher George Santayana claimed to prefer old age to all others. "Old age is, or may be as in my case, far happier than youth," he wrote. "I was never more entertained or less troubled than I am now." True for me too, in a way. Despite Trump, notwithstanding the seditiousness of the Republican Party, the ravages of climate change, near record inequality, a potential nuclear war, and a stubborn pandemic, I remain upbeat -- largely because I still spend most days with people in their twenties, whose fizz buoys my spirits. Maybe Biden does, too.

But I’m feeling more and more out of it. I’m doing videos on TikTok and Snapchat, but when my students talk about Ariana Grande or Selena Gomez or Jared Leto, I don’t have clue who they’re talking about (and frankly don’t care). And I find myself using words –- “hence,” “utmost,” “therefore,” “tony,” “brilliant” — that my younger colleagues find charmingly old-fashioned. If I refer to “Rose Marie Woods” or “Jackie Robinson” or “Ed Sullivan” or “Mary Jo Kopechne,” they’re bewildered. The culture has flipped in so many ways. When I was seventeen, I could go into a drugstore and confidently ask for a package of Luckies and nervously whisper a request for condoms. Now it’s precisely the reverse. (I stopped smoking long ago.)

Santayana said the reason that old people have nothing but foreboding about the future is that they cannot imagine a world that’s good without themselves in it. I don’t share that view. To the contrary, I think my generation — including Bill and Hillary, George W., Trump, Newt Gingrich, Clarence Thomas, Nancy Pelosi, Chuck Schumer, and Biden – have fucked it up royally. The world will probably be better without us.

Joe, please don’t run.

That timeframe is an informal commitment to pass a package along the lines of what Sen. Joe Manchin (D-W.Va.) has pushed for. (photo: Tom Williams/AP)

That timeframe is an informal commitment to pass a package along the lines of what Sen. Joe Manchin (D-W.Va.) has pushed for. (photo: Tom Williams/AP)

The president called for the quicker passage of a smaller reconciliation bill that would address prescription drugs and health care subsidies and leave climate till later.

In a statement issued by the White House, Biden pledged to tackle climate change and clean energy through executive action, should Congress not act legislatively. But he also asked Senate leadership to pass a narrow bill that would “give Medicare the power to negotiate lower drug prices and to prevent an increase in health insurance premiums for millions of families,” and to do so before the August recess.

That timeframe is an informal commitment to pass a package along the lines of what Manchin has pushed for. The West Virginia Democrat told party leadership this week that he would not support a larger bill that included climate provisions and tax increases. He clarified on Friday that he might be able to support those measures but only after July’s inflation report comes in. That would require Congress to wait until after the August recess with continued uncertainty if Manchin would even support the final measure.

Biden, in his statement, all but told lawmakers not to take such a risk.

“Families all over the nation will sleep easier if Congress takes this action,” he said. “The Senate should move forward, pass it before the August recess, and get it to my desk so I can sign it.”

Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer and Senate Democrats are planning to move forward next week on the prescription drug price deal, a Senate Democratic aide said Friday afternoon. But they need to make sure it will pass muster with the Senate parliamentarian to conform to the strict budget rules governing the so-called “reconciliation” process, which allows legislation to pass with a simple majority.

Biden’s statement comes after the White House for months largely left negotiations with Manchin up to Schumer. But after Manchin issued his latest ultimatum, Biden wasted little time wading in to head off an intra-party feud.

“Democrats have come together, beaten back the pharmaceutical industry and are prepared to give Medicare the power to negotiate lower drug prices and to prevent an increase in health insurance premiums for millions of families,” Biden said in his statement.

The conciliatory tone stood in contrast to the deep disappointment rippling through much of the rest of the party. Democrats’ planned climate, tax and prescription drugs bill already represented a far smaller package than the $1.5 trillion plan negotiated last year, before Manchin blew up those talks in December.

Now, after effectively asking Manchin for months to write his preferred legislation, Democrats’ remaining best-case scenario is passing drug price reforms and a temporary extension of enhanced Obamacare subsidies. The subsidy continuation Manchin has requested would force the party to confront the prospect of rising premiums again in two years — just ahead of a presidential election.

Party operatives also worry the slow whittling down of the bill has decimated enthusiasm among the Democratic base, as voters watched popular provisions stripped away one by one. For decades, Democrats sought a major prescription drugs overhaul, said one person close to Democratic leadership. But now, on the verge of making it happen, it feels like a consolation prize.

“The damage caused by this endless waiting game doesn’t get you results,” the person said, “and further increases the grassroots disenchantment and keeps Biden from doing things elsewhere.”

Democratic lawmakers throughout Friday teed off on Manchin over his rejection of a broader reconciliation deal, blasting him as untrustworthy and lamenting the months spent trying to reach an agreement.

“Whenever he sends mixed signals, the signal to me is really clear,” said Rep. Dan Kildee (D-Mich.). “Anything that’s not absolutely yes, today is no when it comes to Joe.”

The White House would eventually arrive at the same conclusion. Officials on Friday morning initially latched onto Manchin’s suggestion on a West Virginia radio show that his position had been misrepresented — hoping there might still be an immediate path toward a deal that included climate and tax provisions.

Democrats, Manchin told radio host Hoppy Kercheval, are trying to “put all this pressure on me. I am where I have been. I would not put my staff through this. I will not put myself through this if I wasn’t sincere about trying to find a pathway forward to do something good for our country.”

But it quickly became clear that would mean waiting until September, raising the risk that Manchin could pull out once again and leave Biden empty-handed just before the midterms. The White House and Democratic leaders had already spent months trying to negotiate a deal that fit Manchin’s specific parameters, only to see him alter his demands in the final stages. There was no guaranteeing it wouldn’t happen yet again.

“We’re all frustrated and infuriated and we still have to do what we can to scrape any small victories out of this divided Senate,” Sen. Ed Markey of Massachusetts said in an interview. “I think President Biden is committed on the climate issue. I think he’s disappointed that this has fallen apart.”

Speaking to reporters from Saudi Arabia Friday afternoon, Biden was asked if he felt Manchin had been an honest broker during the negotiations.

“I didn’t negotiate with Joe Manchin,” he responded. “I have no idea.”

People walk by debris of a destroyed local market after a Russian missile attack in the town of Bakhmut, Donetsk region, Ukraine. (photo: Anatolii Stepanov/AFP)

People walk by debris of a destroyed local market after a Russian missile attack in the town of Bakhmut, Donetsk region, Ukraine. (photo: Anatolii Stepanov/AFP)

Russian forces fire missiles and shells across Ukraine after military announces it is stepping up its onslaught.

Russian Defence Minister Sergei Shoigu gave “instructions to further intensify the actions of units in all operational areas, in order to exclude the possibility of the Kyiv regime launching massive rocket and artillery attacks on civilian infrastructure and residents of settlements in the Donbas and other regions,” his ministry said on Saturday.

Russia’s military campaign has been focusing on the eastern Donbas region, but the new attacks hit areas in the north and south as well. Kharkiv, Ukraine’s second-largest city, has seen especially severe bombardments in recent days, with Ukrainian officials and local commanders voicing fears that a second full-scale Russian assault on the northern city may be looming.

At least three civilians were killed and three more were injured on Saturday in a pre-dawn Russian rocket attack on the northern Ukrainian city of Chuhuiv, which is close to Kharkiv and only 120km (75 miles) from the Russian border, a regional police chief said.

Serhiy Bolvinov, the deputy head of Kharkiv’s regional police force, said the rockets partly destroyed a two-storey apartment building.

“Four Russian rockets, presumably fired from around (the Russian city of) Belgorod at night, at about 3:30am, hit a residential building, a school and administrative buildings,” Bolvinov wrote on Facebook. He said the bodies of the three dead civilians were found under the rubble.

In the neighbouring Sumy region, one civilian was killed and at least seven more were injured after Russians opened mortar and artillery fire on three towns and villages not far from the Russian border, regional governor Dmytro Zhyvytsky said Saturday on Telegram.

In the embattled eastern Donetsk region, seven civilians were killed and 14 wounded in the last 24 hours in attacks on cities, its governor said Saturday.

Later in the day, on the outskirts of Pokrovsk, a city in the Donetsk region, a woman said a neighbour was killed by a rocket attack Saturday afternoon. Tetiana Pashko told The Associated Press she herself suffered a cut on her leg, and one of her family’s dogs was killed.

She said her 35-year-old neighbour, killed while in her front yard, had evacuated earlier this year as authorities had requested but had returned home after being unable to support herself. Several homes on a quiet residential street were damaged, with doors and roofs torn up or ripped away.

In the neighbouring Luhansk region, Ukrainian troops repelled a Russian overnight assault on a strategic eastern highway, regional governor Serhiy Haidai said, adding that Russia had been attempting to capture the main road between the cities of Lysychansk and Bakhmut for more than two months.

“They still cannot control several kilometres of this road,” Haidai wrote in a Telegram post.

The Luhansk and Donetsk regions make up the Donbas, an eastern industrial region that used to power Ukraine’s economy and has mostly been taken over by Russian and separatist forces.

In Ukraine’s south, two people were wounded by Russian shelling in the town of Bashtanka, northeast of the Black Sea city of Mykolaiv, according the regional governor, Vitaliy Kim. He said Mykolaiv itself came under renewed Russian fire before dawn Saturday. On Friday, he posted videos of what he said was a Russian missile attack on the city’s two largest universities and denounced Russia as “a terrorist state”.

In Odesa, a port city on the Black Sea, a Russian missile hit a warehouse, engulfing it in flames and sending up a plume of black smoke, but no injuries were reported, local officials said.

Russia accused of shelling from captured nuclear plant

Two people were killed and a woman was hospitalised after a Russian rocket hit the eastern riverside city of Nikopol, emergency services said. Dnipro regional governor Valentyn Reznichenko said a five-storey apartment block, a school and a vocational school building were damaged.

Ukraine’s atomic energy agency accused Russia of using Europe’s largest nuclear power plant to store weapons and shell the surrounding regions of Nikopol and Dnipro that were hit Saturday.

Petro Kotin, president of Ukrainian nuclear agency Energoatom, called the situation at the Zaporizhzhia nuclear plant “extremely tense” with up to 500 Russian soldiers controlling the plant.

The plant in southeast Ukraine has been under Russian control since the early weeks of Moscow’s invasion, though it is still operated by Ukrainian staff.

“The occupiers bring their machinery there, including missile systems, from which they already shell the other side of the river Dnieper and the territory of Nikopol,” he said in a Ukrainian television interview broadcast Friday.

The Ukrainian air force said Russian forces fired six more cruise missiles on Saturday from strategic bombers in the Caspian Sea, and two hit a farm in the Cherkasy region along the Dnieper River. No one was hurt, but agricultural equipment was destroyed and some cattle were killed, regional governor Ihor Taburets said.

The Ukrainian air force said the other four missiles were intercepted.

On Friday, cruise missiles fired by Russian bombers struck Dnipro, a major city in southeastern Ukraine on the Dnieper River, killing at least three people and wounding 16, Ukrainian officials said. In a news briefing Saturday, Russian defence officials claimed that the attack had destroyed “workshops producing components for, and repairing, Tochka-U ballistic missiles, as well as multiple rocket launchers”.

Ukraine’s Interior Ministry said Friday that Russian forces have conducted more than 17,000 attacks on civilian targets during the war, killing thousands of fighters and civilians and driving millions from their homes.

(photo: Katie Martin/The Atlantic/Getty Images)

(photo: Katie Martin/The Atlantic/Getty Images)

The acclaimed poet Gulnisa Imin is serving a 17-year sentence because her work supposedly promotes “separatism.” She’s still writing.

One of those imprisoned is Gulnisa Imin, a Uyghur-literature teacher and an acclaimed poet who was among the roughly 1 million Uyghurs sent to China’s sprawling network of so-called reeducation camps in 2018. A year later, she was sentenced to more than 17 years in prison, reportedly on the grounds that her poetry promoted “separatism.” Imin’s work is not overtly political, in fact, but her poems bear their own kind of witness to the Uyghur experience since China’s mass-internment program began:

Where the words are banned to be said

The flowers are not allowed to blossom

And the birds cannot sing freely

Abduweli Ayup, a Uyghur linguist based in Norway and a friend of Imin’s, told me that prior to her detention, she had self-published a series of poems inspired by One Thousand and One Nights online. Like the character Scheherazade, who tells a story each night to forestall her execution, Ayup said, Imin believed that “her poetry would save her” somehow from erasure. Before her arrest, she had published nearly 350 poems.

But it appears that, even deprived of her liberty, Imin did not stop composing poems. On April 18, 2020, Ayup received a series of messages over the Chinese social-networking app WeChat from someone close to Imin (whom, for their protection, Ayup declined to name). The messages contained photos of several poems scrawled in a notebook dating to the previous month, which Ayup recognized by the handwriting and style as the work of Imin.

When I asked him how her poems could have reached the sender who’d passed them to him, he told me that he had no sure way of knowing. The WeChat account used to transmit the poems was deactivated soon after—a measure he attributed to the sender’s need to reduce their risk of exposure. “People use that technique when they send something outside” China, Ayup said. “And you cannot contact [them] again.” Many Uyghurs living abroad have told me that they no longer keep in touch with loved ones in Xinjiang for fear of endangering them.

In the course of trying to authenticate the poems, I spoke with Joshua L. Freeman, a historian of modern China at Taiwan’s Academia Sinica research institute and a leading translator of Uyghur poetry into English. He provided The Atlantic with translations of two of the poems and agreed with Ayup’s assessment of their provenance. Although he allowed that they could not prove the poems were Imin’s, he was familiar with the scenario. Freeman had spent several years living in the Uyghur capital of Ürümqi, and in 2020 he received a poem from a former professor of his, Abduqadir Jalalidin. Jalalidin was, like Imin, in detention; in his case, the poem had been smuggled out by inmates who, before being released from the camp, had committed Jalalidin’s verses to memory.

For Imin and Jalalidin to choose poetry as their way of communicating with the outside world came as no surprise to Freeman, who told me that Uyghurs have long relied on poetry as a source of solidarity and strength in hard times. Poems—which can be composed, recited, and memorized even without pen or paper—have become a favored literary form during this historic ordeal for the Uyghur people.

“Poetry for many Uyghurs is not just a form of resistance; it’s a form of self-expression in an environment where self-expression is nearly impossible in many contexts,” he said. “Poets in Uyghur society are, to a very significant extent, the voices of their people.”

“Aybéke”

If you don’t hear my familiar voice

In the moonless nights of your sky

Where were you searching for my star

Amidst days that looked sadly to youFor you I would give everything

Leave my body in the distant wilderness

Hope has frosted over, yet you remain

A drop of dew on wilted flowersWho strokes your head while I am gone

My companions now are worry and regret

Each day without you is fire in my throat

No choices left, I’m nothing but wounds— March 27, 2020

“Untitled”

When you think of me, shed no tears of grief

You must not fade away for those who’ve gone

If now and then you find me in your dreams

You must not look with longing down the roadSome things in life remain beyond our reach

Hold no anger in your heart on my account

Ask no news of me from people that you meet

Your thoughts of me must not weigh on your soulJust think of me as someone on a journey

If I’m alive, one day I shall return

I won’t give up on happiness so easily

There is much more that I still ask of lifeBoth of my stars have now been left among you

Please cherish them for me while I am gone

With the kindness that raised me up from childhood

Let them live within your sheltering embrace— March 29, 2020

We shouldn't conflate the right to housing with the right to ownership, which would make affordability a permanent issue. (photo: Jordan Vonderhaar/Bloomberg/Getty Images)

We shouldn't conflate the right to housing with the right to ownership, which would make affordability a permanent issue. (photo: Jordan Vonderhaar/Bloomberg/Getty Images)

Free-market champions conflate homeownership and the human right to adequate shelter. To actually solve the housing crisis, we must challenge this mistaken idea.

Channeling anger at the market’s obscenities, Poilievre blames the Bank of Canada for inflating asset values and “big city gatekeepers” for blocking the building of new housing. Homeownership, he rails in a recent campaign video, “used to be a right. And it should be again.”

Poilievre may not have any serious policy proposals for actually fixing the crisis, but his jeremiads represent an important example of how housing is often discussed. Of all Poilievre’s messaging, the idea that homeownership should be a right — an inalienable entitlement extended to everyone, at least theoretically — resonates deeply with voters. After all, over the course of the twentieth century, homeownership has become central to the North American ideal of a decent, middle-class living.

In fact, the contemporary crisis is often understood, in news media and beyond, primarily as a crisis of ownership. The line of thinking goes like this: huge swaths of the middle class — those would-be homeowners in another, fairer generation — can’t reach the rungs on the property ladder because of NIMBYs and foreign investors. Poilievre simply personifies a broad frustration that spans the spectrum of political thought.

Deploying the language of rights therefore seems to be an appropriate response to these housing-market failures. It sounds good. It sounds fair. It harkens back to the left-wing idea that housing is a human right — an intoxicatingly attractive idea gathering momentum across the world.

But we shouldn’t conflate the right to housing with the right to ownership. While the former could serve as a basis for helping Canada escape its housing woes and secure an affordable life for everyone, the latter won’t. On the contrary, thinking of housing primarily in terms of ownership makes the crisis only more impossible to solve.

We need to think outside the market — not expand it.

The Ownership Trap

Homeownership has long been a much-vaunted ideal in both Canada and the United States, particularly since its rapid postwar expansion. While renting has historically been more prominent in Canada — owing in part to better social welfare and fewer economic inducements for ownership — both countries, especially in the last thirty years, have demonstrated a broad-based bias toward owning.

For the average Canadian or American, home ownership is a sensible and obvious move — not solely in an aesthetic or philosophical sense but an economic one. Sure, owning a house brings with it a sense of autonomy and pride. But its most valuable aspect is that it is an asset. When people buy houses, they are buying equity.

Few investments for working people are, or could be, as practical as the home: rising property values help fund a whole suite for goods, like retirement, postsecondary education for kids, renovations, and consumer spending. As collateral via debt, or through its outright sale, the home can generate a windfall of wealth to fund the components of a decent life. And in retirement, owning one’s home helps people hang on to more of their wealth — instead of it going to landlords or banks. And crucially, it’s possible to turn what would be rent payments into mortgage payments, thereby enabling investment for working people who otherwise would be unable to make monthly investment contributions.

For much of the twentieth century — and even up until the 2008 financial crisis — a large mass of Canadians and Americans could benefit from the housing market’s continual expansion. Of course, there were occasional setbacks and crashes. And the benefits were not a universal phenomenon: much of the working poor, especially those reliant on income supports, were left out and relegated to often underfunded public housing projects or slumlord-provided rental living. The growth of a decent public housing alternative was hobbled by the real estate lobby, austerity-inclined politicians, and property value–obsessed homeowners themselves.

Even so, from after World War II until the crash, a large proportion of the population ascended into the ownership class. High wages and decent jobs throughout capitalism’s postwar “golden age” helped facilitate the trend, while cultural biases toward ownership — a kind of “middle-class birthright,” as Rick Perlstein once noted — emboldened it.

And while these biases might persist, the context has shifted. Since the 1990s, housing has become much more of an investment commodity, a sector which generates billions of dollars in profit for real estate investment trusts (REITs), corporate landlords, small-scale real estate investors, and massive investment-fund portfolios. It’s become a tradable good, bought and sold globally and gambled on in financial markets.

With lax regulations, low interest rates, and meager public housing, the real estate sector has ballooned in size for two decades. House prices have soared, and rents along with them. One perverse outcome is that, because of our weak social safety nets in Canada and the United States, homeowners find themselves allied with the investors inflating the sector, hoping home values steadily grow in order to secure retirement or fund postsecondary education for their children. For many, it creates a stunning but little-discussed contradiction: they want housing to be affordable for their neighbors, but they want housing values to increase, too.

Due to state retrenchment, we ask housing to do a lot for us — far beyond the primary goal of housing people. A popular response to the problems caused by the housing market is the notion that investors can simply be kicked out of the market in order to make housing more affordable, thereby extending ownership to more people. This idea seems very attractive, even intuitive. It is the reason why calls for taxes on the foreign investor bogeyman are so common. But even at its most inclusive, a country’s housing market confers its ersatz social safety net only on parts of the population. And unlike universal benefits that would be of advantage to everyone, that social safety net could also easily disappear in a market crash — a likely eventuality after decades of investors treating housing like a casino.

Fixing the Crisis

A real exit from the housing crisis — one that would enable the construction of a fairer and more prosperous world for everyone — requires disentangling housing from these other concerns and returning it to its original function: to house people. But doubling down on ownership won’t serve that goal. Policies that aim to induce more ownership in Canada — a country where two-thirds of the population already own homes — will only inflate the market further, creating more dependency on its continued growth.

Investors, too, will continue taking advantage of the seemingly never-ending demand for homes. Higher interest rates, better regulation, and an increase in housing stock supply will not stop housing-market investment and speculation. The fight to bring down housing costs requires much more aggressive and interventionist measures than economic inducements for workers or simply building more homes.

Throwing cold water on the idea of mass ownership might sound tantamount to recommending that workers should have lower expectations. But it is only through breaking out of the ownership straitjacket that a fairer, more affordable world might be secured.

Fixing the housing crisis requires working outside the market. A wholesale overhaul of our social safety net would be a great start: a massive expansion of public retirement benefits, free postsecondary education, and beautiful, far-under-market public housing projects. Look no further than some Scandinavian countries where long-term renting — especially in high-quality public housing — is a viable and decent option for families, especially those for whom buying might never be an option.

Well-funded nonmarket housing in particular can be an effective escape valve from the two choices that face most people: buying in a red-hot market — something that is impossible for many workers — or renting from unscrupulous and greedy landlords. Solid public housing paired with generous universal benefits would much more effectively deliver affordability to the working class, as well as peace of mind in retirement. For half a century, ownership has been a key ticket to prosperity — a scenario that’s created a slew of new problems.

A significant shift in the balance of power is necessary for these suggestions to be realized. It requires a total break from the logic of neoliberalism that has shaped housing policies in Canada and the United States for a century. But organized socialists, tenants, and activists can push that project forward.

Housing as a Human Right

Making the claim that housing is a human right — housing that is high-quality, secure, affordable, and safe — can help build support for a significant build-out of public housing. But when discussing housing as a right, we have to be specific: housing, not ownership.

For socialists, a central task in the fight to solve the housing crisis will be rejecting the idea that broad-based home ownership is a form of housing justice. We must broadcast the failure of imagination in play when housing rights and mass-market ownership are conflated as the same desirable thing.

Obscuring the difference between housing provision (as a social good) and ownership (as part of a zero-sum game) allows right-wing politicians like Poilievre — a landlord himself, who no doubt wants to see home values increase ever upward — to deploy the language of housing rights. Most nefariously, treating rights and ownership as the same thing ensures that the housing crisis will be an interminable problem, thereby preventing us from directing our energies into effective and real solutions.

Freshly cut eucalyptus awaits transportation in the Comexatibá Indigenous Territory in Bahia state, Brazil. (photo: Sarah Sax/Mongabay)

Freshly cut eucalyptus awaits transportation in the Comexatibá Indigenous Territory in Bahia state, Brazil. (photo: Sarah Sax/Mongabay)

In a video manifesto released on June 26, a Pataxó leader stands flanked by two other men in front of a mass of burning eucalyptus trees. “We are expelling the multinationals, the millionaires and billionaires from here,” he says to the camera. “There won’t be a single eucalyptus tree left on our sacred land, because that’s bad. We want our water, quality land, and our biome recovered. We do not accept this shameful destruction.”

On June 22, 180 Indigenous people took over Fazenda Santa Bárbara, a plantation that was used for cattle raising and also growing eucalyptus trees for multinational pulp production company Suzano. According to Indigenous leaders, the area occupied by the farm falls entirely within the perimeter of the Comexatibá (Cahy-Pequi) Indigenous Territory, which spans 28,000 hectares (69,000 acres) north of the city of Prado, one of the first places of Portuguese colonizers’ contact with South America’s native peoples in the 1500s.

On June 25, another group of around 100 Pataxó took over a different farm, largely abandoned pasture, in the Barra Velha do Monte Pascoal Indigenous Territory. The following day, the landowners and their supporters allegedly expelled the Indigenous people from the area at gunpoint, according to a report by the Indigenist Missionary Council (CIMI), an Indigenous rights advocacy group that’s affiliated with the Catholic Church.

Both cases hang in bureaucratic limbo, like many other land rights issues centered on Indigenous territories in Brazil. In 2019 the Superior Court of Justice recognized the legitimacy of the demarcation of the Barra Velha do Monte Pascoal Indigenous Territory. But its final demarcation was blocked by the justice minister, citing an opinion from a former president, Michael Temer. The Comexitibá Indigenous Territory started the process of demarcation in 2005 and was demarcated and approved seven years ago by Funai, the federal agency for Indigenous affairs, but it’s still awaiting presidential approval. Since Jair Bolsonaro took office as president in January 2019, he has not approved any Indigenous territories — in keeping with his campaign promise to demarcate “not another centimeter” of Indigenous lands.

The Comexatibá Indigenous Territory is the site of more land disputes than any other Indigenous territory in Brazil, according to Lethicia Reis, a lawyer at CIMI. The Pataxó not only face pulp production companies, but also expanding tourism and agribusiness sectors, she added in a news release from CIMI.

Eucalyptus is a key economic sector in Brazil, with much of it is grown in the region comprising southeastern Bahia and the neighboring state of Espírito Santo. The region has a long history of conflict involving eucalyptus plantations; activists have been reportedly been killed in land grabs associated with the expansion of eucalyptus. The Landless Workers Movement has occupied plantations, and Afro-Brazilian quilombo communities are increasingly resisting the negative environmental and social impacts of eucalyptus on their traditional lands, activists say.

Suzano, the world’s largest producer of cellulose, has increasingly bought up or merged with smaller pulp and paper companies, according to a U.N. report, and now grow eucalyptus on more than 1 million hectares (2.5 million acres) of land, much of it along Brazil’s Atlantic coast. The company has long touted its green practices, but environmentalists disagree as to how sustainable they really are in practice, Mongabay previously reported. But the position of the Pataxó people is clear: in their manifesto, they called out the multinational company as being partially responsible for the ongoing destruction of their territory.

The eucalyptus species that the company grows are especially damaging to the environment and communities that live around the plantations, environmentalists say. They require large amounts of pesticides that affect water quality, and suck up large amounts of water. “Currently, pulp companies exploit the area by planting eucalyptus trees and this causes serious environmental damage to the entire region, including deforestation and excessive use of pesticides. These practices have been affecting the water resources that still exist in the region,” the Pataxó said in a statement.

In an emailed response to Mongabay, Suzano said it was aware of and monitoring the situation, but stated that “the area is not a formally recognized indigenous land and underwent a detailed environmental licensing process with all notifications and requirements duly fulfilled.” It also said that it “does not own or operate any areas located in indigenous territory,” and that none of its areas in Brazil are “undergoing land ownership requests or court proceedings.” The company said it “adheres to strict standards and specifications and only acquires wood or operates in areas which meet all prerequisites set forth by law and national and international regulatory bodies. To support this, we have undertaken a meticulous mapping of areas where ownership is held by indigenous people.”

Under the Brazilian Constitution, Indigenous lands are legally classified as territories that are traditionally occupied by Indigenous groups, regardless of whether they have concluded the demarcation process, said Ana Carolina Alfinito, the Brazil legal adviser at Amazon Watch. “The Indigenous right to land exists previous to the conclusion of the demarcation process. So in this case, the economic operations going on within the Pataxó territory are illegal,” she told Mongabay by phone.

Since the occupation of Fazenda Santa Barbara on June 22, the groups that have gathered there have been cut off by farmers from outside supplies, including of food and water, and have also been threatened, although there has been no violence, Indigenous leaders said. On July 7, the government of Bahia sent an urgent request for more federal police in the area. The request has so far has gone unanswered, Mãdy Pataxó, an indigenous chief told Mongabay over the phone.

In place of the eucalyptus, the Pataxó have started planting native fruit trees like amesca, imabaúba and sapucaí.

“The Pataxó families need the land for their survival, and to promote Indigenous agriculture, religious practices and protection of existing natural resources,” an Indigenous chief says in a video. “We ask for help from the Brazilian and international authorities and society. Support the Indigenous cause, which is true and legitimate. We can’t take it anymore, this land is our flesh, the water is our blood and the forest is our spirit.

“Pulp, monoculture and extensive farming are destroying everything”, he adds.

Baltimore has been converting its streetlights to LED to save money on energy. LEDs also have less of an impact on plants. (photo: Cyndi Monaghan/Getty Images)

Baltimore has been converting its streetlights to LED to save money on energy. LEDs also have less of an impact on plants. (photo: Cyndi Monaghan/Getty Images)

The big idea

In our study, my colleagues and I analyzed trees and shrubs at about 3,000 sites in U.S. cities to see how they responded under different lighting conditions over a five-year period. Plants use the natural day-night cycle as a signal of seasonal change along with temperature.

We found that artificial light alone advanced the date that leaf buds broke in the spring by an average of about nine days compared to sites without nighttime lights. The timing of the fall color change in leaves was more complex, but the leaf change was still delayed on average by nearly six days across the lower 48 states. In general, we found that the more intense the light was, the greater the difference.

We also projected the future influence of nighttime lights for five U.S. cities – Minneapolis, Chicago, Washington, Atlanta and Houston – based on different scenarios for future global warming and up to a 1% annual increase in nighttime light intensity. We found that increasing nighttime light would likely continue to shift the start of the season earlier, though its influence on the fall color change timing was more complex.

Why it matters

This kind of shift in plants’ biological clocks has important implications for the economic, climate, health and ecological services that urban plants provide.

On the positive side, longer growing seasons could allow urban farms to be active over longer periods of time. Plants could also provide shade to cool neighborhoods earlier in spring and later in fall as global temperatures rise.

But changes to the growing season could also increase plants’ vulnerability to spring frost damage. And it can create a mismatch with the timing of other organisms, such as pollinators, that some urban plants rely on.

A longer active season for urban plants also suggests an earlier and longer pollen season, which can exacerbate asthma and other breathing problems. A study in Maryland found a 17% increase in hospitalizations for asthma in years when plants bloomed very early.

What still isn’t known

How the fall color timing will change going forward as night lighting increases and temperatures rise is less clear. Temperature and artificial light together influence the fall color in a complex way, and our projections suggested that the delay of coloring date due to climate warming might stop midcentury and possibly reverse because of artificial light. This will require more research.

How urban artificial light will change in the future also remains to be seen.

One study found that urban light at night had increased by about 1.8% per year worldwide from 2012-2016. However, many cities and states are trying to reduce light pollution, including requiring shields to control where the light goes and shifting to LED street lights, which use less energy and have less of an effect on plants than traditional streetlights with longer wavelengths.

Urban plants’ phenology may also be influenced by other factors, such as carbon dioxide and soil moisture. Additionally, the faster increase of temperature at night compared to the daytime could lead to different day-night temperature patterns, which might affect plant phenology in complex ways.

Understanding these interactions between plants and artificial light and temperature will help scientists predict changes in plant processes under a changing climate. Cities are already serving as natural laboratories.

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.