Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

Trump White House discussions about using presidential emergency powers have become an important but little-known part of the panel’s inquiry

The text from Greene (R-Ga.), revealed this week, brought to the fore the chorus of Republicans who were publicly and privately advocating for Trump to try to use the military and defense apparatus of the U.S. government to strong-arm his way past an electoral defeat. Now, discussions involving the Trump White House about using emergency powers have become an important — but little-known — part of the House Jan. 6 committee’s investigation of the 2021 attack on the Capitol.

In subpoenas, document requests and court filings, the panel has demanded information about any Trump administration plans to use presidential emergency powers to invoke martial law or take other steps to overturn the 2020 election.

Interviews with committee members and a review of the panel’s information requests reveals a focus on emergency powers that were being considered by Trump and his allies in several categories: invoking the Insurrection Act, declaring martial law, using presidential powers to justify seizing assets of voting-machine companies, and using the military to require a rerun of the election.

“Trump’s invocation of these emergency powers would have been unprecedented in all of American history,” said J. Michael Luttig, a conservative lawyer and former appeals court judge.

The House Jan. 6 investigation committee has conducted over 800 interviews with insurrectionists and Trump aides. Here’s what’s next. (Video: Blair Guild/The Washington Post)

There is no proof Trump ordered any U.S. official to invoke emergency powers, and many of Trump’s advisers and attorneys say privately they would have balked at such a request. An adviser to former vice president Mike Pence said he was never asked to invoke any emergency powers. But several advisers said that Trump was interested in seizing voting machines and that he did at times suggest that the election should be done over.

Some advisers interviewed for this report spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss sensitive matters. A representative for Trump did not respond to a request for comment.

Trump listened in White House meetings and on phone calls as allies including Sidney Powell, Mike Lindell, Patrick Byrne and Rudy Giuliani stoked baseless conspiracy claims about voting machines and other matters, according to people present for those conversations. At least some of these figures proposed extraordinary measures, and Trump at times seemed to signal his agreement, according to people present.

Trump even suggested Powell should be appointed as special counsel after she proposed some extreme measures, former White House advisers said, and she made several return trips to the building. That notion was eventually scuttled.

“Trump had a lot of emotional people around him,” said Sen. Lindsey O. Graham (R-S.C.), a Trump ally. “You got all these nefarious characters around him pushing him to do things, but it didn’t happen.”

Among the records the panel is examining are memos authored and circulated by Trump allies that centered on using government powers to seize voting machines, as well as text messages showing lawmakers such as Greene and Rep. Scott Perry (R-Pa.) directly lobbying Meadows to invoke extraordinary powers on the basis of false conspiracy claims. As it continues to examine and collect such evidence, the House committee is trying to determine just how seriously Trump considered these proposals, according to a member of the panel.

Meanwhile, the Jan. 6 committee is also looking to suggest changes to emergency-powers statutes that would provide guardrails against abuse going forward.

“I consider it important for us to determine to what extent the president was prepared or preparing to use the Insurrection Act or make use of any other presidential emergency powers,” Rep. Jamie B. Raskin (D-Md.), a member of the committee, told The Washington Post in an interview earlier this year. “We have to look at how the existence of an arsenal of residual presidential emergency powers threatens the traditional peaceful transfer of power in the country.”

The Insurrection Act is an 1807 law that gives a president authority to federalize the National Guard to quell local rebellions, conspiracies and violence, offering a way around legal prohibitions against using military forces to enforce domestic laws.

Some of the president’s backers who were stoking false conspiracy claims presented memos to key members of Congress and other Trump allies, hoping to get Trump’s support. It is unclear whether he ever saw the documents, which included proposals for National Security Agency involvement and extrajudicial control of the government.

“In our private chat with only Members, several are saying the only way to save our Republic is for Trump to call for Marshall law,” Greene texted Meadows on Jan. 17, 2021 — 11 days after the Capitol insurrection. Martial law refers to the temporary military takeover of civilian functions.

The Post confirmed the exchange involving Greene and Meadows, which was first reported by CNN on Monday. Meadows has provided thousands of texts to the Jan. 6 committee.

Representatives for Meadows and the Jan. 6 committee did not respond to a request for comment.

Many have argued that President Donald Trump's efforts amounted to an attempted coup on Jan. 6. Was it? And why does that matter? (Video: Monica Rodman, Sarah Hashemi/The Washington Post)

Testifying publicly under oath last week about the events of Jan. 6, Greene said she could not recall whether or she discussed the invocation of martial law to keep Trump in power.

A representative for Greene did not respond to a request for comment.

Unlike many other countries, the United States does not grant presidents express emergency powers in its Constitution, said Elizabeth Goitein, co-director of the liberty and national security program at New York University Law School’s Brennan Center for Justice.

Instead, presidents rely on several acts of Congress to provide emergency authority. The most sweeping is the National Emergencies Act, a 1976 law that allows a president declare a “national emergency” at will. Trump declared more national emergencies than any president in a four-year period, including one that authorized building a wall along the southern border that Congress had declined to fund.

Trump would often mock advisers or lawyers who told him such moves were illegal. John F. Kelly, the president’s former chief of staff, told other advisers they were wasting their time by telling Trump some of his ideas were against the law. “He doesn’t care,” Kelly said to others, according to a person with direct knowledge of the comments.

These emergency statutes were not intended to allow a president to challenge election results, Goitein said in an interview earlier this year. And the presidential emergency statutes contain fundamental flaws that could lead to abuse, she argued: “It’s important for the January 6 committee to be looking at these things and to be worried about them, because there is room for mischief around an election. You have to worry now about how a president might choose to construe these laws and apply them in a way that takes them even beyond their fairly capacious bounds.”

Goitein also applauded the committee’s interest in looking at discussions of involving martial law.

“Right now, there is no statutory authority for a president to declare martial law, but a president might assert that he or she has an inherent constitutional authority to declare martial law that Congress cannot restrain,” she said.

A week after the Jan. 6 insurrection, a news photographer captured a picture of Lindell, the chief executive of MyPillow, outside the West Wing holding a piece of paper with words including “Insurrection Act now … martial law if necessary.”

Advisers say Trump shrugged off Lindell and sent him to White House lawyers, who were dismissive of Lindell and soon shooed him out of the West Wing. But Lindell has stayed in touch with Trump, and the two have at times discussed Trump’s reinstatement to the presidency, according to advisers.

A committee subpoena to Michael Flynn, who had served as Trump’s national security adviser, requested information about a reported Dec. 18, 2020, meeting in the Oval Office during which “participants discussed seizing voting machines, declaring a national emergency, invoking certain national security emergency powers.”

The subpoena cited an interview Flynn gave to Newsmax the day before in which he talked about “the purported precedent for deploying military troops and declaring martial law to rerun the election.”

Flynn, who appeared before the committee last month and repeatedly cited the Fifth Amendment, did not respond to a request for comment.

Perry, the Pennsylvania Republican, made similar claims in text messages to Meadows, according to records obtained by CNN and independently verified by The Post.

“From an Intel friend: DNI needs to task NSA to immediately seize and begin looking for international far related to Dominion,” Perry wrote to Meadows on Nov. 12, 2020, apparently urging that Director of National Intelligence John Ratcliffe to order the NSA to investigate an unfounded claim that China had hacked into Dominion voting machines.

Perry has declined to cooperate with the House committee’s request for an interview. He told The Post on Wednesday that he was still concerned about election integrity and did not regret sending Meadows those texts.

“I was concerned then as I’m concerned now, as many Americans are, about the integrity of elections, and asking for investigations into claims of fraud is not out of the realm of what’s right for members of Congress to do,” Perry said.

The committee has also focused attention on the Defense Department, from which it sought “all documents and communications relating to the potential use of military power to impede or ensure the peaceful transfer of power between the election and inauguration day,” according to a record requests made by the committee. It also demanded all documents and communications related to “attempts by President Donald Trump to remain in office” after Inauguration Day.

Investigators have interviewed top Pentagon officials — including former acting defense secretary Christopher C. Miller; longtime Trump loyalist Kash Patel, who was appointed as Miller’s chief of staff on Nov. 10, 2020; and former Army secretary Ryan McCarthy — as they piece together a comprehensive account of the role the Defense Department played in responding to the Jan. 6 attack, according to court filings and subpoenas issued over the course of the investigation.

The committee’s request to Patel explicitly requested all communications relating to “the establishment of martial law, requests to establish martial law, or legal analysis of martial law” and “all documents and communications relating to” invoking the Insurrection Act.

“President Trump never had any intention to abuse emergency powers, I was completely open with the committee,” Patel told The Post in a statement. “I have also repeatedly asked the committee to release the transcript from my hearing and look forward to that being shared with the American people.”

Gen. Mark A. Milley, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, was so concerned about the threat of a coup attempt by Trump and his allies that he discussed a plan with his fellow joint chiefs to resign rather than carry out orders from Trump that they viewed as illegal, Post reporters Carol D. Leonnig and Phil Rucker wrote in their book “I Alone Can Fix It.”

Milley, who was concerned about Trump’s rash of personnel moves after the election, “told his staff that he believed Trump was stoking unrest, possibly in hopes of an excuse to invoke the Insurrection Act and call out the military,” according to the book.

Another proposal outlining a plan for Trump to invoke emergency powers surfaced in a committee court filing released last week. Phil Waldron, a retired Army colonel, coordinated with Trump’s outside legal team on a proposal to issue executive orders empowering various government agencies to investigate whether there was foreign interference in the 2020 election. Waldron emailed the plan to Meadows on Dec. 22, 2020, the filing shows.

Waldron previously told The Post he had sent Meadows a list of IP, or Internet protocol, addresses and other targets for investigation after meeting with Meadows at the White House in December 2020. Waldron said Meadows indicated that he would pass the list on to Ratcliffe but said he did not know whether Meadows ultimately did. Through a spokesman, Ratcliffe said he did not receive such a document.

“Reviewing a president’s use of emergency powers is an important aspect of this committee’s mandate,” Richard Ben-Veniste, a Watergate prosecutor, said in an interview earlier this year. He urged the committee to be transparent about what it learns about the discussions that took place in Trump’s White House.

“Democracies are not self-executing perpetual motion machines,” he said. “They require the care and protection of the governed to endure.”

Part of the committee’s emergency-powers inquiry is focused on Jeffrey Clark, former acting head of the Justice Department’s civil division, according to court filings and committee requests. Clark drafted a letter to Georgia officials in December challenging the vote there and made inquiries about using the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) to go after voting-machine companies, according to emails released as a part of a Senate Judiciary Committee report probing the efforts of Trump and his allies to pressure the Justice Department to overturn the results of the 2020 election.

That act is generally used to impose economic sanctions on foreign adversaries but is written so broadly that a president can freeze the U.S. assets of American companies if the president deems it necessary to address a foreign threat.

On Dec. 28, Clark emailed then-acting attorney general Jeffrey Rosen and another Justice Department official, Richard Donoghue, requesting a classified briefing on foreign election interference issues from Ratcliffe, according to the Judiciary Committee report. “I can then assess how that relates to activating the IEEPA and 2018 EO powers on such matters,” Clark wrote in the email, referencing an executive order that Trump signed permitting sanctions in the event of foreign interference in a U.S. election.

Clark cited unsupported evidence “in the public domain” that Dominion voting machines had been hacked through a “smart thermostat with a net connection leading back to China.”

The IEEPA authorizes a president “to declare a national emergency due to ‘unusual and extraordinary threats’ to the United States and to block any transactions and freeze any assets within the jurisdiction of the United States to deal with the threat,” according to the Senate report.

Clark did not respond to a request for comment.

The Insurrection Act has come up frequently in the Jan. 6 committee’s requests for information, in part because it was bandied about by the president’s supporters, including the far-right Proud Boys and others alleged to have instigated violence. Trump also had a history of mentioning it.

The Insurrection Act has been used in moments of civil unrest — the Civil War, desegregation battles, rioting following the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination. Goitein says the law is far too broad, enabling a president to send in armed forces without the consent of a state’s governor.

Sen. Tom Cotton (R-Ark.) raised the idea of using the Insurrection Act in a 2020 New York Times op-ed, calling on Trump to invoke the law in response to civil disturbances after the killing of George Floyd by police in Minneapolis. Trump mentioned using the act to restrain “leftist thugs” that summer.

In September 2020, Trump ally Roger Stone brought it up in an interview with the far-right website Infowars as a way for Trump to combat election fraud, among other things.

In a Newsmax interview on Dec. 19, 2020, Flynn said the president “could take military capabilities, and he could place those in states and basically rerun an election in each of those states.”

And Trump told Fox News host Jeanine Pirro that September that he would “put down” anti-Trump protests “very quickly” if they broke out after the election: “Look, it’s called insurrection. We just send in, and we do it very easy.”

Trump’s interest in emergency powers drew bipartisan calls for change. Sen. Mike Lee (R-Utah) introduced a bill after the election that would terminate any presidential emergency declaration under the National Emergencies Act after 30 days — unless Congress voted to extend it for one year.

Trump’s expressed interest in mobilizing the military after the election prompted Pentagon leaders to speak out before and after the election.

“This isn’t the first time that someone has suggested that there might be a contested election,” Milley told NPR in mid-October 2020. “And if there is, it’ll be handled appropriately by the courts and by the U.S. Congress. There’s no role for the U.S. military in determining the outcome of a U.S. election. Zero. There is no role there.”

The funding would include $20 billion in military and security assistance, including weapons and ammunition for Ukraine and its allies in the region. (photo: Anatolii Stepanov/Getty)

The funding would include $20 billion in military and security assistance, including weapons and ammunition for Ukraine and its allies in the region. (photo: Anatolii Stepanov/Getty)

Abortion-rights activists supporting legal access to abortion protest outside the U.S. Supreme Court, March 4, 2020. (photo: Saul Loeb/Getty)

Abortion-rights activists supporting legal access to abortion protest outside the U.S. Supreme Court, March 4, 2020. (photo: Saul Loeb/Getty)

Val Broeksmit supplied the documents to journalists and others, including Fusion GPS, the research firm linked to an unverified dossier about Trump. (photo: Mat Szwajkos/Getty)

Val Broeksmit supplied the documents to journalists and others, including Fusion GPS, the research firm linked to an unverified dossier about Trump. (photo: Mat Szwajkos/Getty)

"We had a complicated relationship, but this is just devastating to hear,” a journalist who described him as a longtime source said.

The body of Valentin Broeksmit, 46, was found Monday at Woodrow Wilson High School shortly before 7 a.m., Sgt. Rudy Perez of the Los Angeles School Police Department said in an email.

Records of the Los Angeles County Medical Examiner-Coroner do not list a cause of death. Los Angeles Police Capt. Kenneth Cabrera told the Los Angeles Times that authorities do not suspect foul play.

Broeksmit was last seen driving a red Mini Cooper on the afternoon of April 6, 2021, on Riverside Drive and was later reported missing by relatives, Los Angeles police said.

His vehicle was found, the department said, but Broeksmit remained missing.

Perez said Wednesday that he appeared to be homeless.

According to a 2019 profile in The New York Times, Broeksmit was a musician and the son of a Deutsche Bank executive who died by suicide in 2014.

After his father's death, Broeksmit gained access to his father's email account and found hundreds of files related to the bank, including board meeting minutes, financial plans, spreadsheets and password-protected presentations, the newspaper reported.

Federal and state authorities were scrutinizing allegations of criminal misconduct and the bank's long relationship with former President Donald Trump, the newspaper reported.

According to The Times, Broeksmit supplied the documents to journalists and others, including Fusion GPS, the research firm linked to an unverified dossier about Trump, and investigators with the FBI's New York office.

After a meeting with FBI agents in Los Angeles, the agency permitted Broeksmit to publicly identify himself as a cooperating witness in a federal criminal investigation, the paper reported.

Neither Fusion GPS nor the FBI immediately responded to requests for comment.

David Enrich, the Times reporter who wrote the profile, said Tuesday on Twitter that Broeksmit was a central character in his 2020 book, "Dark Towers: Deutsche Bank, Donald Trump, and an Epic Trail of Destruction," and that news of his death was "terrible."

"We had a complicated relationship, but this is just devastating to hear," he said.

A latent fingerprints analyst demonstrates his process during a tour of the Department of Forensic Science in northern Virginia. (photo: Getty)

A latent fingerprints analyst demonstrates his process during a tour of the Department of Forensic Science in northern Virginia. (photo: Getty)

Charles McCrory has spent decades in prison for the murder of his wife, convicted on the strength of bite mark evidence. The problem? CSI-style forensics is bad science

What haunts him is the look on the jurors’ faces as they listened to the testimony of the prosecution’s star witness, a dentist named Richard Souviron. He was a founding father of a cutting-edge branch of forensic science known as bite-mark analysis, which claimed to be able to identify violent criminals by matching their unique dental patterns to the bite wounds on victims’ bodies.

McCrory was expecting Souviron’s evidence to be nuanced. In his initial report, the dentist had been cautious about what could be deduced from two puncture marks found on the upper right arm of Julie’s body, saying that the injuries were insufficiently distinct to allow a positive match with the perpetrator.

But that was not what he told the jury.

When Souviron was asked whether the two marks were teeth marks, he said: “Yes.”

Then the prosecutor asked him: “In your expert opinion, based on the evidence presented to you, were these teeth marks made by Charles McCrory?”

“Yes,” the dentist replied.

McCrory remembers vividly the sinking feeling he experienced in that moment, given the glaring contrast between Souviron’s initial report and what he was now saying in court. “I was in disbelief at his testimony being so different,” he recalled. “I knew it was extremely damaging to our case. You could see it in the eyes of the jurors.”

McCrory shared his recollections of that critical instant in a handwritten letter he sent to the Guardian earlier this month.

It was composed from an Alabama prison cell where he is serving a life sentence, still protesting his innocence, 37 years after the jury returned a guilty verdict based on that one simple word: “Yes.”

McCrory’s current lawyer is Chris Fabricant. Together with co-counsel, Mark Loudon-Brown, Fabricant is representing the prisoner in an epic battle to clear his name almost four decades after he was identified as the source of those supposed teeth marks on his wife’s body.

For Fabricant, this is much more than a routine criminal case. It is the latest chapter in a personal voyage that began 10 years ago, when he embarked on his exploration of the murky waters of forensic science.

Fabricant is director of strategic litigation at the Innocence Project, the formidable New York-based non-profit that for 30 years has used DNA evidence to overturn hundreds of wrongful convictions. He is an authority on the perils and limitations of science as it has been applied to criminal justice.

In that role, he has become one of forensic science’s most piercing critics. He has highlighted the part played by “expert witnesses” – forensic dentists, ballistics experts, FBI laboratory agents, lie detector examiners, blood stain investigators – in inadvertently putting innocent people behind bars.

He has a word for it: junk science.

In his new book, Junk Science and the American Criminal Justice System, Fabricant explains what he means by the term. “Junk science sounds like science,” he writes, “but there is no empirical base for the ‘expert opinion’; it is subjective speculation masquerading as science.”

The world of junk science took off in the late 1960s and 70s – an era in which confidence about the ability of scientists to propel humanity to giddy new heights was unbound. If science could put a man on the moon, then surely it could do the much more mundane job of nailing violent criminals?

Fabricant told the Guardian that there were problems with the new forensic science techniques from their inception. The methods did not arise out of the usual scientific method that starts with a problem, develops an hypothesis to solve it, then tests it via empirical methods.

Rather, it turned the formula on its head. Start with a desired solution – banging up criminals – then work back to the science that would support it.

“Most of the new theories emerged not from a scientific laboratory but from a crime scene,” Fabricant explained. “An enterprising investigator would think, ‘Maybe I could match this suspect’s teeth to the bite on this victim’s nose – that would prove the suspect is the murderer’. Then off they’d go and find an expert witness who could back the theory up.”

The explosion in junk science began with forensic pathologists who, with the enthusiastic encouragement of the FBI’s legendary crime laboratory, began to invent a plethora of new forensic practices.

The new generation of techniques had this in common: they all claimed to be able to identify an individual perpetrator through forensic analysis of various types of crime scene evidence.

There was “hair microscopy” – the idea that a single hair retrieved from the scene of a murder could be put under the microscope and matched with high degrees of certainty to the suspect’s hair. There were lie detector tests sold under the portentous title “polygraphs”; voice spectrometry to identify a criminal through forensic deconstruction of their speech; “toolmark” analysis that sought to link marks found at a crime scene to a specific object – a pipe, perhaps, or hammer; and comparative bullet lead analysis that professed to be able to match a bullet found at the scene of a killing to the single box of bullets from which it originated.

As use of the new techniques began to spread across the US, the reputation of forensic pathologists soared. They were invited to attend specialist conferences around the world, and lauded as “medical detectives”.

Celebrity status wasn’t far behind. One of the earliest stars of the genre, New York’s medical examiner Dr Milton Helpern, was called “Sherlock Holmes with a microscope”.

His successor, Dr Michael Baden, was given his own HBO TV series in the 1970s. Autopsy showcased a new forensic technique each week, highlighting the wonders they performed in solving gruesome and knotty crimes. Baden later went on to be involved in high-profile cases such as the OJ Simpson trial and the autopsy of Michael Brown, the unarmed Black teenager shot dead by a police officer in Ferguson, Missouri.

Following the rise of such celebrities, it was but a step to forensic science becoming infused into the popular imagination. TV shows that had lionized vice cops and FBI special agents now began to switch their soft-focus lenses on to forensic pathologists.

Forensic Files aired from 1996 to 2005. CSI: Crime Scene Investigation, a formidably popular show aired between 2000 and 2015, looked at how forensic scientists cracked the hardest criminal cases. Once this glowing view of forensics had taken hold of the small screen, it was inevitable that it would seep into the mindset of juries.

“These TV shows depict an unrealistic infallibility of forensic sciences which became part of our popular culture,” Fabricant said. “Jurors walk into court believing that if it is forensic science that ties this defendant to the crime, then the likelihood of their guilt is overwhelming.”

With forensic pathologists soaking up so much glamorous TV coverage, it was only a matter of time before dentists wanted in on the game. By the late 1970s, as Fabricant chronicles in his book, “forensic odontology” was starting to emerge, pioneered by a small number of individuals who were portrayed as “swashbuckling crime fighters, handsome, fit, bawdy, prone to ghoulish humor, comfortable with dead bodies, brilliant. Men’s men.”

Fabricant quotes the Los Angeles Times remarking admiringly that one of those pioneers, Dr Gerald Vale, hadn’t fixed a tooth in years. “His job is to fill jail cells, not cavities,” the paper gushed. An industry newsletter said about Vale: “Instead of tracking down decay, he tracks down people!”

What united the group of 12 “founding fathers” of forensic odontology was the belief that bite mark evidence could be used as a new tool up there with fingerprints, toxicology and other established methods. But to be taken seriously, the pioneers needed to establish their reputation, and for that they needed to be recognized as a scientific specialism as worthy of respect as any pathologist.

They began in 1976 by forming an “odontology section” within America’s top professional forensics body, the American Academy of Forensic Sciences. Not content with playing second fiddle, they then created their own organization, the American Board of Forensic Odontology (ABFO). As icing on the cake, they granted themselves a fancy title: “diplomates”, they called themselves, signaling their specialist status as trained and authoritative experts.

So when Souviron travelled the country to appear as a star expert witness in criminal cases such as McCrory’s murder trial, he did so not as Richard Souviron, dentist from Florida, but as Dr Richard Souviron, board-certified diplomate and member of the ABFO.

How could a jury resist that?

“This was 1985, when to fly an ‘expert’ witness in from Florida was practically unheard of,” McCrory wrote in his letter to the Guardian, referring to his own trial. “No jury, as lay people, have the ability to genuinely question a supposed expert, especially back then.”

The problem was, bite mark analysis, like many of the new forensic techniques, was founded upon so much hot air. There are two stages involved in matching a wound to an individual perpetrator, and both of them are flakey.

The first is categorically to confirm that the wound is caused by someone’s teeth and not by some other sharp object. The second stage is to link the alleged bite mark to the dental pattern of the suspect, by taking a mould of the suspect’s teeth and comparing it to the wound.

Analysis in both those stages, contrary to the scientific method, is subjective. A study published in 2009 by New York scientists tested whether skin could accurately record the impressions left by teeth – the 3D-equivalent of a fingerprint – and found that it could not.

The scientists simulated 23 identical bites on a single piece of un-embalmed cadaver skin. They discovered that the bites produced 23 entirely different marks, each one bearing little resemblance to the rest.

A more detailed study in 2015, carried out by ABFO-certified forensic dentists themselves, asked 38 of their fellow “diplomates” to review photographs presented in real criminal cases where bite mark analysis had been used. Of the 100 cases they examined, the analysts reached unanimous agreement in only four.

These two experiments effectively toppled the entire house of cards upon which bite mark analysis had been erected.

In his book, Fabricant concludes that when forensic dentists presented juries with a “near certain” match between the marks on a victim and a suspect – as Souviron did at McCrory’s trial – all they were doing was expressing their own personal opinion.

It is a paradox that it took science to overcome junk science. “Nothing else could have challenged it other than DNA evidence, because a clean DNA sample is indisputable,” Fabricant said. “DNA was like a truth serum that the justice system had never before been exposed to.”

Over the years, DNA analysis has demonstrated itself to be blessed with all the qualities that junk science claims to enjoy but lacks: reliability, certainty, accuracy, indisputability.

The DNA revolution was launched in 1992 when two young lawyers in New York City decided to take on the combined might of the criminal justice system just as it was getting into its mass incarceration stride.

Barry Sheck and Peter Neufeld founded the Innocence Project to take on cases where crime scene evidence allowed DNA testing to be carried out. They used it to expose wrongful convictions and secure exonerations – more than 200 to date attained by the Innocence Project alone.

As time passed, the group’s crack team of lawyers observed that in so many of the wrongful convictions, the prosecution had relied upon the testimony of forensic scientists. Almost half of the total of 375 exonerations that have been achieved by the Innocence Project and other groups using DNA evidence involved the misuse of forensic sciences.

The dawning realization that junk science might have put a vast mountain of innocent people behind bars has inspired the Innocence Project to make a historic revision of its mission.

As it approaches its 30th anniversary this year, the organization has decided to widen the net of cases that it takes on to include those where no DNA evidence is available.

That’s a big change in focus. Up to now, the Innocent Project has pinpointed its energies almost exclusively on DNA. But what about people who cannot call on DNA to prove their innocence, maybe because there were insufficient crime scene materials, or maybe because such materials were destroyed post-trial? Are those people to be abandoned with little hope of ever receiving justice?

“Those who can be exonerated with DNA evidence represent just the tip of the iceberg,” Christina Swarns, the executive director of the Innocence Project, told the Guardian. “Going forward, the Innocence Project will begin to accept non-DNA cases and we will approach them with the same tenacity, innovation and client-centered approach we brought to our DNA work.”

This is a significant paradigm shift for an organization that put the concept of wrongful conviction on the map, both in the United States and around the world. By widening its focus to include non-DNA cases, Fabricant believes it will herald “a new era of innocence litigation that will involve undoing the legacy of junk science”.

Which prompts the question: how many innocent people are out there?

“I shudder to think,” Fabricant said. “There are 2.3 million people incarcerated in this country. Even if the wrongful conviction rate were 1% , and that’s conservative, you are looking at tens of thousands of people.”

Fabricant is convinced that McCrory, who is now 62, is one of them. “Mr McCrory is obviously innocent, and he would be out right now if we had DNA evidence.”

Julie Bonds was murdered on 31 May 1985 in her home in Andalusia, south Alabama. McCrory was not living in the house at the time – the couple had recently separated after 10 years of marriage; they had one son together.

McCrory and his father discovered her body after they called on the house, worried that she was not answering the phone. She had been badly beaten, and had a deep wound to her skull.

The 1985 McCrory trial was held just before DNA analysis came on stream – the first time DNA was used to convict someone was in Florida in 1987, while the first DNA exoneration followed two years later in Chicago.

Because it was presumed to serve no further useful purpose, all the crime scene materials collected in the Bonds murder investigation were destroyed – a routine event in pre-DNA days. That left no biological samples to test once DNA was commonplace.

Detectives investigating the Bonds murder actually found hairs clutched in the hand of McCrory’s murdered wife that conventional examinations conducted at the time ruled out as having come from him. But the hairs, along with everything else, were binned.

Other evidence also pointed to McCrory’s innocence. At the time of Bonds’ killing, a construction worker was being employed on a building project in the house next door. He wore a red bandana.

Five weeks after Julie Bonds was murdered, that same man was arrested for breaking into a different home and raping the owner. He served 20 years in prison. At that crime scene, officers found a red bandana.

Despite the inconsistencies in his case, McCrory was at a powerful disadvantage. Without the benefit of DNA to clear his name, he languished in prison for decades.

Meanwhile, however, bitemark analysis was beginning to unravel.

In 2009 – by which time McCrory had spent 24 years in prison – the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) released a 300-page report on the use of forensic science that sent what Fabricant called a “thunderbolt” across the criminal justice system.

It was searingly critical of 13 forensic techniques that were routinely being used in criminal trials. It reserved its most scathing denunciation for bitemark analysis.

The report’s authors noted that the claim that dentists could positively identify a perpetrator by matching their dental patterns to marks on victims’ bodies had never been supported by any scientific study. Indeed, “no large population studies have been conducted”.

In other words, bitemark analysis was an unsubstantiated whim on the part of its inventors. The report concluded that there was “no evidence of an existing scientific basis for identifying an individual to the exclusion of all others”.

The combined impact of the NAS report and DNA evidence led to a renewed focus on criminal cases where bitemark analysis had been critical to the prosecution. Scientific certainty began to crumble. Exonerations mounted up.

Today, the tally of people who have been exonerated after wrongful indictment or conviction involving bitemark analysis stands at 35.

They include several of Fabricant’s clients: Keith Allen Harward, exonerated in 2016 after spending 33 years in prison for a rape and murder he did not commit; Stephen Chaney, exonerated in 2019 after 28 years behind bars; Eddie Lee Howard, exonerated in 2020 – 26 years inside.

They were the lucky ones.

David Wayne Spence was convicted of murdering three teenagers in 1982 after his teeth were matched to bite marks on the victims’ bodies. On 3 April 1997, he was strapped to a gurney and lethal drugs injected into his veins.

He went to his death insisting he was innocent.

In December 2019, Souviron recanted his testimony. He had taken another look at the evidence in the case, considered it alongside the criticisms raised by the NAS report, and went on the record to say he had been wrong.

“While this testimony was understood by myself and others within my field as scientifically acceptable at the time of trial, I would not give [it] today,” he said in an affidavit. “As a forensic odontologist I no longer believe the individualised teeth marks comparison testimony I offered in his case was reliable or proper. I therefore renounce that testimony.”

The Guardian reached out to Souviron to ask him how he came to change his thinking so radically, but his office said he was not available.

The dentist’s reversal was sweet music to McCrory’s ears. “We knew a recantation from the state’s own witness, their only forensic witness, would eviscerate their case. At that point the only fair way forward would be a new trial,” the prisoner wrote.

McCrory duly petitioned for a new trial. With no forensic evidence of any sort, and with no other substantive evidence to rely upon, the state’s tank was running on empty. Even the prosecutors admitted that McCrory posed no harm to the public.

In April last year, on the eve of a court hearing to determine whether a new trial should be granted, the prisoner was offered a plea deal.

He could walk free, that very same day, on one condition. He had to plead guilty to his wife’s murder.

He declined the deal, opting to stay in his cell.

“That was an easy decision,” he wrote in his letter to the Guardian. “I did not murder her … I didn’t do it, and I’m not admitting to it.”

He added: “Someone murdered Julie. Someone knows who it is. We are seeking the truth, not falsely confessing to a crime I didn’t commit.”

Many people would find McCrory’s rejection of a deal that would have instantly set him free hard to comprehend. Fabricant is among them.

“I can understand it in an intellectual way, but as a human being I think after 36 years I’d want to go home,” he said.

McCrory still hasn’t gone home. It has now been 37 years and counting. The bitemark case against him has been thoroughly debunked, but it turns out that doesn’t matter. Junk science proves to be scarily resilient – an invasive weed that grows rampant across the country, poisoning the criminal justice system as it spreads.

A few days after McCrory turned down the plea deal, an evidentiary hearing was held in front of Judge Charles Short in Andalusia, Alabama, to discuss the request for a new trial.

Souviron’s recantation was presented to the court, as was the testimony of three other forensic dentists who not only confirmed that the marks on Julie Bond’s body could not be matched to the prisoner, they said that the marks were not even caused by teeth in the first place.

Judge Short listened to this devastating argument, took in all the other evidence of McCrory’s innocence, then issued his ruling: there would be no new trial; McCrory would remain in prison.

Fabricant was uncharacteristically lost for words when he tried to describe his reaction to the judgment. “How can that be? How can that be? It’s preposterous. We are in 2022 and a judge is refusing a new trial even when the scientist in question has recanted. He is keeping an innocent man in prison based on nothing.”

Despite the knock-back, McCrory says he is keeping his spirits up. “I’m optimistic that justice will prevail,” he wrote at the end of his letter. “Every time we have run into a seemingly dead-end, a door has opened. We will not stop until we have the truth.”

This will be scant comfort to McCrory, but he is not alone. Fabricant points out that bitemark analysis is still admissible in all 50 states of the union.

Three of the most influential bitemark cases where marks were matched to “guilty” perpetrators have all ended in exonerations. Yet the cases retain their status as “good law” and continue to be cited as precedent in court to this day.

In the wider world of junk science, not only do discredited techniques continue to be used, but new techniques keep popping up. Fabricant rattles off three examples of forensic innovations that are beginning to ring alarm bells.

There’s forensic podiatry, where foot doctors claim they can identify a perpetrator from their gait; cadaver dogs which are supposedly able to sniff out the presence of a human corps even years after the body may have been present; and ShotSpotter, an audio system that purports to be able to isolate the sound of gun shots from other noise in urban areas.

If that all sounds depressingly familiar, that’s because it is.

“Our goal in the Innocence Project is to go out of business – we aspire to become unnecessary,” Fabricant said. “It appears we are going to be around for a very long time to come.”

Gustavo Petro in Bogota, Colombia, 12/4/2019. (photo: Gabriel Leonardo Guerrero/Shutterstock)

Gustavo Petro in Bogota, Colombia, 12/4/2019. (photo: Gabriel Leonardo Guerrero/Shutterstock)

Farming cattle, largely for beef, is the No. 1 driver of deforestation. Here, cattle graze in a deforested area in the Colombian Amazon, November 4, 2021. (photo: Raul Arboleda/Getty)

Farming cattle, largely for beef, is the No. 1 driver of deforestation. Here, cattle graze in a deforested area in the Colombian Amazon, November 4, 2021. (photo: Raul Arboleda/Getty)

Just one country was responsible for more than a third of all deforestation in the tropics.

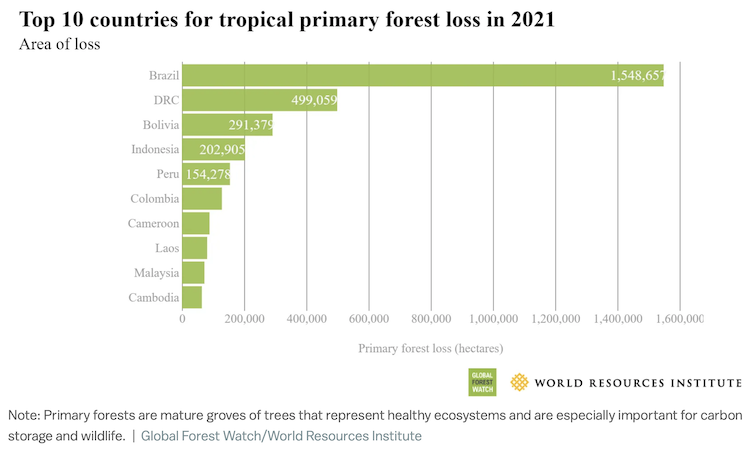

In the tropics, where nearly all deforestation takes place, farming, logging, and wildfires destroyed more than 11.1 million hectares (27 million acres) of trees last year, an area roughly the size of Virginia, according to a new analysis by the nonprofit World Resources Institute (WRI). More than a third of that loss was in tropical “primary” rainforests — old and unharmed groves of trees that store huge quantities of carbon, which is now likely to reenter the atmosphere where it will fuel climate change.

These losses extended to areas outside the tropics as well. In Russia, home to the largest forested area on Earth, wildfires wiped out more than 6.5 million hectares (16 million acres) of boreal, or snow, forest in 2021, roughly equivalent to the area of West Virginia, WRI’s analysis shows. (The organization typically doesn’t consider these losses “deforestation” because forests may grow back after a wildfire.)

Losing two states’ worth of forests in a single year is alarming but not unusual. Compared to 2021, the tropics lost slightly more primary forest in 2020. What’s surprising is that rampant deforestation continues, seemingly unbridled, even as companies and countries promise to save these ecosystems, which people and animals depend on. What’s more, just a few places — and a few products — are behind the bulk of this destruction.

Just one country is responsible for more than a third of all deforestation in the tropics

More than 40 percent of the primary forests that humans wiped from the tropics last year were in Brazil, according to WRI’s analysis. Most of that loss was in the Amazon, the largest rainforest on Earth.

Deforestation like this often appears in satellite imagery as large shapes cut from dark green expanses, typically near roads. The images below, taken last spring, show deforestation in Mato Grosso, Brazil.

Continuing to cut down the Amazon comes at a staggering cost. It’s weakening the forest and pushing it closer to a dangerous tipping point, some scientists fear, beyond which much of it could turn into a grassy savanna — that is, an entirely different ecosystem.

“Such losses are a disaster for the climate, they’re a disaster for biodiversity, they’re a disaster for Indigenous people,” Frances Seymour, a researcher at WRI, said on a call with reporters, speaking about deforestation in Brazil. (Hundreds of Indigenous tribes live in the Amazon.)

WRI’s analysis also showed steep losses in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), home to the world’s second-largest rainforest. The Congo Basin is not as famous as the Amazon but is no less important, providing habitat for countless endangered animals like chimpanzees and African forest elephants and a home to more than 100 distinct ethnic groups.

But there are some glimmers of good news in the report. Once rampant, deforestation in Indonesia continues to decline thanks to strong corporate pledges and policies, according to WRI. In 2021, it dropped for the fifth straight year, the group said, falling by 25 percent compared to 2020. (However, the price of oil palm, a crop linked to deforestation in Indonesia, is currently at a 40-year high, WRI said. That could put pressure on the industry to chop down more forest for plantations.)

The greatest threat to our forests

It’s not toilet paper or hardwood floors or even palm oil. It’s beef.

Clearing trees for cattle is the leading driver of deforestation, by a long shot. It causes more than double the deforestation that’s linked to soy, oil palm, and wood products combined, according to the World Wildlife Fund.

And worldwide beef consumption is increasing. In 1990, the world ate roughly 48 billion kilograms of beef (and veal); in 2019, consumption surpassed 70 billion kilograms (154 billion pounds), according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Much of the beef-fueled deforestation is in Brazil, followed by Paraguay. Companies that raise cattle are responsible for an astonishing 80 percent of the forest loss in the Amazon, scientists estimate.

Oil palm production is a problem, too, but many of the companies that sell it have committed to preventing forest loss; those pledges are less common among corporations that buy and sell cattle and beef, according to a 2016 report by the nonprofit Forest Trends.

“The disparity is alarming,” wrote the authors of the report, who mention that cattle farming causes an estimated 10 times more deforestation than oil palm.

Can the world actually stop deforestation by 2030?

Advocates have tried to before.

At a UN climate summit in 2014, dozens of governments signed a pact called the New York Declaration on Forests, which aimed to end deforestation by 2030. So far, it hasn’t done much.

Last year, a much larger group of global leaders made a similar pledge at the big climate conference in Glasgow, Scotland. Will this time be different?

“We have had many declarations before and nothing has changed,” Kimaren ole Riamit, an Indigenous leader in Kenya, told Vox last year. “There’s very little to inspire us.”

But some forest scientists and advocates are still hopeful. Last year’s pledge involves a large number of economic powerhouses, including China, and a lot of money. Countries and private institutions backed the commitment with more than $19 billion, which will help poorer nations restore damaged forests and prevent wildfires.

There are other positive signals, too, such as what’s happening in Indonesia. And more than ever, major agencies that shape environmental policies are beginning to incorporate the rights and contributions of Indigenous people and local communities. (It remains to be seen whether support for Indigenous groups extends beyond acknowledging them on paper, advocates caution.)

Getting beef consumption to decrease is a bit trickier, but there’s been some progress. Fast food joints including Burger King and TGI Fridays are now serving plant-based burgers, for example, and the alternative meat sector is beginning to receive government funding.

Ultimately, companies and politicians are responsible for ending deforestation, but that doesn’t mean individuals can’t help. Eating less beef (and other meats) is perhaps the best way to limit your impact on the planet.

Special Coverage: Ukraine, A Historic Resistance

READ MORE

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.