Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

"Endless drip" of Supreme Court dealings "underscores the need for reform," group says

Just months after she was sworn in at the Supreme Court in 2020, Barrett, who had left her judgeship and job as a Notre Dame law professor, sold her private home in South Bend, Indiana, to a recently hired Notre Dame professor who was assuming a leadership role at the Religious Liberty Initiative, according to records discovered by the left-leaning non-profit watchdog group Accountable.US.

The initiative's legal clinic has curried favor with the Supreme Court since its founding in 2020 and filed at least nine "friend-of-the-court" amicus briefs in religious liberty cases before the Court. Alito joined the majority in deciding in favor of the initiative's conservative positions in several of those cases, including the one that reversed Roe v. Wade, and others on issues of school prayer and COVID-19 restrictions on churches.

Neither Barrett's real estate transaction nor Alito's trip to Italy to deliver a keynote at a gala violated the court's ethics rules, several experts told CNN.

"It raises a question – not so much of corruption as such, but of whether disclosures, our current system of disclosures, is adequate to the task," Kathleen Clark, a professor at Washington University in St. Louis Law School who specializes in government ethics, told the outlet.

Barrett sold the home to Brendan Wilson, then a Washington D.C.-based lawyer, for $905,000, a transaction that she was not required to disclose on her annual financial forms. Federal regulations exclude sales of the "personal residence of the filer and the filer's spouse" from financial matters judges are mandated to disclose.

However, some experts told CNN that Wilson's role at the Religious Liberty Initiative and the work of its legal clinic provide another reason why some rules at the Supreme Court should be adapted to increase transparency for the public, giving it a better understanding of the ties between the justices and legal advocates in the high court.

"The court, frankly, it faces a kind of legitimacy crisis because of the really dire weaknesses of its ethics," Clark said. "It has the opportunity to address that legitimacy crisis by, you know, stepping up its ethics game – imposing on itself and then abiding by additional disclosure operations."

Stephanie Barclay, the Religious Liberty Initiative's director, emphasized to CNN that Wilson "really could not be further removed from Supreme Court litigation" and explained that many people involved with the group contribute to the briefs they submit to the Supreme Court.

Wilson's biography on the initiative's page says his role covers "the transactional component of the Religious Liberty Clinic," and a recent job posting from the group specified that the transactional component includes legal advising for religiously affiliated organizations.

Wilson did not respond to CNN's interview requests, nor did Barrett respond to the network's request for comment.

Barrett's real estate transaction makes her the third member of the Supreme Court to have made money from property sales with powerful conservative figures or people connected to legal advocacy groups writing the Court.

Politico reported that Justice Neil Gorsuch sold a vacation home to the CEO of a major law firm who has argued before the court and did not disclose the buyer's name. Justice Clarence Thomas also came under fire earlier this year when ProPublica revealed a 2014 real estate deal he made with GOP megadonor and billionaire Harlan Crow and failed to disclose. The outlet also revealed that Crow had financed decades of lavish travel and gifts for Thomas and paid the tuition of Thomas' grandnephew for two years in the 2000s.

Indiana University law professor and legal ethics expert Charles Geyh told CNN that despite Barrett's transaction falling within Supreme Court regulations, it only further complicates the perception of the court in the public eye.

"It is addressed by the court being much more vigilant in guarding against perception problems created by (the justices') financial wheelings and dealings and going the extra mile to make sure that they not only are clean, but look clean," he said.

The controversies and increased public scrutiny of the court have also sparked calls for a defined code of ethics to be imposed and enforced on the justices.

"The endless drip of shady and corrupt Supreme Court dealings just further underscores the need for reform." Accountable.US President Kyle Herrig said in a statement. "Every federal judge is bound to an ethics code requiring them to avoid behavior that so much as looks improper, except for Supreme Court justices. Chief Justice (John) Roberts has the power to change that, but so far he hasn't shown the courage. If he fails to do his job, Congress must do theirs."

READ MORE  Created in the early 2010s, Wagner Group is a paramilitary mercenary group composed mostly of former Russian military personnel that trains local forces, conducts combat advising, and provides direct-action services. (photo: Creative Commons)

Created in the early 2010s, Wagner Group is a paramilitary mercenary group composed mostly of former Russian military personnel that trains local forces, conducts combat advising, and provides direct-action services. (photo: Creative Commons)

ALSO SEE: Prigozhin, the Mercenary Chief Urging

an Uprising Against Russia's Generals, Has Long Ties to Putin

The mercenaries’ leader, Yevgeny Prigozhin, was once close to the Russian president. Now he is a major threat

The Russian president, Vladimir Putin, has accused Prigozhin of treason and vowed to “neutralise” the uprising.

Who is Yevgeny Prigozhin?

The man now raising a force against Moscow is a former convict and hotdog seller, notorious for his ruthlessness, violence and cruelty.

Born in St Petersburg in 1961, he went to a sporting academy but fell in with petty criminals. Convicted of several violent robberies in 1980, he spent most of his 20s in jail.

Released in 1990 as the Soviet Union was in its death throes, he made his first modest fortune with a fast food stand, but soon had a stake in a supermarket chain, one of the best restaurants in his home city, and the ear and trust of powerful figures, including one Vladimir Putin.

Prigozhin spent more than a decade doing the catering for high-profile official events – photos show him serving Prince Charles and George Bush among others – and building up to oligarch levels of wealth through government catering contracts and other deals.

The seeds of the current insurrection were sown nearly a decade ago when Russia illegally annexed the Crimean peninsula and sent proxy forces into eastern Ukraine. Prigozhin then founded the Wagner mercenary group, which gave Putin a tool for more active military intervention and some degree of plausible deniability.

Prigozhin also set up an army of keyboard trolls, and was indicted in the US for interfering – through his digital warriors – in the 2016 election that brought Trump to power.

Until last year, Prigozhin sued journalists who linked him to these activities, and insisted he only worked in catering and hospitality.

How did he create a private army?

Prigozhin built Wagner into a powerful force over years of interventions across Africa, the Middle East and more recently Ukraine. Syria was the first place Prigozhin’s men established themselves as a formidable fighting force, playing a prominent, if often unacknowledged, role in Moscow’s support of Bashar al-Assad.

They set a pattern which would play out again in Ukraine, operating with impunity, accused of numerous war crimes and taking heavy losses, under commanders not afraid to sacrifice their men.

Wagner troops later fought across Africa, on missions that favoured Russian interests, including in Mali, the Central African Republic and Sudan. He was allowed to recruit in prisons last year, swelling the ranks of his soldiers to about 50,000 men, according to western intelligence analysts.

What resources and support does he have now?

Prigozhin’s character and way of operating stoked tensions with Russia’s conventional military for years, but the feud deepened in recent months.

He launched public broadsides accusing top generals of starving his troops of ammunition and other supplies, and leaving them to die. One video was recorded against a gruesome backdrop of dozens of corpses of Wagner fighters.

His fighters’ crucial combat role in Ukraine, especially in the grinding battle for Bakhmut, means they have supplies of weapons and armoured vehicles.

Some are moving towards Moscow in a column that could be vulnerable to air attacks, though video from the ground apparently shows them deploying air defences.

It is unlikely Wagner’s fighters, for all their experience and discipline, could hold out indefinitely against the full might of the Russian military.

Prigozhin, who does have better ties with some generals, is probably hoping for defections, or perhaps for those worn down by corruption and other failings to stay on the sidelines as he fights it out with his enemies.

What does this mean for Ukraine?

It is impossible to know how this showdown will play out. But whether Prigozhin prevails or fails – most experts think failure is more likely – the fighting is likely to benefit Ukraine.

Focus, weapons and troops are all being shifted away from the frontlines, as Kyiv intensifies its counter-offensive. Prigozhin has said he doesn’t want the war effort to suffer, but Russia’s generals will be forced – at least for now – to concentrate on events at home, even if fighting is limited.

And with Chechen troops reportedly already on their way towards Rostov, where Wagner men have seized military headquarters, any battles in the area will consume lives, weaponry and time.

Whoever ends up in control in Moscow will have to shore up power and authority at home, while trying to fight in Ukraine.

What does it mean beyond Ukraine?

Wagner has been a useful tool of Russian foreign policy and power projection, its troops supporting allies, and providing a warning to those not heeding messages from Moscow.

It is unlikely that Putin can immediately replace this arm’s-length mercenary force, even if he choses to ignore messages from this uprising. The leaders who relied on Wagner support are likely to be reassessing their security.

READ MORE  A doctor and patient. (photo: Rawpixel)

A doctor and patient. (photo: Rawpixel)

It was positive.

“I cried, I cried, I cried,” Lationna says. “It was a surprise. Lord, it was a surprise.” She later figured out she was three months along.

Lationna’s face, framed by hair that hangs in long, soft curls, is round and pretty. Her cocoa skin glows and her large eyes, hidden behind thick glasses, are the same golden shade. She doesn’t smile often, but when she does, it spreads across her whole face, revealing a tiny piercing above her front teeth. At 26, she already had a 4-year-old son, Royalty, tall and skinny with his mom’s coloring and wide eyes. Lationna wanted to give Royalty a sibling someday, so he would be less lonely. But not like this.

Before having another child, Lationna wanted to be married to her partner, Kendall; to have a steady job that paid well; to get a new car; to live in a house instead of an apartment; and for Royalty to be in a better school.

Instead, Lationna worked as an IT clerk at a nearby elementary school, doing things like creating attendance reports and report cards. She liked the job well enough; her coworkers and the students made it worthwhile. But Lationna only earned $8.50 an hour. Her monthly check went immediately to covering rent — $853 a month for a two-bedroom apartment in a complex of dozens of identical buildings in West Jackson, Miss. — plus the internet bill. She lived with Kendall and the two shared expenses. Kendall earned $18 an hour as a welder and detailed cars on the side, but the two still struggled to put money away for savings or emergencies. They couldn’t afford cable; after rent, Lationna barely had enough money to gas up her car.

Lationna hoped to move as soon as they could afford it. The drive to the apartment winds along a road so full of deep, wide potholes that drivers have to swerve into the oncoming lane to spare their tires. Jackson’s water treatment facility failed in August 2022, leaving the city without clean water for weeks. Problems bubbled up again late that December, all connected to Mississippi’s decades-long underfunding of critical infrastructure in the majority Black city.

Lationna dreamed of moving “somewhere that’s nice and quiet and peaceful.” Her ultimate hope was to leave for Dallas, where she thought she could give Royalty better opportunities. But she would have been happy to move to Clinton, a town just five minutes down the road, made up of tidy subdivisions with squat houses that all have driveways and yards. A sign at the edge of town seemed addressed to her: “You belong here.”

But moving even five minutes away costs money they didn’t have.

“I just wanted everything to be better than what it is now,” Lationna says. Kendall felt the same. “We were not ready to have a baby.”

Shortly after Lationna took the test, she tried to make an online appointment to get an abortion at Jackson Women’s Health — commonly known as the Pink House, nicknamed for its Pepto Bismol-colored outer walls. Since 2004, it was the only abortion clinic in Mississippi. She never heard back.

Just a month prior, the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade with its decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, a case that originated in Lationna’s home state when the Pink House sued Mississippi over its 15-week abortion ban. Mississippi’s preexisting abortion ban trigger law went into effect automatically on July 7; the Pink House ceased operations the same day.

The evening after she tried to contact the Pink House, while watching the news at her mother’s house, Lationna saw a TV segment about Mississippi’s abortion ban. That’s when she realized, “Oh, that’s why they’re closed. They passed a law already, so I can’t do anything.”

Lationna was, she says, “stuck.”

Lationna and Kendall looked into traveling to another state, but they didn’t have the money. The best option they could find was a clinic in Philadelphia, where the procedure alone would cost around $700, not including the hundreds it would take to get there and back. In the confusing aftermath of the verdict and the new bans, Lationna also feared if she left the state to get an abortion, she’d be arrested upon her return. (Mississippi’s ban charges anyone who performs an abortion in the state with a felony, although officials have said they won’t prosecute people who seek abortions themselves.)

Instead, Lationna had her baby at the end of January. That makes her one of the first people to give birth after being unable to end a pregnancy because of the new abortion bans that have been passed or gone into effect in 14 states since the Dobbs decision. (Five other states have banned the procedure after early gestational limits.) After a half-century of recognizing a constitutional right to abortion — even if access was spotty to nonexistent in many places — the United States has entered a new era.

Lationna found herself at a particularly cruel nexus: about to undertake having a child she hadn’t planned for in a state that ranks at the bottom of the nation in terms of the support it offers pregnant people and new parents. Even with a job, a partner and a family support system, Mississippi’s abortion ban put Lationna at extreme risk of poverty. She would face the added costs of caring for another child with no extra resources to do so. And she would more than likely be forced to put her life goals on indefinite hold.

Lationna’s story is a glimpse of things to come, on a massive scale, in our new, post-Dobbs America, foreshadowing the economic harm as yet untold numbers of people will endure and the dreams a new generation will be forced to put aside.

Driven into desperation

Even before Mississippi’s trigger law went into effect in July 2022, Mississippians were no stranger to the need to travel out of state to get an abortion because of the state’s lack of clinics. Mississippi also instituted a mandatory waiting period for people in need of an abortion, which led many to miss work and need additional childcare to make appointments. Women who lived in poorer areas, according to a study by Kari White, associate professor of social work at the University of Texas, Austin, were especially likely to face barriers to access and end up getting abortions later in their pregnancies.

As always, “those who have” can access abortion more easily than “those who don’t,” says Diana Derzis, who owned the Pink House. “But at least women had an option.” Most of the clinic’s patients were women of color who were struggling financially and already had children, Derzis says. Many were there because they couldn’t afford to have another child.

That steady drumbeat of need kept up right until the Pink House closed in the summer of 2022. The clinic stayed open seven days a week in an attempt to serve as many people as it could. “We were seeing 40 and 50 patients a day,” Derzis says. “The phone was off the hook.”

The Dobbs decision has enabled not just Mississippi but all of the surrounding states to ban abortion. “Given both the high levels of economic need and inequities that we have already seen in Mississippi,” White says, “it really does seem that very few people will be able to travel someplace else to get abortion care.” After Dobbs, only about half the people nationwide who were blocked from accessing an abortion in their home states have traveled elsewhere.

For a preview of what that will mean in the wide swaths of the country that now have little to no abortion access, we can look at the landmark turn-away study by Diana Greene Foster, a demographer at the University of California, San Francisco. In 2008, she started following women who sought abortions in states that banned the procedure at certain gestational limits, comparing what life looked like for those who were able to obtain an abortion with those who were refused.

“The two groups started out the same,” Greene Foster notes. But over time, those who were turned away fared far worse. Six months later, they were nearly four times as likely to be living in poverty and more than three times as likely to not be working. Those who did work were less likely to be doing so full time. They were also more likely to drop out of school and less likely to graduate, and those who had aspirational life plans were far less likely to achieve them. Even five years later, the women who couldn’t obtain abortions were 78% more likely to be in debt and 81% more likely to be bankrupt, evicted, or have a tax lien against them.

It’s not just the women who suffer. Their previous children — 60% were already mothers — were more likely to live in poverty and struggle with developmental milestones. Most women who had wanted another child later in life, under different circumstances, didn’t go on to have another, because “when they have a child before they’re ready,” Greene Foster says, those better circumstances don’t arrive.

“Every area in which there was a difference, women who were denied an abortion fared worse than women who received it,” Greene Foster says — and they knew it. Greene Foster had initially asked her subjects why they wanted an abortion; years later, she found out: “Everything they were concerned about came true for the people who were denied.”

Other research has found that women living in states with what are known as TRAP laws — short for targeted restrictions on abortion providers, which make it harder for clinics to operate — were less likely to be able to switch jobs or find higher-paying work, perhaps because women forced to have children they aren’t ready for have fewer resources to tide them over while they look for better positions or go back to school.

TRAP laws have indirect impacts too, says Kate Bahn, who researched them as an economist at the Washington Center for Equitable Growth. Women unsure of whether they’ll be able to control when they have children might opt out of majors and careers that take a lot of time and work. The policy landscape “shapes how one plans for the future.”

Even if these states offered generous safety nets, however, they would never make up for the loss of autonomy people face when they can’t end unwanted pregnancies. “That’s the fundamental piece,” Bahn says. “Women need to be able to make choices for themselves to have economic opportunity and contribute to economic growth.”

Ready or not

Lationna never graduated from college. She was 21 when she got pregnant with Royalty, and then finishing school proved too much. Since then, she realized her real passion was in hair and makeup, helping others feel confident and powerful. “When you step out, you want to feel yourself, feel comfortable, can’t nobody touch you,” she says. “That’s how I want to make everybody feel.”

Even after Lationna started the school IT job, she did hair and makeup on the side, seeing clients at home to make extra money, charging $50 for makeup and $70 for hair — far less than what she could charge if she were licensed. In 2022, Lationna started making plans to get that license, calling around to cosmetology schools and looking into a program at her work that helps pay for education. She wanted to do “something I actually want to do and don’t mind getting up and doing it every day,” she says. She began dreaming of working for herself, even owning a salon.

But amid those plans, in spring 2022, she got pregnant. It happened during a remarkably short window: her hormonal birth control implant had expired, so she had it removed. That cost $300, even with health insurance, and she didn’t have enough money saved to get it replaced right away. Lationna was pregnant just a month later.

“I didn’t think I was going to get pregnant that fast,” she says.

Lationna has mixed feelings about abortion, but she is adamant that “it’s not my decision to make with anybody [else’s] body.” She wished Mississippi’s lawmakers felt the same. “I just hate that they [can] vote on it,” she says.

The states that have banned abortion are the same ones that do the least to help pregnant people and new parents make ends meet. Eight of the 14 states that now ban abortion also fail to ensure pregnant workers have the right to workplace accommodations. None have guaranteed paid maternity and paternity leave or paid sick days, and five have refused to extend postpartum Medicaid coverage for mothers in the first year after giving birth — an extremely critical period for parents. Adding to parents’ struggles to provide and care for their new kids, 10 states haven’t raised their minimum wages higher than the federal rate of $7.25 an hour, six have refused to expand Medicaid to most low-income adults, and none give workers the right to humane scheduling practices.

“These policies cluster together in such harmful ways,” says Shaina Goodman, director for reproductive health and rights at the National Partnership for Women & Families.

Mississippi ranks dead last on all of these measures: It banned abortion while failing to guarantee paid family leave, paid sick days, pregnancy protections at work, scheduling rights and a higher minimum wage. It hasn’t expanded Medicaid, and only this March did it pass legislation extending postpartum Medicaid coverage for up to 12 months.

Mississippi banned abortion while failing to guarantee paid family leave, paid sick days, pregnancy protections at work, scheduling rights and a higher minimum wage.

The outcomes for residents are grim. Mississippi has the highest overall and child poverty rates in the country, with more than a quarter of its children living in poverty. Its infant mortality rate also tops the list, and its maternal mortality rate is among the highest. Both outcomes are worse yet for Black Mississippians. Black babies in the state are twice as likely to die as white babies, and pregnant Black women are three times as likely to die as pregnant white women. The state also has the highest rates of preterm birth and low birthweights in the country.

“We want to tell people to have babies here,” says Sandra C. Melvin, chief executive officer of the Institute for the Advancement of Minority Health, “but when the babies get here, we don’t do the things we need to do to ensure they’re safe and healthy.”

With abortion banned, Mississippi is expecting at least 5,000 more babies to be born in the state each year.

“We just got to make it work”

Lationna’s first pregnancy, with Royalty, had gone smoothly. This time was harder. She had a lot of pelvic and back pain, which made it difficult to stay active. By December, she could no longer touch her feet and had trouble walking. It was hard to get out of bed in the morning and, even with a grace period to accommodate her pregnancy at the elementary school where she worked, she still had a hard time arriving before 8 a.m.

Lationna’s job didn’t offer any paid maternity leave — only paid sick days, and she had used all five of those, plus all of her six personal days, on prenatal appointments, along with the time Royalty was home sick with the flu for the entire week before Thanksgiving.

All she had was the federally mandated option of 12 weeks of unpaid leave. To avoid going entirely without income, Lationna planned to find a remote job she could do from home while watching the baby. Ideally, she could keep doing that rather than return to her school job. “I got to make ends meet, help his dad with the bills,” she said, and she sent out applications “left and right.”

Lationna got a bit of government help — $470 a month in food stamps and a voucher to cover Royalty’s $55-a-week after-school care — but Mississippi’s safety net is threadbare and hard to access. She never bothered to apply for cash benefits from the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program. Applications are overwhelmingly rejected — just 4% of eligible Mississippians receive it, and even then, the maximum is $260 a month for a family of three.

Her employer-provided health insurance wasn’t great, with copays higher than $100 per doctor’s appointment, so she tried not to make appointments. When she got pregnant, she was able to enroll in Medicaid, which covered all of her prenatal care without a copay.

At one point, Lationna had looked into trying to get a Section 8 rental voucher; she gave up when she realized how long the waitlist was — in Mississippi, an average of 8 to 10 years. She once managed to secure an apartment in a low-income complex in North Jackson, when Royalty was a toddler, but it had such severe black mold that his clothes, shoes and bedding were constantly covered with growths. The landlord refused to treat it, so Lationna was forced to move to their current market-rate apartment.

In December 2022, Lationna was still trying to get clothes, a car seat and a stroller for the coming baby. They didn’t have the money. “It is stressful,” she said at the time. “I am so terrified.”

But Lationna and Kendall found ways to mentally adjust to the idea of having a baby together. After they realized they couldn’t afford an out-of-state abortion, they had a long talk, and Lationna “had a coming to terms” in realizing “this baby’s still going to grow.” She prayed and she talked to her mother, who told her she had to face her responsibilities. She tried to see it as “just another blessing.”

“We just got to make things work,” she resolved.

On Christmas morning, as Royalty opened the presents laid out under their tree, Kendall handed Lationna a box with a ring inside, then got down on one knee. “I started crying,” Lationna said. “I didn’t think he wanted to.” But she also had hesitations: She’d wanted to get married after her family was financially stable, once they were living in a house. She said yes while planning to put the actual ceremony off until she could find a new, better paid job.

She was very clear that she didn’t ever want to get pregnant again. “I really want to have my tubes tied after this,” she said. “I’m done.”

Bringing baby home

On morning of January 30, Lationna’s baby was born: Kingsley, a 7-pound boy with a serious face and soft curls covering his head. In the end, the delivery went well, except for the fact that the hospital had no hot water — something that may or may not have been related to the ongoing water problems in Jackson and which meant she had to take an icy shower after the birth.

Lationna wasn’t able to get her tubes tied after delivery as she had wanted. Her doctor didn’t give her the paperwork ahead of the delivery, and then, at the hospital, she was talked out of it, she says, because she was told it wouldn’t be 100% effective. Instead, she was given the hormonal birth control implant she had before — the same one she’d been unable to replace just before she got pregnant.

Two days after Kingsley was born, Lationna brought him home. Despite being on the first floor, their apartment was dark like a basement unit because of the shades covering their single living room window. Still, Lationna didn’t sleep. Kingsley, like many newborns, slept all day and was awake all night. When we met in early March, there were dark circles under Lationna’s eyes.

Kendall was back to work as soon as Lationna and the baby left the hospital, working from 7:30 in the morning until 6:30 at night, plus his side hustle detailing cars on the weekends. He came home exhausted. Since Kendall had become the breadwinner, covering all of their bills while Lationna was on unpaid leave, Lationna felt obligated to take care of everything at home. “I’m going to let you have your sleep,” she told Kendall, and stayed up with the baby by herself all night.

After a day or two, Lationna started to feel depressed, something she never experienced after Royalty was born. She would “just cry, cry, cry for no reason,” she says. She mentioned it at her four-week doctor appointment, but she was told it was normal, so she tried to cope on her own.

The only time Lationna was able to really rest was in the morning, when she let Kingsley sleep on her and she drifted off; if she tried to put him down, he immediately started crying. Most of the day he slept silently on her body, nestled on her shoulder or curled against her forearm, tattooed with “Royalty” in big red lettering. She planned to get another tattoo with Kingsley’s name, eventually. Every time she helped Kingsley shift to a new sleeping position, she showered his plump cheeks with kisses.

Lationna’s mother came by in the evenings after work, but even with that help, Lationna chafed at her situation. Kendall argued he had it harder, working outside for long hours, but Lationna felt her situation — being stuck at home all day caring for a newborn by herself — was worse. “I wish I was a dad [rather] than a mom,” she said, “because they get to get up and leave the house whenever they want to instead of being here with the kids.” Lationna longed for that freedom — freedom she’d had when she only had Royalty. “I feel like I’m in a prison,” she said.

She also felt stuck in an unfamiliar and uncomfortable body. She longed to be able to exercise and “lose this mom weight,” she said. She feared falling back into depression if she couldn’t move her body. She worried that her face and neck skin had been darkened by pregnancy and wanted to buy new makeup to better cover it up. “When I look in the mirror, I don’t recognize myself anymore,” she said. “I just want to get my old body back. I want to get my old self back.”

Lationna told herself she had to suck it up. “I can’t complain, because I’m not providing. I can only sit here and just cope with it until I’m able to get back on my feet and get back to where I need to be at.” But she couldn’t get comfortable with the situation. “I really don’t like depending on anybody,” she says. “I’d rather have my own.

Barely, barely, barely

After Mississippi banned abortion, conservative lawmakers, including Republican Gov. Tate Reeves, vowed to offer more support for parents and babies. A study group was formed in the state Senate to consider legislation.

But most of the proposed bills this session, from tax credits for parents to more fiscal support for crisis pregnancy centers, failed. Out of 60, more than half had been rejected by early February. None advanced that would have helped parents access and afford childcare. Bills to ensure paid family leave and rights for pregnant workers, plus seven to increase the minimum wage, died without consideration.

Instead of finding more resources to help poor parents, Republican leaders want to use the state’s projected $3.9 billion budget surplus to entirely eliminate its income tax. That would erase a third of Mississippi’s revenue.

The one item the legislature accomplished this session on its post-Dobbs agenda was extending postpartum Medicaid coverage for 12 months. Previously, postpartum parents were kicked off after 60 days. The law goes into effect July 1.

It’s unclear if the law will allow parents like Lationna, whose 60 days ended March 31, to maintain Medicaid coverage. The state Medicaid department did not respond to In These Times’ request for information on whether people like her will be removed from the program before July.

Lationna never got a new job despite continuing her flurry of applications while home with Kingsley. Equipment she’d bought to work a remote position, including a monitor and headset, sat in the living room, left over from when she thought she had secured one that paid $15 an hour, only to realize she couldn’t swing the four-week unpaid training.

She was supposed to return to her school IT job March 24, before Kingsley would even be old enough to get the shots he needed to go to daycare. When she called the daycare she wanted in early March, it didn’t have any openings, and Lationna was told to call back the week before she returned to work.

Then there was the cost: $90 a week. Originally she had wanted to get a voucher, but Mississippi doesn’t make that easy. Before an unmarried mother can get a voucher, she has to cooperate with the Child Support division, which typically determines the paternity of the child and then orders child support payments from the father — no matter how involved he is with his children. The state then takes most of the money to pay itself back for benefits. If a mother doesn’t comply with that process for any reason, her application is automatically rejected. “It’s almost always a barrier,” said Carol Burnett, executive director of the Mississippi Low-Income Child Care Initiative. Mississippi has also consistently left millions of dollars in federal funding for childcare unspent, such that only 10% of eligible children were served before the pandemic.

Lationna’s is one of thousands of dreams that have been and will be deferred as people across the country are blocked from getting the abortions they need and are forced to give birth to and raise children they weren’t ready for.

Lationna and Kendall decided not to go through the onerous child support process. “He hates the words ‘child support’ because he’s going to be there for his kids,” she says. “We just decided he wanted to pay out of pocket.” (They eventually decided to pay Lationna’s 80-year-old great aunt $50 a week to watch him for the time being.)

Kendall and Lationna were making ends meet — but just barely. Determined to stockpile enough money so the family could move somewhere new, Lationna had done some hair and makeup for clients — putting Kingsley in a swing, praying he wouldn’t wake up, and asking her clients to hold him if he did. She tried to put that money aside, and they planned to open a joint savings account, but as of March they hadn’t managed to save anything.

Securing the things Kingsley needed hadn’t been a huge financial burden yet. Lationna’s coworkers had bought her enough diapers and wipes to fill a closet and her family gave her clothes and gear at her baby shower. But by one month, Kingsley was already outgrowing his clothes, and Lationna knew she would have to go shopping soon. Friends and family tend to be generous when babies are first born, but that largesse typically disappears as babies get older. And the cost of caring for an extra child was only going to grow. While Lationna’s family hadn’t yet faced extreme consequences like homelessness or hunger, their budget was significantly constricted.

Lationna’s dream of going to cosmetology school was put on indefinite hold. “Me getting pregnant and just having two kids, it’s going to be too hard for me to do,” she said, staring down at Kingsley’s sleeping face as she sat on her couch in fuzzy pink slippers and a flowered hair bonnet. “That just threw everything out the window.”

Lationna’s is one of thousands of dreams that have been and will be deferred as people across the country are blocked from getting the abortions they need and are forced to give birth to and raise children they weren’t ready for. Before the Pink House was forced to close, says former owner Diana Derzis, “I was seeing women who were able to attain things they would not have been able to attain had they not had that option there.” But “when you take that away,” she continues, “you have removed an option for their futures to be brighter and better, and that of their children.”

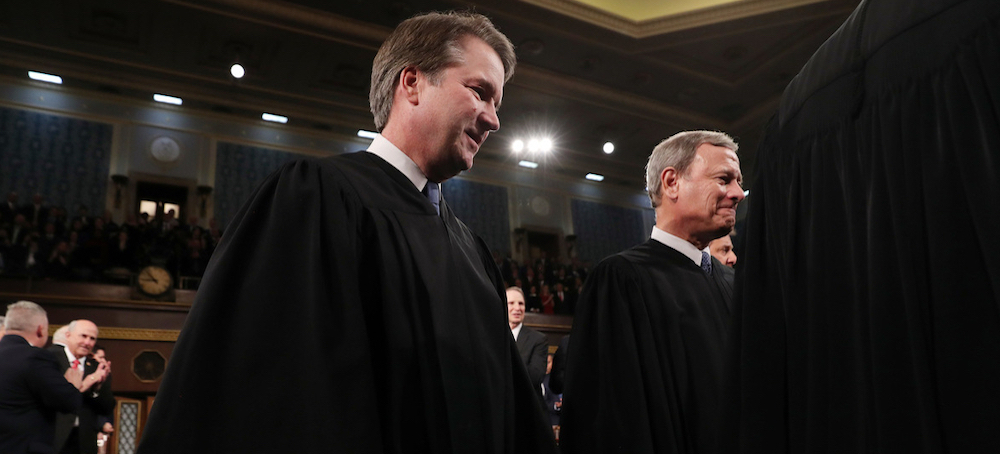

READ MORE  Justice Brett Kavanaugh and Chief Justice John Roberts. (photo: Getty Images)

Justice Brett Kavanaugh and Chief Justice John Roberts. (photo: Getty Images)

The Court’s decision in United States v. Texas stops rogue judges from seizing control of law enforcement.

The Court’s decision in United States v. Texas was 8–1, with all eight justices in the majority concluding that Tipton didn’t even have jurisdiction to hear this case in the first place — though they split 5-3 on why Tipton lacked jurisdiction. Only Justice Samuel Alito, the Court’s most reliable Republican partisan, dissented.

The case concerned 2021 guidelines, issued by Secretary of Homeland Security Alejandro Mayorkas, that instructed ICE agents to prioritize enforcement efforts against undocumented or otherwise removable immigrants who “pose a threat to national security, public safety, and border security and thus threaten America’s well-being.”

Two red states, Texas and Louisiana, sued, essentially arguing that ICE must arrest more immigrants who do not fit these criteria. Moreover, because Texas federal courts often allow plaintiffs to choose which judge will hear their case by deciding to file their lawsuits in specific parts of the state, these two red states chose Tipton — a staunchly anti-immigrant judge who has been a thorn in the Biden administration’s side since the first week of his presidency — to hear this lawsuit.

In one of the most predictable events in the US judiciary’s history, Tipton promptly obliged the two states by striking down Mayorkas’s guidelines.

Justice Brett Kavanaugh’s opinion in Texas holds that no federal judge should have ever even considered this case. As Kavanaugh explains, the plaintiff states “have not cited any precedent, history, or tradition of courts ordering the Executive Branch to change its arrest or prosecution policies so that the Executive Branch makes more arrests or initiates more prosecutions.” To the contrary, the Court held in Linda R. S. v. Richard D. (1973) that “a private citizen lacks a judicially cognizable interest in the prosecution or nonprosecution of another.”

That rule, Kavanaugh announces, controls the Texas case. Just as a private citizen may not sue to force the government to arrest or prosecute someone else, a state government also may not bring such a lawsuit.

Kavanaugh’s opinion also reaffirms a longstanding doctrine, known as “prosecutorial discretion,” which permits law enforcement officials to determine who to arrest, and who to otherwise enforce the law against, without interference from the judiciary.

The decision is a serious blow to Republican efforts to control federal immigration policy by seeking injunctions from sympathetic judges. From the earliest days of the Biden administration, Republican Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton has taken advantage of the unusual rules permitting him to often choose which judge hears his cases to secure court orders blocking President Biden’s immigration policies. (To be clear, there is no evidence that these rules were created for the purpose of allowing someone like Paxton to game the process used to assign cases to judges. But they certainly allow him to do so.) Just six days into Biden’s presidency, for example, Tipton granted Paxton’s request to block a 100-day pause on deportations that the new administration announced in its first week.

At the very least, the Court’s Texas decision should mean that judges like Tipton can no longer decide who is or is not arrested.

That said, the decision does contain some language that anti-immigrant judges may latch onto to impose their preference on the country — including a paragraph that reads like it was written to preserve lawsuits challenging the Obama-era Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program.

And there is one other very frustrating thing about this case. Although the Supreme Court eventually ruled that Tipton is not the head of ICE and cannot decide who its agents arrest, it rejected a request to temporarily block Tipton’s decision last July.

In other words, by sitting on this case, a Supreme Court dominated by conservative Republican appointees effectively let Tipton control ICE for more than a year.

Why prosecutorial discretion exists

Texas’s lawsuit was rooted in a federal statute which states that the United States “shall take into custody any alien” who commits certain immigration offenses. In effect, they argued that the word “shall” is a mandatory command that forces ICE to make mass arrests.

But this argument runs afoul of 150 years of well-settled law. As far back as Railroad Company v. Hecht (1877), the Supreme Court held that “as against the government, the word ‘shall,’ when used in statutes, is to be construed as ‘may,’ unless a contrary intention is manifest.”

One reason for this strong presumption that federal laws do not impose arrest or prosecution mandates on law enforcement is that it is often literally impossible for a law enforcement agency to arrest every single person who violates a law — imagine the massive police state that would be required, for example, to pull over every single driver who violates a traffic law.

As the Justice Department explained in a 2014 memo, “there are approximately 11.3 million undocumented aliens in the country,” but Congress has only appropriated enough resources to “remove fewer than 400,000 such aliens each year.” That means that leaders of immigration agencies like ICE necessarily must set priorities, and make choices about which deportable immigrants will be targeted and which ones will effectively be tolerated within US borders.

Indeed, as Kavanaugh writes in his Texas opinion, this ability to set priorities and to decide when not to enforce the law has been a regular feature of federal immigration law across many administrations. “For the last 27 years since” the immigration statutes at issue in Texas “were enacted in their current form,” Kavanaugh writes, “all five Presidential administrations have determined that resource constraints necessitated prioritization in making immigration arrests.”

For this reason, the Court has long held that law enforcement agencies may exercise “prosecutorial discretion” without interference from the courts. As the Court held in Heckler v. Chaney (1985), “an agency’s decision not to take enforcement action should be presumed immune from judicial review.”

As Kavanaugh emphasizes, his opinion in Texas “simply maintains the longstanding jurisprudential status quo.” Tipton should have never heard this lawsuit in the first place, and there is more than a century of US law informing him why he should not have done so.

The Texas case is not a total victory for the Biden administration

All of this said, there are three aspects of this case that may embolden judges like Tipton to continue sabotaging Biden’s immigration policies.

The first is that the Supreme Court appears to have manipulated its calendar to leave Tipton’s order in place for as long as possible.

This is not a hard case, and Tipton’s errors should have been obvious to any judge with even a passing familiarity with the Court’s prosecutorial discretion decisions. And yet the justices sat on the case for nearly an entire year before finally ruling, in a decision joined by every justice except the hyper-partisan Alito, that Tipton did not have jurisdiction to hear this case.

They should have blocked Tipton’s decision last July, when the Biden administration first asked them to do so.

Additionally, while Kavanaugh’s opinion holds that judges ordinarily should not interfere with a law enforcement agency’s decision not to arrest a particular individual, he does write that the “calculus might change if the Executive Branch wholly abandoned its statutory responsibilities to make arrests or bring prosecutions.”

To be sure, Kavanaugh also suggests that this exception to the ordinary rule may only apply when the “Executive has entirely ceased enforcing the relevant statutes,” and there is no plausible argument that the Biden administration has stopped enforcing federal immigration law altogether. But judges like Tipton have shown an extraordinary willingness to interfere with federal immigration policy, even when the Supreme Court has clearly told them not to do so. So it’s not hard to see someone like Tipton latching onto Kavanaugh’s “wholly abandoned” language to seize control of immigration policy once again.

Finally, Kavanaugh’s opinion also says that “a challenge to an Executive Branch policy that involves both the Executive Branch’s arrest or prosecution priorities and the Executive Branch’s provision of legal benefits or legal status could lead to a different standing analysis.” That language reads like it was tailor-made to allow legal challenges to DACA, a program that allows hundreds of thousands of undocumented immigrants to live and work in the United States, to move forward.

The Supreme Court, in other words, slow-walked its decision that Alejandro Mayorkas, and not Drew Tipton, is the nation’s chief immigration enforcement officer. And it did not close every possible gate that a rogue judge like Tipton might try to walk through in order to sabotage President Biden’s policies.

But the Texas decision is still an important victory both for the administration and for immigrants. And it suggests that even this very conservative Supreme Court won’t let the judiciary’s right-most fringe act without adult supervision.

READ MORE  A Starbucks barista. (photo: USA Today)

A Starbucks barista. (photo: USA Today)

Starbucks Workers United, the group leading efforts to unionize Starbucks workers, tweeted Friday that more than 150 stores and 3,500 workers "will be on strike over the course of the next week" due to the company's "treatment of queer & trans workers."

Workers at Starbucks' flagship store, the Seattle Roastery, went on strike Friday, with dozens of picketing outside.

Earlier this month, the collective accused Starbucks of banning Pride month displays at some of its stores.

"In union stores, where Starbucks claims they are unable to make 'unilateral changes' without bargaining, the company took down Pride decorations and flags anyway — ignoring their own anti-union talking point," the group tweeted on June 13.

In a statement provided to CBS News Friday, a Starbucks spokesperson vehemently denied the allegations, saying that "Workers United continues to spread false information about our benefits, policies and negotiation efforts, a tactic used to seemingly divide our partners and deflect from their failure to respond to bargaining sessions for more than 200 stores."

In a letter sent last week to Workers United, May Jensen, Starbucks vice president of partner resources, expressed the company's "unwaveringly support" for "the LGBTQIA2+ community," adding that "there has been no change to any corporate policy on this matter and we continue to empower retail leaders to celebrate with their communities including for U.S. Pride month in June."

Since workers at a Starbucks store in Buffalo, New York, became the first to vote to unionize in late 2021, Starbucks has been accused of illegal attempts to thwart such efforts nationwide. To date, at least 330 Starbucks stores have voted to unionize, according to Workers United, but none have reached a collective bargaining agreement with the company.

Judges have ruled that Starbucks repeatedly broke labor laws, including by firing pro-union workers, interrogating them and threatening to rescind benefits if employees organized, according to the National Labor Relations Board.

In March, former Starbucks CEO Howard Schultz also denied the allegations when he was grilled about them during a public Senate hearing.

"These are allegations," Schultz said at the time. "These will be proven not true."

READ MORE  Brazil's former president Jair Bolsonaro. (photo: Al Drago/Bloomberg)

Brazil's former president Jair Bolsonaro. (photo: Al Drago/Bloomberg)

The former far-right leader will be tried by a panel of seven judges in the country's electoral court system, so while he won't face criminal penalties, he could see his political career cut short. The sentence for such crimes is a ban on running for office for eight years.

The trial will be shown in its entirety on YouTube.

An opposing party in last year's presidential election brought the accusation to the electoral court, regarding a speech Bolsonaro gave to foreign diplomats in July 2022. In a nearly 50-minute presentation, Bolsonaro rehashed many of his previous attacks on Brazil's electronic voting system. He claimed, without providing evidence, that its electronic machines are vulnerable to hackers and prone to fraud.

Some of the foreign diplomats in attendance told the New York Times that Bolsonaro, who was trailing in the polls at the time, appeared to be preparing to challenge his inevitable defeat and discredit the vote before it even took place. He ultimately lost by the slimmest margin since Brazil returned to democracy in the 1980s. And while Bolsonaro never conceded defeat in the election, he didn't block the transfer of power, instead opting to leave the country for the United States two days before current President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva's Jan. 1 inauguration.

Thursday's case is one of 16 that Bolsonaro is facing in Brazil's Superior Electoral Court. There are multiple civil and criminal cases, including one into his possible encouragement of attacks on the capital's government center by a mob of his supporters on Jan. 8.

"This is not the strongest case, but it is the first that is going to trial," says Malu Gaspar, a columnist with O Globo newspaper.

Prosecutors allege that Bolsonaro abused his power to try to influence voters with his criticisms of Brazil's elections. They say he used the government airwaves, the public broadcaster TV Brasil and social media to disseminate disinformation.

Lawyers for Bolsonaro have said the evidence is weak and that the diplomats the president was speaking to were all foreign citizens who can't even vote in Brazil.

NPR sought comment from one of Bolsonaro's lawyers, Tarcisio Vieira de Carvalho, but calls were not returned.

His supporters fear judicial overreach

Defense lawyer Karina Kufa, who has represented Bolsonaro in several other cases, but not this one, says the former president was just refuting claims by election officials that the machines worked flawlessly. "He did it to show other governments how the electronic ballot box actually works, because, according to him, only one version was shown," she told NPR. He was just giving his version, she says, which is not a crime.

She says the court is rushing this case and that a possible ban on Bolsonaro's future political eligibility is a dangerous overreach by the justices and "very worrying for our democracy." She also says the courts are removing other politicians, including mayors and governors, from office "for any reason."

President Lula has not commented directly on the case, but has openly criticized his political rival, accusing him of encouraging supporters to ransack the capital. But he said this week, before leaving on a state visit to Italy and France, that justice will be meted fairly.

"Everyone will have a chance to defend themselves. I want people to rest assured that we are going to investigate. They will be judged by the common justice and will go to jail if they have committed a crime. If not, people go back to living their lives in peace," he said.

Even if he's disqualified from office, he'll remain a strong political figure

If Bolsonaro were barred from running for office for eight years, that wouldn't mean he'd be out of politics completely, says Gaspar. "I think he is very strong; he is kind of a symbol on the right. And he is going to travel Brazil all year to attract mayors and governors and other politicians to his party," she says.

Bolsonaro is not required to be present at the proceedings and even has scheduled a rally in the conservative south of the country, to take place at the same time as the trial on Thursday.

But if barred from office, it will be very difficult for Bolsonaro to remain the leader of the right in Brazil, says Guilherme Casarões, a political scientist at the Getúlio Vargas Foundation in São Paulo.

"It's going to be even harder for him to sustain his position and to keep his supporting base together," he says.

And given Brazil's fractious and multiple political party system, Casarões says there are plenty of other politicians in the wings ready to fill the role of leader of the right.

A ruling may come quickly

The Superior Electoral Court has only three more sessions before it recesses for all of July. It could quickly rule in Bolsonaro's case since only a simple majority is needed to convict.

However, a single judge could ask for a review of the case, leading to a lengthy postponement. With 15 other cases before the court, including more accusations of coordinating misinformation campaigns and abuse of power, Bolsonaro's lawyers will be back before the justices soon enough.

READ MORE  Pollution from a factory. (photo: Science Focus)

Pollution from a factory. (photo: Science Focus)

New research finds children exposed to “safe” levels of three EPA-monitored air pollutants show altered developmental processes in neural networks crucial to some social and cognitive functions.

But a new study suggests those standards may be too high, and as a result, children across the U.S. exposed to “safe” levels of pollution may be experiencing adverse effects to their brain development.

The study, published earlier this week in Environment International, hinges on an analysis of two sets of MRIs of children’s brains from one of the largest long-term studies of brain health and child development in the country.

Researchers from the Keck School of Medicine at USC worked with 9,497 participants in the study, establishing a baseline MRI when they were between ages nine and 10; two years later, the researchers conducted another MRI, looking for changes in brain function over time. Once they had each participant’s baseline and second MRI, the researchers ran environmental data from Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) air monitors through a model to help establish the air quality within a half mile radius of each child’s home.

What they found came as a mild surprise: children exposed to legally acceptable levels of fine particulate matter pollution (PM2.5), nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and ground-level ozone (O3) across the U.S. showed signs of altered brain connectivity in areas crucial to adolescent development.

Adolescence is “this period of vulnerability,” said Megan Herting, an associate professor of public health sciences at USC and the study’s senior author, that has “kind of been overlooked as an important time period in which air pollution might modify how the brain is growing and changing.”

To test that hypothesis, the research team established the local environmental pollution levels of particulate pollution, like soot, along with nitrogen dioxide and ozone for each participant, accounting for the season, proximity to roads and wind patterns. The researchers controlled for a participant’s sex, race, parental education level, household income and location.

Once they had each MRI and the environmental data, the team ran analyses to determine how neural networks in each participant’s brain were affected by the levels of pollution from PM2.5, NO2 and O3 in their surroundings.

They were specifically interested in brain functions that together “give rise to all sorts of cognitive and emotional functions that we use everyday,” said Devyn Cotter, a Ph.D. candidate in the department of public health sciences at USC, and the lead author on this study. The “salience network” governs how the brain switches its attention between tasks; the “friendship parietal network” affects executive functions like memory and processing speed, and the default mode network governs how people daydream.

If any of these networks were to deviate from their usual development, by forming too many or too few connections, “that could put you at higher risk down the line for emerging psycho pathologies,” said Cotter, potentially jeopardizing an adolescent’s future mental health.

“A lot of previous studies have looked at higher levels of air pollution,” said Herting, but the pollution levels in each participant’s environment “fell well below what EPA is setting as a safe threshold.” In the case of NO2, which is typically found in the emissions from cars, trucks and power plants burning fossil fuels, the average number of pollutants participants were exposed to was nearly 65 percent less concentrated than the standard set by the EPA.

The agency has not updated its NO2 annual average standard since it was first created in 1971.

These findings show “the long shadow that air pollution leaves on our health early in our lives,” said Robbie Parks, an assistant professor of environmental health sciences at Columbia University, who was not involved in the study. He called the analysis “robust,” and noted the study was one of the first to attempt to measure the direct mechanism by which pollution affects the brain.

The findings add momentum to the idea that “air pollution concentrations should be pushed even lower,” Parks said.

Marianthi-Anna Kioumourtzoglou, an assistant professor and colleague of Parks’ at Columbia’s School of Environmental Health Sciences, agrees. “We need stricter standards,” said Kioumourtzoglou, who was also not involved in the study. “We need to protect children’s brains because that’s their future.”

Kioumourtzoglou isn’t so sure this study will prompt the EPA to lower its “safe” pollution standards, a term she’s weary of because for many developmental outcomes “there is no safe level of pollution.” She said that creating these standards is inherently complicated for the agency, and that “unfortunately,” sometimes “people’s health is not necessarily their first priority.”

For Herting and Cotton, their work raises even more avenues for scientific inquiry, such as identifying any potential metals or chemicals in the particulate matter affecting adolescent brain development and then asking “to what degree those are having the neurotoxic effects long term,” said Herting.

Still, Herting said, one thing is clear: “We need cleaner air even beyond what we thought was working before.”

In 2021, the World Health Organization lowered its standard for acceptable levels of PM2.5—bits of pollution smaller than 2.5 microns, or about one-thirtieth the diameter of a human hair—to 5 micrograms per cubic meter of air. The EPA’s current standard is 12 micrograms per cubic meter of air; earlier this year, the agency proposed lowering that number to between 9 and 10, “reflecting the latest health data and scientific evidence.”

It is unclear how the EPA will interpret the results from this latest study, for which it provided a portion of the funding.

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.