Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

Former Sen. Al Franken (D-Minn.) is calling the Supreme Court “illegitimate” and Chief Justice John Roberts a “villain,” citing a number of controversies surrounding the nation’s highest court.

Franked resigned from the Senate in 2017 amid sexual harassment allegations.

He referenced the controversial confirmation of Justice Amy Coney Barrett, a Trump nominee, and the court’s decision last summer to overturn Roe v. Wade.

“The way they didn’t take up [Obama nominee Merrick] Garland and on saying, ‘It’s an election year,’ and then they, of course, put in Coney Barrett like eight days before the election. Then, of course, Dobbs and abortion.”

Balz said the court has “lost credibility” and has become “seen increasingly as one more partisan institution,” though he noted Roberts has tried to counter that perception.

“I think the Chief Justice is actually much more culpable for this division than people think,” Franken said, referencing some of Roberts’s decisions. “I think Roberts is much more the villain in this than people give him credit for.”

Polling has indicated a decline in Americans’ trust that the Supreme Court, with its nine lifetime-appointment Justices, is nonpartisan.

Franken’s comments also come amid new scrutiny over the Supreme Court’s ethics standards after reporting from ProPublica found Justice Clarence Thomas failed to disclose a series of luxury trips he’d taken, paid for by Republican donor Harlan Crow, and revelations that the same Texas billionaire had paid for the home Thomas’s mother was living in.

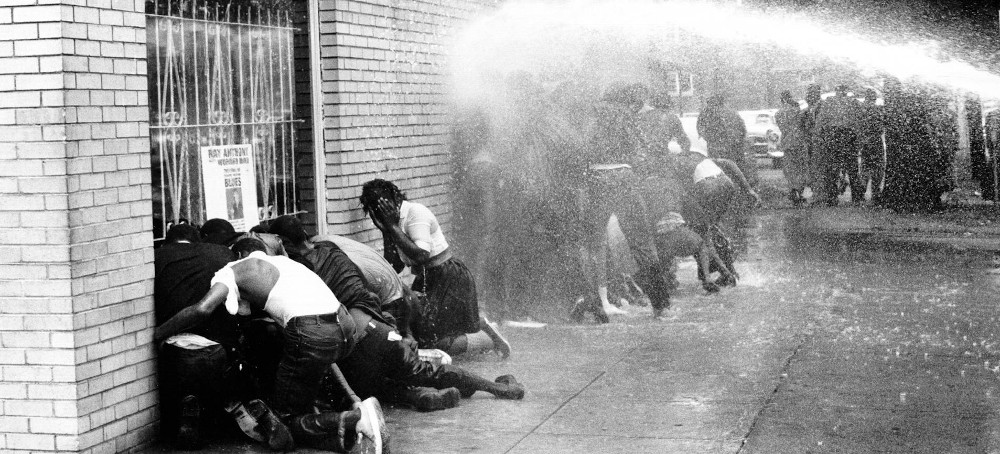

READ MORE  Civil rights protestors are attacked with a water cannon. (photo: Frank Rockstroh/Michael Ochs Archives)

Civil rights protestors are attacked with a water cannon. (photo: Frank Rockstroh/Michael Ochs Archives)

Sixty years ago today is known as “D-Day” in Birmingham, Alabama, when thousands of children began a 10-week-long series of protests against segregation that became known as the Children’s Crusade. Hundreds were arrested. The next day, “Double D-Day,” the local head of the police, Bull Connor, ordered his white police force to begin using high-pressure fire hoses and dogs to attack the children. One photograph captured the moment when a white police officer allowed a large German shepherd dog to attack a young Black boy. Four months after the protests began, the Ku Klux Klan bombed a Black Birmingham church, killing four young girls — Addie Mae Collins, Carole Robertson, Cynthia Wesley and Denise McNair. We revisit the history of the Children’s Crusade with two guests: civil rights activist Janice Kelsey, who joined the Children’s Crusade as a 16-year-old in 1963, and author Paul Kix.

In a moment, we’ll be joined by two guests to talk about the Children’s Crusade in Birmingham, but first let’s turn to the scholar and activist Angela Davis, who grew up in Birmingham. This is Angela speaking in 2013.

ANGELA DAVIS: And how many of us remember that it was young children — 11, 12, 13, 14 years old, some as young as 9 or 10 — who faced police dogs and faced high-power water hoses and went to jail for our sake? And so, there is deep symbolism in the fact that these four young girls’ lives were consumed by that bombing. It was children who were urging us to imagine a future that would be a future of equality and justice.

AMY GOODMAN: That was Angela Davis in 2013.

We’re joined now by two guests. Paul Kix, writer and author of the new book, You Have to Be Prepared to Die Before You Can Begin to Live: Ten Weeks in Birmingham That Changed America, he’s joining us from his home in Connecticut. And in Birmingham, longtime civil rights activist Janice Kelsey is with us. She joined the Children’s Crusade as a 16-year-old in 1963. She wrote about her experience in her own book, I Woke Up with My Mind on Freedom.

We welcome you both to Democracy Now! Janice Kelsey, let’s begin with you. It was 60 years ago today. I’m sure for you it doesn’t seem that long ago. Talk about what happened.

JANICE KELSEY: I remember, 60 years ago today, I woke up with my mind on freedom. I had attended student nonviolent workshops, and I was prepared, because I finally understood that it was more than just segregation, it was inequality. And Reverend James Bevel empowered us as youth to do something about it. And I was willing to do that.

AMY GOODMAN: And talk about what you did. Talk about what it meant to take to the streets, and the police violence in response.

JANICE KELSEY: Well, in the preparation sessions that were held at 16th Street Baptist Church, we had seen film of demonstrations in other places, so I saw people being hit, being called names and being mistreated for demonstrating. We were told that if you participate, some of this may happen to you, but this is a nonviolent movement, and you cannot respond, except to pray or sing a freedom song. So I went into it knowing that there may be some level of danger, but I was so incensed at having been mistreated all these years, until I was willing to sacrifice whatever was necessary to take steps to change the environment.

AMY GOODMAN: Just over four months later, the beginning of that Children’s Crusade, the 16th Street Baptist Church, was bombed. Four little girls, four young people, young women, were killed. One of them was Cynthia Wesley. You share the last name of Cynthia Wesley, Janice — Cynthia. Explain what happened.

JANICE KELSEY: Well, on that Sunday morning, I was at the church where I attended. And we had a speaker up. Our pastor interrupted the speaker and announced that 16th Street Baptist Church had been bombed and that there were some casualties. And that meant someone died. He said a prayer, and he dismissed church. Well, when we got home, people were calling our home. I have a large family. There were nine siblings. And my mom would not allow anyone else to answer the phone. And I kept on hearing her say, “No, not our family.”

Finally, when the news came on, the national news, they identified the casualties. Cynthia Wesley was one. I met Cynthia in elementary school when she was adopted by Claude and Gertrude Wesley, who were educators and friends of our family but not related. I was invited to come to their home for lawn parties. We went on field trips together. And Cynthia had just come to my high school. She was a ninth grader. I was an 11th grader. And I had not known anyone in my age group to die, let alone to be killed at church. I was devastated to hear Cynthia had died.

But there was a connection with the other girls, as well. Carole Robertson’s father, Alvin Robertson, was my band teacher in elementary school. And his wife taught at the same school where my sister taught, and they were friends. Denise McNair was 11, and her father, Chris McNair, was our milkman. He used to deliver milk and juice to the home. Addie Collins, I did not know her family, but she had a sister in the same class with one of my brothers.

And I was just devastated, because I thought people were proud of the courage that we had displayed in the spring of the year. I didn’t know it made someone so angry that they would react in such a violent way.

AMY GOODMAN: So, let’s bring Paul Kix into this conversation, who has just published the book today, You Have to Be Prepared to Die Before You Can Begin to Live: Ten Weeks in Birmingham That Changed America. Paul, if you can talk about why you wrote this book? Talk about your interracial family, George Floyd, and how that connects to what began 60 years ago today.

PAUL KIX: I’ll take the last part first. I mean, there was — from emancipation in 1863 to 1963, there were no — there was no equality, no sense of anything. That spring changed everything. And to have somebody like Janice — to be able to share this segment with someone like Janice is just — it gives me goosebumps, because just behind me you see my twin boys. I married my wife Sonya in a Jim Crow state of Texas. We live today on a shaded street where nobody harasses us for who we are. That’s because of what Janice just talked about. It’s the ability to not only, you know, put your life on the line in the moment, but to think about the lives ahead, the people in the future that might benefit from your actions in Birmingham.

So, my wife Sonya grew up in inner-city Houston, one neighborhood away from where George Floyd grew up. She had — her cousins went to the same high school, Yates High, as George. Sonya was the same age as George when George was murdered, 46.

And so, that’s a long way to say that we did not shield our kids from that sort of coverage. It was the first time they had ever seen something like that happen, where an innocent Black man was killed by police officers. And our twin boys, who are, again, behind me there in that photo, they were then 9. They had a lot of questions about what that meant for America. There was a — 2020, the latter half of 2020, was an incredibly difficult time. The boys would often run from the room in tears because of what they saw of George Floyd, because of what they saw — Jacob Blake was somebody else who was shot, by Kenosha, Wisconsin, cops. You know, one of my twin boys ran from the room, saying, “Why do they keep trying to kill us?” It was a hard time, 2020.

And I settled on a book project that very quickly became a family project, which was a way to try to inspire our three kids about how they might have courage in their own lives. And that extends back to what I see as the most pivotal period in the whole of the 20th century, and that is the spring of 1963 in Birmingham, Alabama, and in particular what happened on May 2nd and on May 3rd and on May 4th — excuse me — D-Day, Double D-Day, and through that weekend — the Children’s Crusade.

AMY GOODMAN: Let me turn to Vincent Harding for a moment. In 2008, I interviewed Vincent Harding, the pioneering historian, theologian and civil rights activist. In 1963, Martin Luther King invited him to come to Birmingham, Alabama, to help with the campaign.

VINCENT HARDING: King came especially to our attention there in Birmingham because there was a whole development in which many of the protesters were young people, and in some cases children, who came to play a crucial role in leading the struggle against segregation, partly because many of the adults were afraid to, couldn’t afford to, were worried about what would happen to them and their livelihoods if they did it. And the children took the role. They were arrested, after the dogs and the fire hoses. They were put in jail. They were not able, after a while — SCLC wasn’t able to get all of the bond money that was needed to get everyone out. And King, I remember very much, one Friday afternoon, in his motel room, simply said, “I don’t know what I can do to get the money to get these folks out, young and old, but I do know that what I can do is to go in there with them.” And so, he then led a march that was against the law at the time, and he was arrested and put into jail. It was in that context that he took the opportunity to work on that now-famous “Letter from Birmingham Jail.”

AMY GOODMAN: That was the late Vincent Harding in 2008, the great historian, scholar and pastor. He helped write King’s famous antiwar speech, “Beyond Vietnam: A Time to Break the Silence.” Well, this is Dr. Martin Luther King reading part of his “Letter from the Birmingham Jail,” from the documentary King: A Filmed Record.

REV. MARTIN LUTHER KING JR.: You deplore the demonstrations taking place in Birmingham. But your statement, I am sorry to say, fails to express a similar concern for the conditions that brought about the demonstrations. … Birmingham is probably the most thoroughly segregated city in the United States. Its ugly record of brutality is widely known. … There have been more unsolved bombings of Negro homes and churches in Birmingham than in any other city in the nation. These are the hard, brutal facts of the case. …

You may well ask: “Why direct action? Why sit ins, marches and so forth? Isn’t negotiation a better path?” … Nonviolent direct action seeks to create such a crisis and foster such a tension that a community which has constantly refused to negotiate is forced to confront the issue. …

You speak of our activity in Birmingham as extreme. … Was not Jesus an extremist for love: “Love your enemies, bless them that curse you, do good to them that hate you, and pray for them which despitefully use you, and persecute you.” … Will we be extremists for the preservation of injustice or for the extension of justice? …

I have no despair about the future. I have no fear about the outcome of our struggle in Birmingham, even if our motives are at present misunderstood. We will reach the goal of freedom in Birmingham and all over the nation, because the goal of America is freedom. … We will win our freedom because the sacred heritage of our nation and the eternal will of the Almighty God are embodied in our echoing demands.

AMY GOODMAN: From the documentary King: A Filmed Record, Dr. Martin Luther King reading his “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” which he had written just weeks before the Children’s Crusade. Paul Kix, you talked about D-Day and Double D-Day, the horrific picture that begins your book, this famous image from — it was May 3rd, 1963, of the 14-year-old African American boy, this German shepherd biting his stomach. And he is — he has such poise. He doesn’t seem to be responding, but with dignity. Talk about D-Day and Double D-Day.

PAUL KIX: It altered everything. Janice was saying just a moment ago about Reverend James Bevel. To go into D-Day and Double D-Day was effectively because there was no other choice. Birmingham adults were not going to protest. They would very likely lose their jobs. That’s what James Bevel realized. So, what the children did, we’ve seen those images. We’ve seen people like Janice being attacked with fire hoses. But I just want to frame for the audience what that actually meant.

Those fire hoses were mounted on metal tripods that, frankly, looked like it was meant for artillery. It could knock mortar loose from brick. It could strip bark from a tree at a distance of more than a hundred feet. A lot of times kids were hit at less than 50 feet. Some of the raw footage from that day shows — from Double D-Day shows just horrific, horrific violence, kids’ clothes just basically disintegrating on them as the water hits them, kids backflipped in the air as the water hits their face or chest, kids writhing in pain as the Birmingham Fire Department and Birmingham Police Department keep the water hose right on them, at a distance of, again, 15 feet. Sometimes there was a girl — I will never forget this. There was a girl in Birmingham who was slid down the street by the power of the fire hose as she is just writhing in pain and screaming in terror, 50 feet, 60 feet, 70 feet. The camera crews just watched her pass. Then there were the German shepherds, like Walter Gadsden, the boy you referenced a moment ago.

The violence was so grotesque that there were literally war photographers who had been there, who had seen battle in World War II, and they said this was as bad as anything they had ever seen. There was a New York Times reporter by the name of R. W. Apple, who would later be famed, and he said he had never, across all of his years, in all of numerous war zones, he had never seen anything like the images out of Double D-Day, May 3rd, 1963. He had never seen that level of violence anywhere else in his life.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re going to go to break.

PAUL KIX: And so, that is what happened on that day. The courage that those kids showed that day, the faith that they showed, that these images would actually alter America, again, it led me to write this book, because I believe so fiercely that those 10 weeks, that week in particular, the week that we’re in right now, altered America forever, and for the better.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re talking to Paul Kix, author of You Have to Be Prepared to Die Before You Can Begin to Live: Ten Weeks in Birmingham That Changed America, and Janice Kelsey, longtime civil rights activist. She was 16 when she participated in the Children’s Crusade. We’re going to break, then coming back to talk more about this pivotal moment in history. Stay with us.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: “Alabama” by John Coltrane, recorded in 1963 after the September bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church that killed four little girls. This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman.

In 2013, I interviewed Sarah Collins Rudolph, who survived the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, September 15, 1963. She was 12 years old, hit with shards of glass, lost an eye, was hospitalized for months. Her older sister, Addie Mae Collins, who was 14, died in the blast. Sarah Collins Rudolph described what happened.

SARAH COLLINS RUDOLPH: Yes. I was in the ladies’ lounge when the bomb went off. You know, I remember Cynthia, Denise and Carole walking inside the lounge area and went in where the stalls was. So when they came out, Denise passed by Addie and asked my sister to tie the sash on her dress. And I was across from them at the sink. And when Denise asked her to tie the sash, and I was looking at her when she began to tie it, and then all of a sudden, boom! I never did see her finish it, finish tying it. So, all I could do was say, call out, “Jesus!” because I didn’t know what that loud sound was. And then I called my sister, “Addie! Addie! Addie!” And she didn’t answer me. So, I thought that they had — the girls had ran on the other side of the church where the Sunday school area was.

But all of a sudden I heard a voice outside saying, “Somebody bombed the 16th Street church!” And it was so clear to me, as though that this person was right there, but they was outside where the crater was, a bomb in the church — where it bombed the hole there. And all the debris came rushing in, and I was hit in my face with glass and also in my — both eyes. Well, when the man came in — his name’s Samuel Rutledge — he came in and picked me up and carried me out of the crater, and the ambulance was out there waiting. And they rushed me to Hillman Hospital, which they changed the name. It’s now UAB Hospital. …

So they rushed me on up to the operating room, and they operated on both of my eyes and took the glass from out of my face. And I had glass in my chest and stomach. So they operated on me. And when I went back to the room — and I stayed there in the hospital for about two-and-a-half months. But at that time, when they took the bandages off my eyes, the doctor asked me what do I see out of my right eye. I told him I couldn’t see anything out of my right eye. And when he took it off my left eye, all I could see was just a little light.

AMY GOODMAN: And, of course, you lost your sister, as well, Addie Mae Collins, your older sister. You were 12. She was 14. Did you feel you could not find a safe place? I mean, after all, you were bombed in a church, the place you went for sanctuary.

SARAH COLLINS RUDOLPH: Yes, you would think that going to church is really a safe place, but it wasn’t. You know, somebody that would put a bomb in a church and kill four innocent girls, you know, that’s just the work of the devil, because that shouldn’t never have happened. These girls was young, and we was waiting that day for a youth service. But by the bomb going off, we didn’t get a chance to attend youth service.

AMY GOODMAN: That graphic description of the bombing that happened four months — a little more than four months after the Children’s Crusade. We are continuing with Janice Kelsey, whose name was similar to Cynthia Wesley, one of the four girls who was killed, and so people called in condolences to Janice’s family, thinking maybe it was her. But she was active in the Children’s Crusade at the age of 16 in Birmingham, Alabama. And we’re joined by Paul Kix, author of You Have to Be Prepared to Die, that chronicles this pivotal moment in U.S. history. Janice Kelsey, after the protests — and you were arrested in this period 60 years ago?

JANICE KELSEY: Sixty years ago today, I was arrested for parading without a permit.

AMY GOODMAN: Did you ever get slammed by those water hoses, or were you arrested before?

JANICE KELSEY: I was arrested before the water hoses and the dogs.

AMY GOODMAN: To show, I think, how powerful your protest was, maybe if you could talk about those who criticized King and the other leaders, saying, “You shouldn’t put children on the frontline”? I think that was Malcolm X who said, “Real men don’t put their children on the firing line.” Robert Kennedy also criticized this strategy. Your response to them?

JANICE KELSEY: Well, we didn’t have any other choice. If our parents had protested, they could have lost their jobs. They would have gone to jail. There was no one to take care of us. But as Bevel pointed out to us, we really didn’t have anything to lose. We were getting a second-class education. We had all kinds of inequities put on us. And if we wanted that to change, we were going to be the change agents. We didn’t have anything to lose.

AMY GOODMAN: Paul Kix, if you could talk about a secret meeting that was held that included James Bevel and Dr. King, and then the unbelievable fundraiser that was held in Harry Belafonte’s apartment — who we just lost at the age of 96 — and what that meant for this movement?

PAUL KIX: So, in January of 1963, the SCLC had a secret meeting in Dorchester, Georgia. And they didn’t even invite all of the executive directors. Martin Luther King Jr. didn’t even invite his own father to this meeting, because they wanted to discuss what they called the most dangerous idea in the civil rights movement, and that was: Should we go to Birmingham?

And it was a huge risk, because the SCLC was broke. The SCLC had been criticized for years for ineffective leadership. The SCLC, just one year prior, had staged a massive and absolutely abysmal failure of a campaign in Albany, Georgia. The SCLC was sneered at by other civil rights groups at the same time, by the same token that they were sneered at by the press, be it Northern press or Southern press. And so, this campaign, they decided, we are — in that secret meeting in Dorchester, they thought, “Well, we are either going to break segregation in Birmingham, or we are going to be broken by it.” There was a real concern that the SCLC would die as a result of this. And in fact, there was a real concern that a lot of SCL members would actually die in Birmingham just for taking part. King even delivered mock eulogies in Birming — excuse me, in Dorchester, in preparation for what they thought Birmingham would be like.

And then, to — you asked, the other half of this is Harry Belafonte, and he played —

AMY GOODMAN: And so, that was Bevel, Shuttlesworth, King and Abernathy who had this secret meeting.

PAUL KIX: There were some — the accounts vary as to how many there were. It is somewhere between 11 and 15 people. There were a few other people there, as well. But, yes, there was a core group of people there. It was Fred Shuttlesworth. Wyatt Walker was there. James Bevel was there. King was there. Those are the four people that ended up being the four protagonists in my book.

And then, a secondary character, and hugely influential throughout the entire campaign, was Harry Belafonte. And if we flash forward a copy of months — this secret meeting happens in January of 1963. In late March of 1963, just days before Project Confrontation, as it was known, the Birmingham campaign — that was a secret name for it, Project Confrontation. Just days before that campaign launched, there was the just as large gamble as to how exactly they were going to try to finance it. And so they go to Harry Belafonte’s apartment in New York. And while they are there, Fred Shuttlesworth, who was kind of a regionally known civil rights activist — Janice would know who he was — but he was a Birmingham pastor who was absolutely fearless. And he wowed the donors there that night, with just basically stories of his courage and bravery and faith. And at the end of his speech, he said, “You have to be prepared to die before you can begin to live.” And that was the line that just amazed the donors. And that night in Belafonte’s apartment, they raised $475,000 for the Birmingham campaign, which is akin, I think, today — I don’t have the calculator in front of me, but something like $4 million in modern currency. And it was the largest-ever — it was the largest-ever fundraiser in the SCLC’s history, and that was the money that they used, orchestrated almost entirely by Harry Belafonte, to then go into Birmingham.

AMY GOODMAN: Finally, Janice Kelsey, we just have a minute, but I wanted to end with your voice. Sixty years ago today, you were arrested in the Children’s Crusade. Your thoughts at this moment and message about what’s happening today?

JANICE KELSEY: It’s very discouraging and frightening to see leaders in legislatures and governors who are trying to push back on the gains that were made due to the tremendous sacrifices that were made by young people 60 years ago, not just people like me who went to jail, but people like the four girls who were killed at church, and the four young men who were killed in the communities that same Sunday. A lot of blood sacrifice went forth in order for us to gain the measures that were gained. And it is frightening to see the big push by people in leadership positions to return to the way we were. And I’m hoping and praying that our young people will step up again and say, “No, we are not going back.”

AMY GOODMAN: Janice Kelsey —

JANICE KELSEY: That’s what those two legislators did.

AMY GOODMAN: Thank you so much for being with us, longtime civil rights activist in Birmingham, Alabama. And Paul Kix, You Have to Be Prepared to Die, his new book. Thank you.

READ MORE  Florida House Representative Michele Rayner, left, hugs her spouse, Bianca Goolsby, during a march at city hall in St. Petersburg, Florida, March 12, 2022. (photo: Martha Asencio-Rhine/AP)

Florida House Representative Michele Rayner, left, hugs her spouse, Bianca Goolsby, during a march at city hall in St. Petersburg, Florida, March 12, 2022. (photo: Martha Asencio-Rhine/AP)

“The outward expression is to show God’s love. That’s what I was taught,” said Jones, a Democrat. But, he said, “I have enough tears in my car to fill a lake.”

For Jones, who is gay, the past two years have been emotionally draining as Florida passed a flurry of anti-LGBTQ+ legislation.

More than 200 LGBTQ+ lawmakers across the country feel just like Jones, at a time when anti-gay and anti-transgender legislation is flourishing — as if they are under personal attack, and that they need to continually defend their community’s right to exist. The issue exploded into the national spotlight last week when Montana Republicans voted to bar Democratic Rep. Zooey Zephyr, who is transgender, from the House floor after a standoff over gender-affirming medical care for minors.

The ACLU is tracking nearly 470 anti-LGBTQ+ bills in 16 states, most with Republican-controlled Legislatures. Texas, Missouri and Tennessee alone account for more than 125 such bills; Florida has ten.

In the leadup to a possible presidential campaign, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis gained national attention for proposing and signing a bill to ban class discussion on sexual orientation and gender identity, which opponents have called “Don’t Say Gay” legislation. While DeSantis and other GOP leaders have increasingly waded into the culture wars, as part of their political toolbox, the emotions on both sides are ratcheted up.

“I actually have a policy of no longer crying in Tallahassee,” said Florida Rep. Michele Rayner-Goolsby. “I will cry when I go home.”

Rayner-Goolsby is a lawyer currently in a Master of Divinity program who was raised with a strong religious background. She’s also the first Black lesbian lawmaker in the statehouse to be out.

“I’m literally trying to exist,” she said. “The harsh things we’re saying are in defense of our life. The harsh things that they’re saying are to prop up a governor’s political ambition, and their desire and quest for power.”

In some cases, LGBTQ+ members who have deep faith are pitted against GOP members saying God doesn’t make mistakes, and that there are only two genders. There are also LGBTQ+ members with children who have faced derision and been told that children at large need to be protected from their community.

In Texas, there are three bills that would classify providing gender-affirming care to minors as a form of child abuse.

Other conservative states have followed Florida’s example with bills that restrict trans people’s access to gender-affirming care, bathrooms that correspond with their gender and LGBTQ+ books, as well as the ability to socially transition at school and to play sports at high school and college.

It’s put pressure on LGBTQ+ lawmakers who are encountering opposition, misunderstanding and even hate among their Republican colleagues.

North Dakota Sen. Ryan Braunberger, a Democrat of Fargo, said it’s “frustrating” and “maddening” to be a gay lawmaker in a Legislature where anti-LGBTQ+ bills are debated and most of his colleagues are voting to pass them.

When he was serving on a committee this session and conversation shifted to a bill prohibiting drag shows in public spaces, Braunberger said that a colleague wanted to make it illegal for people to host drag shows in their own homes.

“They want to eliminate members of the LGBTQ+ community from existing,” he said. “It’s what the extreme right is pushing for ... It represents a small but powerful part of the Legislature. And I fear that if we don’t stand up against it, that it will continue to grow.”

While LGBTQ+ lawmakers only compose a small fraction of state Legislatures, their numbers are growing, according to the group Out For America.

Statehouse debate about LGBTQ+ rights has increasingly descended into personal attacks and ran counter to the traditional practices of maintaining decorum and respect for one’s colleagues.

During a recent committee debate in Florida, Republican Rep. Webster Barnaby called trans people “demons,” “mutants” and “imps.” In Kansas last year, Republican Rep. Cheryl Helmer made headlines for saying in an email that she didn’t want to share a bathroom with a transgender colleague.

The targeted colleague, Democratic Rep. Stephanie Byers was the state’s only transgender lawmaker and decided last year to not seek reelection.

After Byers testified against a bill banning transgender athletes from girls and women’s sports, a Republican colleague pulled her aside to say he was sorry that Byers had to listen to bill supporters.

Still, he went on to vote for the bill.

The next day, Byers said the lawmaker told another member of what’s called the Kansas “queer caucus” that he couldn’t look himself in the mirror.

“It’s the same thing I think for every LGBTQ+ legislator, in no matter what state they serve in,” Byers said. “You don’t know what you can trust. When they say, ‘I like you, I love you and I’m glad you’re here,’ is that honest? Or is standing at the well and berating LGBTQ+ people, is that the honest person?”

For Florida Sen. Jones — the first Black gay lawmaker in the state — repeatedly hearing “I love you, but” from people he socializes with and works alongside is depressing, even more so when an anti-LGBTQ+ message carries religious undertones. Despite advice that he wouldn’t win reelection, he came out in 2018 and still won his seat.

While difficult, he said he is determined to fight hate with love.

“I pray more now than ever, and I believe in my heart that God loves me more than ever. I hate how they treat people, “ Jones said of Republican lawmakers crafting these bills. ”I hate what they’re doing to the transgender community, I hate what they’re doing to immigrants. I hate it all. But it is not my job to hate them. It is not my job to do anything but love them.”

READ MORE  The News Corp. building in New York. (photo: Michael Nagle/Bloomberg)

The News Corp. building in New York. (photo: Michael Nagle/Bloomberg)

It’s only when you get to the fourth-most cited reason, one chosen by about 2 in 5 Republicans who say they don’t plan to vote for Trump — in other words, a fraction of a fraction of the party — is the swarm of legal issues that surround the primary front-runner.

To an outside observer, this might be hard to fathom. Trump has already been indicted in Manhattan, is facing a defamation and battery trial brought by writer E. Jean Carroll, who alleges he raped her, and may well face charges at both the federal level and in Fulton County, Ga., related to his post-2020 election machinations. But all of this is fourth on the list of reasons Trump-skeptical Republicans aren’t interested in supporting him.

There’s one obvious contributor to this: Right-wing media is (and has long been) barely covering these issues. When they do, the tone often mirrors Trump’s — which is to say it’s dismissive.

Consider the lawsuit brought by Carroll, which is underway in a courtroom in New York. Carroll claimed in a book that Trump raped her in the dressing room at a New York department store in the 1990s; a change in New York that state law allowed her to file suit in 2022. Trump has denied the allegation.

When Carroll’s allegation first emerged in June 2019, CNN mentioned it on-air more than 130 times, according to closed-captioning data gathered by the internet Archive. MSNBC mentioned it more than 110 times. Fox News mentioned it less than 10 times.

This year, the pattern has been similar. CNN has mentioned Carroll more than 230 times and MSNBC more than 440. Fox News has mentioned her seven times.

(The animated charts in this article identify the search terms used to measure mentions. Since “E.” is only one letter, it was excluded from the above searches.)

This is similar to Fox News’s approach to the allegations against Trump involving adult film actress Stormy Daniels that emerged in 2018 — and were at the heart of Trump’s New York indictment this year. Back then, The Washington Post reported that Fox News’s prime time shows barely mentioned Daniels. That pattern has continued, particularly relative to the competition.

Daniels (you’ll recall, given that you read The Post) was the focus of an effort to bury a story about an alleged affair with Trump before the 2016 election. So was Playboy model Karen McDougal — who similarly didn’t come up a lot on Fox News.

There are some stories that Fox spends more time covering, like the search of Trump’s Mar-a-Lago event space in August. CNN and MSNBC still covered the issue more than Fox, but the gap was not as large.

Much of the Fox News coverage, of course, compared the Mar-a-Lago search to the investigation into Russian interference in the 2016 election or claimed it was aimed at hobbling Trump’s 2024 chances.

When it was reported that documents with classification markings had also been found at President Biden’s think-tank office and his home in Delaware, Fox News discussed it more than did CNN or MSNBC.

If special counsel Jack Smith determines that Trump’s efforts to retain documents with classification markings violated federal law, the heavily Republican Fox News audience has been primed to reject that determination as unfair or unwarranted.

If charges emerge in Fulton County, Ga., as seems likely, it may actually surprise the network’s audience. Since Trump was first recorded cajoling state officials to overturn the results of the 2020 election in January 2021, Fox News has mentioned the county in the context of Trump less than 100 times. CNN has mentioned it more than 800 times and MSNBC twice as often as CNN.

Over and over, the same pattern: Information about Trump’s legal travails is downplayed on the channel that, over the course of Trump’s presidency, was the most trusted outlet for his supporters.

That’s not likely to change over the short term. The ouster of host Tucker Carlson last week has left Fox News again vulnerable to poaching from far-right media outlets like Newsmax. Retaining a pro-Trump audience means increasingly downplaying or rationalizing his challenges rather than amplifying them.

And this pattern, very clearly, is a key reason Trump’s legal issues aren’t a primary motivator for those who are skeptical of his 2024 candidacy.

READ MORE  Ten states have rolled back child labor laws recently, with a federal bill to allow teens to work in one of the most dangerous industries. (photo: Worker.gov)

Ten states have rolled back child labor laws recently, with a federal bill to allow teens to work in one of the most dangerous industries. (photo: Worker.gov)

Ten states have rolled back child labor laws recently, with a federal bill to allow teens to work in one of the most dangerous industries

Bostwick’s son Cole, who had just turned 18, died in a logging accident in 2014 on a job site in Washington where his father, Tim Bostwick, was also working.

“Obviously that was a tragic situation, but somebody who does want to get into logging can and should be supervised by their parents,” Senator Jim Risch of Idaho, chief sponsor of the Future Logging Careers Act, said in an interview with the local Washington paper the Chronicle. “If a child is going to go into logging, what better way than to start with your family and having your family teach it to you?”

“Bullshit!” Bostwick told the Guardian. “It should open our eyes.

“One of the most dangerous jobs in the world and people want to put their children out there? Kids that age are not emotionally ready for something like this. They don’t have the mental faculties to drink alcohol, but they can go out there and make life-and-death decisions? I don’t think so. It’s dumb and dangerous,” she said.

The logging bill is just one of several efforts across the US to roll back child labor protections at a time when many employers are still struggling to fill jobs.

Backed by big business and lobby groups, politicians nationwide are pushing attempts to expand work hours for minors, expand the industries minors are permitted to work in, reduce enforcement and legislate sub-minimum wages for minors. These rollbacks at the federal and state levels are being proposed even as child labor violations have soared in recent years.

The logging industry is one of the most dangerous fields in which to work in the US, consistently leading with the highest workplace fatality rate in the nation.

“If this thing goes through, there are going to be a lot more families out there like ours. It’s been almost nine years and we still live it every day. We have to be careful of what music we listen to or what movies we watch, because it reminds us of Cole and the accident. We will never be right again. My whole family still has PTSD issues. My husband and I have been in and out of therapy since it happened,” added Bostwick.

“Losing an adult in the family is nothing compared to losing a child. Why, why, why would anyone want a child out there? There are plenty of adults who need those jobs too.”

Against this legislative drive, surveys show an already alarming surge in child labor violations. The number of children employed in violation of child labor laws has increased by 37% in the last year and by 283% since 2015, from 1,012 reported cases of children working in violation of child labor laws to 3,876 in 2022, according to a March 2023 report by the Economic Policy Institute (EPI).

“I think what we’re seeing in terms of the state push right now should be viewed as the latest multi-industry push to really wipe out regulation of child labor, not in one fell swoop, but that’s always sort of the end goal of the various pushes coming all at the same time,” said Jennifer Sherer, senior state policy coordinator for the Economic Analysis and Research Network (Earn) Worker Power Project, and author of the EPI report.

The 2023 Death on the Job report by the AFL-CIO labor federation noted that 350 workers in the US under the age of 25 died on the job in 2021, including 24 workers younger than 18 years old.

Ten states have proposed or passed legislation to roll back child labor protections in the past two years, including eight states so far in 2023.

Arkansas passed legislation in 2023 to eliminate age verification and parental or guardian permission requirements.

In Iowa, a bill was passed in 2022 to lower the minimum age of childcare staff and reduce staff-to-child ratios. The state’s Republican majority senate also recently passed a broader bill that enables minors to work in hazardous occupations and extends permitted work hours.

“This is part of a nationwide redefinition of childhood in the United States. It’s pushing Iowa kids decades into the past and it’s really concerning, because I think it’s going to take advantage of some of the most economically vulnerable kids in Iowa and around the nation,” said the Democratic state senator Liz Bennett.

New Jersey and New Hampshire also passed legislation in 2022 to roll back child labor protections. Missouri recently included an amendment to a house bill (HB188) that would expand work hours for minors. Legislation to relax child labor laws has also been introduced in Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, Ohio and South Dakota.

In addition to the legislation cited in the report, Nina Mast, an economic analyst at Earn and co-author of the EPI report, noted bills have been introduced in Maine and Virginia to create a sub-minimum wage for workers aged 14 to 17 years old. A bill in Georgia was proposed but failed this year to eliminate work youth permits.

Emails obtained by the Washington Post revealed much of the legislation aimed at rolling back child labor protection was drafted by the Foundation for Government Accountability, a Florida-based conservative thinktank that touts parental freedoms in advocating for the bills.

Business lobby groups are also pushing for change. “Could extra teen working hours help restaurants with the labor shortage?” the National Restaurant Association asked last year in a blogpost calling for Congress to pass the Republican-backed Teenagers Earning Everyday Necessary Skills (Teens) Act, which would lift restrictions on when and how much time teenagers can work.

The efforts, backed by business industry groups and conservative thinktanks, often contradict federal child labor law standards. In its report, the EPI argues the goal is to challenge federal standards at the local level in order to weaken or eliminate federal wage and hour standards.

The drive to increase child labor is being accompanied by a push to undermine oversight, said Sherer. She noted that the legislation in Iowa to roll back child labor protections also includes language to relax enforcement of any child labor violations.

“The most immediate problem and consequences, I think, created by the state rollbacks is the message that it’s sending, that on top of the already weak enforcement, it’s the state officials saying to the business community and to workers that they’re not going to be enforcing wage and hour or child labor laws,” said Sherer.

Democrats have proposed several federal bills to counter the trend and the Department of Labor and Department of Health and Human Services have proposed policies to strengthen enforcement of child labor violations and increase monetary penalties for violations. Opponents of the bills argue that enforcement is already inadequate and enforcement agencies haven’t been adequately staffed or funded to respond to the rise in child labor violations.

If these bills are not stopped, said Sherer, the long-term consequences for many children will be severe.

“There’s really extensive research in the public health and education world on why we have developed, over time, restrictions on work hours,” she said.

“Teens and high school students that get close to or exceed that 20-hour-a-week mark for paid labor during the school year end up in a higher-risk category, are less likely to complete high school, less likely to be in a position to pursue post-secondary education or training, and that puts young people on a path to fewer job opportunities and lower earnings for a lifetime. It’s actually very consequential,” said Sherer. “Even those pushes to extend work hours are a really slippery slope, and dangerous in terms of long-term economic outcomes for children and their families.”

READ MORE  MBS and Tim Cook, the CEO of Apple, at the Apple office in Cupertino, California, April 6, 2018. (photo: Bandar Algaloud/Saudi Kingdom Council)

MBS and Tim Cook, the CEO of Apple, at the Apple office in Cupertino, California, April 6, 2018. (photo: Bandar Algaloud/Saudi Kingdom Council)

All the ways Saudi Arabia’s cash powers tech startups and venture capital.

“The more I think about it, the more Saudi almost feels like a startup,” Adam Neumann, the WeWork founder, told the audience of the Miami conference hosted by the kingdom.

Venture capitalists Ben Horowitz and Marc Andreessen were pumped up, too.

“Saudi has a founder. You don’t call him a founder, you call him, ‘His Royal Highness,’ but he’s creating a new culture, he’s creating a new vision for the country, he’s got a very exciting plan to execute, and the people in the country are fired up to do it,” said Horowitz.

The whole scene at the Miami event, which was hosted by an offshoot of Saudi’s sovereign wealth fund, would have been unimaginable four and a half years ago.

In October 2018, Prince Mohammed bin Salman bin Abdulaziz al-Saud, or MBS as he’s often called, was determined by the CIA to have ordered the killing of journalist Jamal Khashoggi. Though Saudi Arabia had been a financial supporter of Silicon Valley, the killing led some American investors to speak out against MBS. That month, bold-faced names canceled their attendance at Davos in the Desert, a giant event in Riyadh hosted by the Future Investment Initiative Institute, a nonprofit linked to the Public Investment Fund, the sovereign wealth fund of Saudi Arabia and the sponsor of the Miami conference.

But five years later, the Future Investment Initiative Institute, which is essentially MBS’s private think tank, is hosting investors, CEOs, and former government officials at events in Saudi Arabia and the United States. The latest one in Miami featured guests like Jared Kushner, Steve Mnuchin, and Semafor cofounder Justin Smith, alongside the mayor of Miami. The event even drew out some celebrities, including DJ Khaled and A-Rod, and is scheduled to return to Florida next year.

A few days after the Miami event, Saudi Arabia published the names of dozens of venture capital firms, buyout funds, real estate investors, and startups that it’s funding in the US and internationally. The Public Investment Fund’s venture arm, Sanabil, is putting $2 billion a year into products we consume and tech we benefit from. It has direct investments in Bird scooters and AI startups Vectra and Atomwise. Plus there’s indirect money going through other venture funds into companies including Credit Karma, GitLab, Reddit, and Postmates, as well as the popular running shoes brand On or the military-tech darling and Pentagon contractor Anduril.

Among the previously undisclosed firms that had received Saudi funds: Andreessen Horowitz, whose portfolio companies include Instacart and SpaceX.

Two weeks later, Sanabil added major investors Tiger Global and Peter Thiel’s Founders Fund to its list of investments. Investment powerhouse Sequoia also was added to that list and then a week later was removed, with Sequoia China, a separate legal entity, taking its place.

“I was really surprised to see it. I think it’s disappointing,” said one influential Silicon Valley CEO, who asked to remain anonymous so as not to rankle colleagues. “I think, going forward, founders should ask for an answer. Most founders that I know have said things like, ‘I didn’t even think to ask because it seemed unimaginable to me.’”

But American venture capitalists might not care as much about optics these days. Capital markets are tightening in the US and Europe, which means there’s less money to go around in general. Meanwhile, the Biden administration is softening its stance on Saudi Arabia and even partnering with the kingdom on the Middle East broadly as well as energy policy and economic initiatives. There’s also a sense of urgency as China’s prowess as a tech competitor heightens. The convergence of these factors means that many new companies and established investing groups have turned to Saudi Arabia.

Vox reached out to the 60 venture capital and buyout firms and 19 startups that Sanabil has said it’s invested in to ask a simple question: How does this investment align with your company or firm’s values? None of them wanted to provide a comment.

Saudi money has become so prevalent in Silicon Valley. Why does everyone seem to think that’s okay? And why do they not want to talk about it?

How Saudi Arabia became a startup country

Back before 2018, it seemed like everyone in Silicon Valley was taking Saudi investments.

Though the kingdom was long understood as authoritarian, Silicon Valley was excited about the prospect of the young deputy crown prince known as MBS. He offered a reforming vision that New York Times columnist Tom Friedman touted as “more McKinsey than Wahhabi,” and called “his passion for reform authentic.”

MBS’s hyped-up reputation earned him a rousing welcome to the West Coast in June 2016 and April 2018. That included face time with Jeff Bezos, Bill Gates, and Mark Zuckerberg as well as exclusive visits to the headquarters of Apple and Google.

During those two years, MBS poured at least $11 billion into US startups, making it the industry’s largest single investor. Uber received $3.5 billion from Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund in 2016, after board member and former Obama adviser David Plouffe traveled to the kingdom. Electric car company Lucid received $1 billion and Magic Leap, the VR headset company, got $461 million through the fund.

Dozens of others received massive dollars through the SoftBank Vision Fund, which was funded through about $45 billion from Saudi’s Public Investment Fund. SoftBank is a Japanese telecom giant and multinational conglomerate that gave capital lifelines to startups like DoorDash, Slack, and WeWork. Through the first Vision Fund, Neumann’s WeWork received $4.4 billion, DoorDash got $680 million, and Slack benefited from a $250 million funding round led by the fund. Even Wag, the dog-walking app, got $300 million. The Wall Street Journal called the scale of investments “unprecedented.”

While people in tech may have taken stances against Saudi behavior, they weren’t exactly declining money from the Vision Fund, according to Margaret O’Mara, a historian of Silicon Valley at the University of Washington.

“If anyone was making those public statements, they did them quietly enough that they weren’t noticed by me,” she said.

Around that time, MBS had announced his intent to build a futuristic Saudi desert enclave called Neom. It would be a place for the young royal to show off his extravagant wealth through cutting-edge technologies and ostensibly sustainable design at a grand scale, thanks to $500 billion from the Public Investment Fund. Now under construction, the urban experiment includes a 110-mile-long city of skyscrapers called the Line, ski resorts and tourist beaches, and “climate-proof agriculture,” among other extravagant gimmicks, designed by starchitects. It’s all come under criticism for evicting indigenous residents, being wasteful to construct, and for containing potentially dystopian elements of a surveillance state built into Neom’s “smart city” infrastructure.

In September 2018, Open AI co-chair Sam Altman, Marc Andreessen, Apple designer Jony Ive, and former Uber CEO Travis Kalanick all joined Neom’s board.

The Khashoggi killing happened the following month, and much of Silicon Valley publicly stepped back from MBS. Altman publicly resigned from the board, and Ive’s name disappeared from it. Stars from Google and Uber dropped out of the October 2018 Davos in the Desert conference. The investors who did attend shielded their name tags from the press in attendance to avoid the embarrassment of supporting a ruler accused of ordering a brutal murder, though over time influential business people started to trickle back.

Since 2019, Saudi investors have participated in US deals worth a total of $7.4 billion, according to data from PitchBook. And while investment is slowing across the board, any money coming in is valuable.

How startups got comfortable with Saudi investments again

A combination of factors has brought Saudi Arabia back into the fold.

Candidate Biden on the campaign trail pledged to make MBS a pariah, but as high oil prices tested his global policies, the president traveled to Riyadh and gave the prince a first-bump in July 2022. It was an embarrassing about-face that showed that it was okay to do business with the country. So if President Biden can’t quit Saudi Arabia, why would Silicon Valley?

For all of the criticism coming from Congress and corners of the Biden administration about Saudi human rights, the US has largely continued to approve major sales of military technologies and weapons to Saudi Arabia. This American policy decision has given companies top cover and permission to follow.

“It’s a sensitive subject,” Jonathan Lacoste, the founder of Space.VC, said by text. “I’ve heard several VCs say that taking capital from any US ally or partner should be acceptable. … I’ve also seen VCs acknowledging it’s not worth the risk.”

Given the vicious policies that MBS has pursued, including domestic crackdowns and a disastrous war in Yemen, there are real perils.

“American businesspeople: Tread carefully. This is a country that does not respect human rights or the rule of law. And if you get involved, you have to be mindful of who your partner is,” says Michael Posner, a professor at NYU Stern School of Business, who previously served as Obama’s top human rights leader in the State Department. “It is a repressive government that stifles dissent, that arrests its critics, that doesn’t value free expression. The list goes on and on.”

Meanwhile, the credit crunch and lack of liquidity in markets in the US and Europe have made investments from Saudi Arabia welcome. “The firehose of money that came into tech over the last decade is now being tightened quite a lot,” says O’Mara. So, many large venture firms, with hyper-scaled assets under management and international aspirations, have turned to the Middle East sovereign funds for the sometimes hundreds of millions of dollars they need to fund per cycle.

The structure of such investing, wherein venture firms in practice don’t disclose their limited partners — that is, where the money comes from — gives firms like Andreessen Horowitz, 500 Global, and General Atlantic some plausible deniability, or at least distance from, their Saudi sovereign wealth investments. And that gives their portfolio companies even further distance and offers up the possibility that the startup founder can simply stay in the dark about where the money comes from.

Another important factor is that China is investing heavily in advanced technologies, and in response, Washington has centered much of its hawkish rhetoric on countering China’s influence worldwide. Silicon Valley is starting to view China through such a lens, too. Some US investors, who are committed to backing startups that would ultimately bolster US national security and qualitative edge, say that Saudi Arabia is the lesser of two evils at a moment when they see the China threat as particularly acute.

“There are times in history when we have the luxury to moralize and stand up for certain values, and there are times when you don’t have that luxury and you have to make compromises,” says Jake Chapman, managing director of the Army Venture Capital Corporation. In fact, a number of US military organizations and intelligence agencies have launched their own investment arms.

In an indication of how comfortable Saudi Arabia has become for investors, Goldman Sachs president of global affairs Jared Cohen visited the kingdom in February. Saudi Arabia is “in control of their own geopolitical destiny,” he posted on Linkedin. It was a not-so-subtle way to praise the kingdom and, in effect, MBS’s stewardship without using the crown prince’s name.

The art, film, and media industries have also followed this trend line on Saudi Arabia. The money is so ubiquitous that even Vox is touched by it. Penske Media Corporation received in 2018 a $200 million investment from the Saudi Research and Media Group, which is closely linked to MBS. Penske became a minority shareholder in Vox Media, this site’s parent company, earlier this year.

The vast distribution of Saudi money reaches some unlikely investors. Sanabil, the Public Investment Fund’s venture arm, released such a long list of investees on its website in April, and has continued to add several more news-making firms there, that that it was difficult to conceptualize the scope. Iconiq, the family office for many ultra-rich tech people, including Mark Zuckerberg, Sheryl Sandberg, and Jack Dorsey, was also on the list. So was the Peter Thiel-backed Valar capital investing group and Silverlake, a private equity firm whose portfolio of companies includes name brands Airbnb, Dell, and Waymo.

It gets even more complicated. The fact that Khashoggi was a Washington Post columnist has led to a standoff between MBS and the owner of the paper, Jeff Bezos, whose phone was reportedly hacked by the Saudi crown prince. Yet an early-stage venture firm that Bezos backs, Village Global, is one of the recently revealed recipients of Saudi venture dollars.

“There’s no way you could found a startup in this VC community and not be beholden to MBS or someone one step away from him,” said another tech CEO, who asked to stay anonymous to maintain ongoing relationships.

The moral hazards of Saudi Arabia’s investments endure

The Future Investment Initiative Institute held another gathering at the Pierre Hotel overlooking Central Park Manhattan last fall, where networking investors and NGO-types buzzed past the colorful murals of the Rotunda Room. Teams of comms specialists choreographed TED-inspired panels being live-streamed, quickly packaging them into memes and highlight reels, and Jared Kushner strode by with an entourage.

As waiters in white dinner jackets served freshly sautéed salmon and pasta, the international cadre of attendees were blunt about their host: Saudi Arabia is where the money is.

Though Silicon Valley once wrestled with the moral implications of Saudi dollars after the killing of Khashoggi, tech investors have clearly moved on. Horowitz, for instance, has been taking founders from its portfolio companies back and forth to what Horowitz described as a “startup country.” And some worry that the potential investments that might emerge from nurturing relationships through trips like these could help erase the stigma of the journalist’s murder.

Expect more visits. At the Miami forum, the Public Investment Fund’s governor said it’s likely to grow from $650 billion today to $1 trillion by 2025 and up to $3 trillion by 2030. With lending severely tightened in US and European banking systems, the financial and investing outlook for American VCs is distressing.

The return of US startups courting Saudi money also reinforces a certain narrative that MBS has created for himself — that he’s a reformer. The crown prince likes to highlight the splashy implementation of policy changes such as allowing women to drive, the opening of cultural spaces like movie theaters, and hosting major sporting events.

But, far beyond the killing of Khashoggi, the human rights situation in Saudi Arabia is abysmal. Executions have doubled under MBS, and many political prisoners remain incarcerated without due process.

Though Saudi Arabia has not been able to re-attract star power to the Riyadh summit that appeared in 2017, the year before Khashoggi’s killing, that may be beginning to change. MBS seems to know it’s better to stay on the sidelines, and the crown prince is so influential that he doesn’t need to be in the spotlight. It’s more effective to have Ben Horowitz and Adam Neumann praise his vision for Saudi Arabia.

Neumann might even expand his new real-estate startup, Flow, into the Neom urban experiment. As he put it in Miami, “It’s leaders like His Royal Highness that are actually going to lead us where we want to go.”

READ MORE  PFAS from firefighting foam at the the Van Etten Creek dam in Oscoda Township, Michigan. (photo: Jake May/AP)

PFAS from firefighting foam at the the Van Etten Creek dam in Oscoda Township, Michigan. (photo: Jake May/AP)

Partisanship has thwarted Congress’s attempts to limit PFAS, but a patchwork of state laws is pushing for their phase-out

Federal bills designed to address some of the most significant sources of exposure – food packaging, cosmetics, personal care products, clothing, textiles, cookware and firefighting foam – have all failed in recent sessions.

However, a patchwork of state laws enacted over the last three years is generating fresh hope by prohibiting the use of PFAS in those and other uses. These laws – mostly passed in Democratic-controlled states – are quietly forcing many companies to phase out the chemicals as they become illegal to use in consumer goods in some of the nation’s largest economies.

“We’ve seen some corporate leadership on PFAS, but the actual state policies that say ‘No, you have to do this’ – those are great incentivizers,” said Sarah Doll, director of Safer States, which advocates for and tracks restrictions on toxic chemicals at the state level.

PFAS are a class of about 15,000 chemicals often used to make thousands of consumer products across dozens of industries resist water, stains and heat. The chemicals are ubiquitous, and linked at low levels of exposure to cancer, thyroid disease, kidney dysfunction, birth defects, autoimmune disease and other serious health problems.

Though the Biden administration is devoting significant resources to limiting and cleaning up environmental PFAS pollution, it has no coherent strategy to address the chemicals’ use in consumer goods, and states have filled that void. Among those are laws banning their use in:

- Clothing/textiles. California, New York and Washington banned PFAS in clothing, while multiple states are prohibiting the chemicals’ use in textiles, such as carpets or furniture upholstery, or in children’s products like car seats and strollers.

- Cosmetics/personal care. California, Colorado and Maryland banned PFAS in all cosmetics and personal care products.

- Food packaging/cookware. About 10 states have prohibited PFAS in some food packaging, and several also bar it in cookware.

- Firefighting foam. At least 15 states have banned or limited the use of firefighting foam with PFAS because it is a major source of water pollution.

Maine has gone several steps further with a ban on all non-essential uses of PFAS, and the momentum continues this session in 33 states where legislation has been introduced. Vermont’s senate unanimously approved a ban on the chemicals in cosmetics, textiles and artificial turf.

The state policies may make it financially and logistically impractical for many companies to continue using PFAS, and their effects could reverberate across the economy.

“It would not make sense to not use the cancer-causing chemical in California and New York, but go ahead and use it in Texas,” said Liz Hitchcock, federal policy director at Toxic-Free Future, which advocates for stronger restrictions on chemicals.

Among a cascade of companies moving away from the compounds in some or all products are Patagonia, Victoria’s Secret, Target, Home Depot, Lowe’s, Ralph Lauren, Zara, H&M, Abercrombie & Fitch, Calvin Klein, Burberry, Tommy Hilfiger, McDonald’s, Burger King, Rite Aid, Amazon, Starbucks, Whole Foods, Taco Bell and Pizza Hut.

Sephora, Revolution Beauty and Target are among those in the cosmetic and personal care sector that have announced phase-outs of PFAS.

In December, 3M, perhaps the world’s largest PFAS producer, announced it would discontinue making the chemicals, in part citing “accelerating regulatory trends focused on reducing or eliminating the presence of PFAS”.

Companies widely use PFAS despite their myriad risks because they are so effective. The story of outdoor giant REI Co-op is emblematic of industry resistance to phase-outs.

In March 2021, a public health campaign began calling out a glaring inconsistency between REI’s virtuous marketing and use of PFAS in waterproof textiles: the company boasted of “responsible production” and advised its customers to “leave no trace” in the wilderness, but sold clothing waterproofed with dangerous PFAS chemicals that the campaign noted left a “toxic trail of pollution”.

But that changed in September 2022. California banned PFAS in apparel and textiles, and New York followed soon after. A February REI announcement that it would phase out the chemicals “in part to ensure wide industry alignment with new state laws regarding the use of PFAS” marked a major victory for public health advocates, and a similar story is playing out across the broader marketplace. REI did not respond to a request for comment.

Public pressure is also fueling the development. REI faced “immense pressure” from a coalition of more than 100 NGOs and 150,000 co-op members who signed a petition demanding the company eliminate PFAS in the 18 months ahead of the California apparel ban, said Mike Schade, who spearheaded the effort with Toxic-Free Future’s Mind the Store program. Even as REI held out, other companies that Mind the Store approached, like Wendy’s and McDonald’s, committed to eliminating PFAS.

The interplay among the campaigns, companies committing to eliminating the chemicals and state laws creates a potent “synergy” and sends pressure in both directions, Schade said.

“If we get more companies to act, that builds more political support for action at the state level to regulate and restrict harmful chemicals like PFAS,” Schade added. “At the same time, more states acting will create more pressure on businesses to take action ahead of state policies.”

California state assembly member Phil Ting’s bills to ban the chemicals’ use in food packaging and apparel drew surprisingly little resistance from industry, he said, which he ascribed to market momentum. Though most companies, like REI, were still using the chemicals, some major names like Levi’s, Whole Foods and McDonald’s had already announced phase-outs, the latter two amid pressure from Toxic-Free Future.

“It didn’t seem like government was leading, it seemed like government was supporting what had already started happening in the private sector, and that made it much more palatable for my colleagues,” Ting said.

Removing the chemicals and identifying, testing and developing safe alternatives for market production is a slow and difficult process that can take years. Before its March announcement, REI had said the “performance that customers expected” could not be matched by alternatives. Still, other companies managed to phase out the chemicals. Levi’s eliminated PFAS by 2018, but a spokesperson said the “challenge is significant considering that there are currently no equally effective alternatives to” PFAS.

Moreover, the supply chain is riddled with PFAS entry points as the chemicals are sometimes intentionally or accidentally added to materials upstream. PFAS are also used as lubricants that prevent machines from sticking to materials during the manufacturing process, and previous testing by the Guardian of consumer products highlighted how that can leave low levels of the chemicals on consumer goods.

That can mean that even manufacturers with good intentions may not know their products are contaminated with PFAS, said Christina Ross, a senior scientist with Credo Beauty, a “clean beauty” company. Credo never intentionally added PFAS to its products, and it has committed to removing unintentionally added chemicals by 2025. That involves working with suppliers throughout the supply chain, but Credo has found that while some care about the issue, others do not.

“We try to honor those suppliers who do by giving them our money,” Ross said.

But that is ultimately an inefficient and unreliable way for entire sectors to eliminate the chemicals, and Ross said it underscores the need for legislative bans. “In order to remove PFAS from any consumer products we have to stop the chemicals from being made in the first place,” she said.

That’s unlikely anytime soon at the federal level, where only two out of 50 stand-alone PFAS bills were approved last session, and sources say hyper-partisanship makes passing laws unlikely. States and the US House are passing the measures with bipartisan support, though the laws are largely enacted in Democratic-controlled states.

Observers offer two theories on why. The PFAS issue knows no socioeconomic or political boundaries – PFAS contamination is a problem for everyone, Doll noted, and it has hit constituents whom Republicans traditionally support, like farmers and firefighters.

Others say Republicans in most Democratic-controlled states don’t have a shot at stopping the bills, so they vote for the measure instead of angering constituents for no political gain.

Toxic-Free Future’s Hitchcock said she sells legislators on both sides of the aisle on PFAS legislation by pointing out that banning the chemicals makes sense financially. “We’re paying so much to clean up the mess, why not invest in not making the mess in the first place?” she said.

That thinking is partly behind the momentum in the states, but she added: “We can’t depend on just that – we need the federal government and Congress to act.”

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.