Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

The tool Russian mercenaries used to kill a Syrian army deserter and others has become a violent meme, similar to the Punisher logo in the U.S.

Among members of the Wagner Group and its supporters, the video of Bouta’s murder has given rise to a culture glorifying violence against noncombatants that is explicitly centered on the symbol of the sledgehammer. This cult is now being embraced by leaders of the group, including its founder Yevgeny Prigozhin, who have turned the sledgehammer into part of its brand. T-shirts and other merchandise depict sledgehammers alongside the Wagner logo, while both supporters and members of the group have taken to picturing themselves holding both real sledgehammers and replicas in photographs shared online, often while dressed in imitation of the killers from the footage.

Wagner now seems to be making the sledgehammer its official calling card. Last November, on the heels of a symbolic European Union resolution designating Russia as a state sponsor of terrorism, Prigozhin sent a sledgehammer smeared with fake blood to the European Union Parliament. That was followed by another incident in which a group of Russian ultranationalists threw sledgehammers at the Finnish Embassy in Moscow. Last month, Sergei Mironov, a Russian parliamentarian who heads an ultranationalist party, posted a photo of himself posing with a sledgehammer branded with Wagner’s logo atop an engraving of a pile of skulls, in yet another visual tribute to the group.

The macabre culture around Wagner Group comes at a time when it is ascendant within the Russian state and is making a strong recruiting push, appealing to foreign volunteers, including Americans, to join the group.

“A lot of the content that I see on Telegram and elsewhere is eerily reminiscent of neo-Nazi propaganda, which is an aesthetic that they seem to have copied,” said Colin P. Clarke, the director of policy and research at the Soufan Group, a global intelligence and security consulting firm that monitors Wagner activity online. “It makes sense given the audience they are trying to recruit, who are, essentially, for lack of a better word, sociopaths.”

Clarke said that Wagner’s recruiting pitch was in many ways reminiscent of the Islamic State, which had its own distinctive methods of carrying out executions and promised its fighters similar spoils — including sex slaves and property confiscated from minorities in Iraq and Syria — in exchange for their service. Similarly to the Islamic State, Wagner fighters have been accused of torture, murder, sexual violence, and looting in many areas where the group operates. Its brutality is increasingly seen as part of its sales pitch to potential clients, particularly in weak and failing states where governments are unconcerned with human rights abuses.

“As long as you go in and get the job done, no one is going to ask any questions about how you behave,” Clarke said, commenting on the culture promoted to recruits of the group. “That’s part of their brand right now.”

The creation of a cult of violence in wartime is not a uniquely Russian pathology. During the U.S.-led global war on terrorism, certain weapons, including tomahawks used by U.S. special forces to bludgeon enemies, became part of a culture glorifying death that took root among some members of the military and on the right-wing fringes of American society. The ubiquity today of the Punisher logo, popularized during the wars and now common among police officers domestically, is yet another legacy of the war’s cultural impact at home.

The U.S. also employed private military contractors during its conflicts, most notoriously the company formerly known as Blackwater, and many of them also engaged in crimes during the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Despite their brutality, however, none of them matched the political prominence of Wagner, which is rapidly becoming an integral part of Russian foreign policy. In addition to its role in Ukraine, where the group is said to field thousands of fighters, including prisoners convicted of serious crimes like rape and murder who have been offered a chance to fight in exchange for their freedom, Wagner mercenaries are now active across Africa and the Middle East. In those regions, the mercenaries enforce Russian foreign policy goals even as their private military contractor status provides a measure of plausible deniability. In countries like Mali, Libya, and the Central African Republic, Wagner mercenaries have been accused of participating in war crimes and exploiting natural resources as part of lucrative security arrangements with local leaders.

In a system where power is largely centralized around President Vladimir Putin, Prigozhin, an ex-convict who formerly worked as contractor providing lunches for Russian schools, has emerged as a political force in his own right, becoming the focal point for ultranationalist sentiments even more extreme than those represented by Putin and feuding with members of the military elite. In some quarters, Prigozhin and his group are even rumored to be possible challengers for power.

“The post-Soviet Russian state has always had two facets: the criminal element which Prigozhin represents, and the intelligence and military bureaucracy,” said Chris Elliott, a Ph.D. researcher at King’s College London focused on the study of political violence and war crimes. “Wagner becoming a more important tool of Russian foreign policy is really about the increased importance that criminal element has in pulling the levers of the state.”

In that light, the culture of the Wagner Group and its embrace of ultraviolence, with the sledgehammer as its symbol, sends a chilling warning about the trajectory of Russia under its present regime. The sledgehammer is not merely a symbol either. Late last year, the Wagner-linked Telegram channel Grey Zone posted a video of a defector from the group who had attempted to join Ukrainian forces being murdered with a sledgehammer in a manner similar to Hamadi Bouta. The video was posted along with an approving comment from Prigozhin, saying that the executed man had received “a dog’s death for a dog.” As the group ramps up its operations around the world, this is unlikely to be its last snuff film.

As one Russian oligarch reportedly put it, speaking on the growing culture glorifying violence around Wagner and its rise within a Russian state where criminals increasingly call the shots, “the sledgehammer is a message to all of us.”

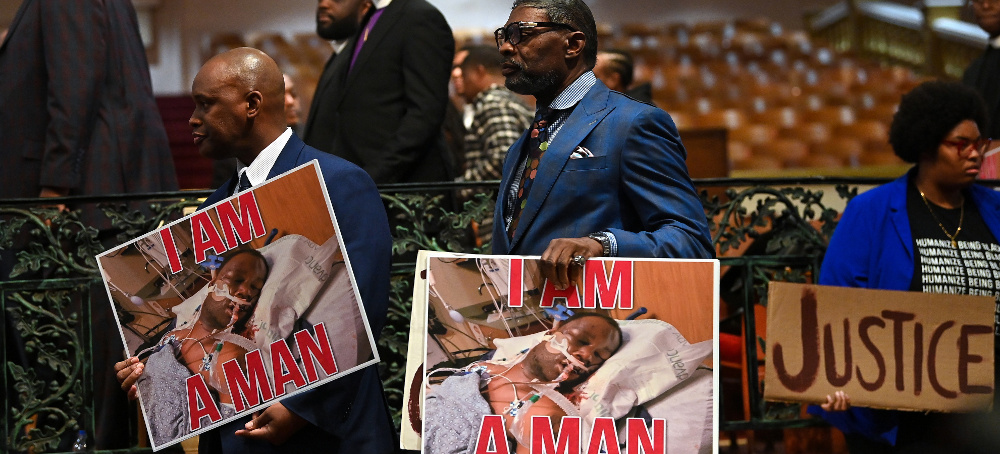

READ MORE  People attend a news conference in Memphis on Tuesday about Tyre Nichols, who died three days after he was beaten by police. (photo: Joshua Lott/The Washington Post)

People attend a news conference in Memphis on Tuesday about Tyre Nichols, who died three days after he was beaten by police. (photo: Joshua Lott/The Washington Post)

After Floyd was killed, demonstrators and officials called for police reform. What happened?

Testifying before Congress in June 2020, Cerelyn Davis, then the chief in Durham and president of the National Organization of Black Law Enforcement Executives, declared that the moment demanded nothing less than “policing reimagined.”

But more than two years later, that comprehensive approach remains out of reach. The policies Davis called for have not been adopted nationwide. And policing is once again confronting a crisis caused by video footage of officers using brutal force — this time in Memphis, where Davis is now the chief.

Officers’ beating of Tyre Nichols on a dark Memphis street illustrates a stark reality: The sweeping overhauls that demonstrators, public officials and some law enforcement leaders called for never materialized. Instead, there has been a patchwork series of reforms — some significant and far-reaching, others incremental and haltingly adopted — scattered across some of America’s thousands of local police departments, according to interviews with policing experts, former law enforcement officials, civil rights advocates, community leaders and others.

“There has been progress in different places, in different ways,” said Chris Magnus, the former police chief in Tucson and the ex-Customs and Border Protection commissioner. “But I can’t disagree that there are still some pretty big things that need to be worked on and improved.”

Even police unions, long viewed by reform advocates as a major impediment to change, expressed frustration. Jim Pasco, executive director of the national Fraternal Order of Police, blamed an apparent lack of supervision in Memphis for creating an environment in which the officers appeared almost nonchalant about their misconduct.

“I have no idea what the damn answer is,” Pasco said. He added that his group, one of the most prominent and influential law enforcement organizations, backed legislation on police changes that failed in the Senate two years ago and remains willing to negotiate.

“I always try to take a long view on these things,” he said. “But the fact is, taking that long view hasn’t really resulted in much progress.”

There have been some important advances, according to law enforcement analysts. New laws, policies and practices have been enacted across the country, some of them substantial. Since Floyd was killed in Minneapolis, states have passed hundreds of bills aimed at improving policing. Authorities added policies mandating body cameras and requiring that officers intervene when they see peers using excessive force. Some departments have tried to have mental health professionals, not armed police, respond to calls about people in crisis.

Yet at the same time, since Floyd’s death, police have also shot and killed more people than they did beforehand. Fatal shootings by police have risen each year since 2020, and last year, police shot and killed nearly 1,100 people, according to a Washington Post database tracking such cases.

Congressional efforts to enact legislation requiring broader changes failed amid widespread Republican opposition. And with gun violence and homicides up in recent years, local authorities pumping more money into their police have, in some cases, turned to specialized units like the “Scorpion” team in Memphis that employed the five officers charged in Nichols’s death.

Minneapolis, where Floyd was killed in 2020, summed up the issue in miniature: After his death, the city was the epicenter of the debate over policing. Local officials pledged to dismantle the police force and replace it with a new public safety agency. Some of them later backed away from such a pledge, and the following year, with residents concerned about an increase in shootings and violence, voters rejected a proposal to replace the police with a new agency.

“The spike in homicides that we saw in many cities, I think it gets difficult for politicians and for city leaders to not want to embrace policing,” said Justin Nix, an associate professor of criminal justice at the University of Nebraska Omaha. “Minneapolis being ground zero was a perfect example. Politicians came out and made bold claims about how they were going to reimagine policing. Crime went up and they got cold feet.”

Nichols’s death in Memphis, like Floyd’s in Minneapolis, became a nationwide flash point in which policing tactics or uses of force spurred criticism and scrutiny. Memphis joined a roster of cities that, since 2014, has included New York, Chicago, Charlotte, Cleveland, Louisville, Baltimore and Ferguson, Mo., among many others.

For some observers, video of officers pummeling Nichols highlighted what they see as a core problem that has not changed despite the outrage ignited in these places and others again and again: Despite targeting specific policy changes, police and government leaders have yet to fully grapple with entrenched cultures of impunity and brutality within some departments.

“This is just basic, bad police culture,” said Georgetown University law professor Christy E. Lopez, a former Justice Department official who helped oversee the federal investigation into the Ferguson Police Department after an officer fatally shot Michael Brown, an 18-year-old, in 2014.

“We’ve known for a long time we have bad police culture,” Lopez said. “This just underscores the enormity of a problem that requires every state to work and every community to work on this. In some ways, we have to remake expectations of what policing is.”

While cases like Nichols’s death often spur nationwide debates, policing in the United States is a very decentralized profession. There are about 18,000 law enforcement agencies nationwide, most of them local police departments and sheriff’s offices, according to federal data. And the vast majority of these local departments are small, with three-quarters employing fewer than 25 officers, according to a 2016 federal survey.

Analysts say the sheer breadth of policing can affect how reform plays out, making it difficult to enact sweeping changes across such a large number of agencies. And different departments, as well as states, counties or cities, can have varying policies, mandates, requirements and approaches to the use of force, training and accountability.

Still, though there has not been any singular nationwide shift, there has been considerable work done on the local and state level, experts said.

“There has been quite a bit of change,” said Stephen Rushin, a law professor at Loyola University Chicago who studies policing. “People often … expect or want to see big, sweeping national action at the federal level. But policing is handled overwhelmingly by localities. So the changes that happen are often changes within departmental policies, with departmental manuals or general orders, within union contracts or state statutes.”

Since Floyd was killed, state legislatures have approved nearly 300 bills dealing with police reform issues, according to the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism at the University of Maryland. Those included measures limiting the use of chokeholds, creating new restrictions on when force can be used, and mandating body cameras statewide in places including Connecticut and Colorado. New Mexico scrapped qualified immunity, which shields police officers from being sued for violating people’s civil rights. In Maryland, lawmakers adopted widespread police accountability measures, imposing strict use-of-force standards and requiring body cameras.

Police-worn body cameras have been touted as a way to help officers and the public alike, though some departments that adopted them amid calls for reform later ditched them, citing the high cost of storing the data. The Memphis officers were wearing body cameras, and the videos fueled additional criticism and questions; they were recorded saying Nichols reached for their guns, something not captured on any footage.

Nix, the University of Nebraska Omaha professor, said that while body cameras are not perfect, they have been broadly beneficial.

Before body cameras, Nix said, when police used deadly force, it was typically “the officer’s word against the victim, and the victim is dead.” Studies have shown that using such cameras can reduce police uses of force along with misconduct complaints against officers, he said.

Some other changes have also been undertaken on a more local level, including some cities now sending mental health teams, rather than officers, in response to certain calls.

According to The Post’s database of police shootings, about 1 in 5 of these fatal shootings involve people struggling with mental illness. Cities including Albuquerque, Orlando and Denver have begun sending specialized teams to respond to calls about people in crisis, following on the heels of a similar program in Eugene, Ore. The results have been promising: A study found that Denver’s program led to a drop in certain crimes there during a six-month period.

These efforts have unfolded while deadly police shootings have climbed nationwide. While the videos in Minneapolis and Memphis did not involve officers opening fire, fatal shootings by police have driven protests again and again in communities across the country.

The Post began tracking fatal shootings by on-duty police in 2015, the year after a White officer shot Michael Brown, a Black 18-year-old, in Ferguson, sparking unrest and a nationwide debate over how police use deadly force.

Most people shot and killed by police have been armed, The Post’s database shows, and the overwhelming majority of shootings are deemed justified. In many of these cases, defenders of police have said officers feared for their lives while confronting people armed with weapons, usually guns.

Despite the intense push for police reform that swelled in 2020, police that year shot and killed 1,019 people, the highest annual number since The Post began tracking shootings. Then the number climbed in 2021 to 1,048 people, reaching a new high, and it rose again in 2022, when police shot and killed 1,096 people. Memphis was one of the departments with an increase; police there shot and killed four people last year, up from one the year before.

Last year, protests erupted in Akron, Ohio, after police fatally shot Jayland Walker during a chase that began with a traffic stop. In Columbus, an officer shot and killed Donovan Lewis while officers were there to arrest him. In Minneapolis, police shot and killed Amir Locke during a predawn no-knock raid.

While The Post has tallied fatal shootings for nearly a decade, and resources like Mapping Police Violence as well as Fatal Encounters track shootings along with other deaths, there is still no comprehensive data available on numerous other uses of force.

There is no nationwide data tracking how often police shoot people who survive, for example. Last year, The Post and Berkeley Journalism’s Investigative Reporting Program found that between 2015 and 2020, officers in more than 150 departments shot and killed more than 2,100 people — and shot and wounded 1,600 others, suggesting a largely undocumented toll each year.

There has been at least one visible shift involving police use of force since Floyd was killed: More officers have been charged with murder or manslaughter for on-duty shootings, according to data tracked by Philip Stinson, a criminologist at Bowling Green State University.

There were 10 officers charged in such cases in 2018, Stinson’s data show, and 12 charged in 2019. That number climbed to 16 officers in 2020, 21 officers in 2021 and 20 officers in 2022, echoing earlier increases in such prosecutions brought in the aftermath of Ferguson.

Conviction rates in the cases after Ferguson remained largely unchanged from those brought beforehand, with most officers walking free or being convicted on lesser charges. Criminal justice experts and veteran lawyers say this is probably due to a combination of the law being on their side, with the shootings typically deemed justified and legal, along with jurors and judges generally having trust in police officers.

Stinson noted that the additional prosecutions accompanied an increase in fatal shootings by officers, so the percentage of cases leading to charges remains essentially unchanged.

“It seems like business as usual,” Stinson said of shootings and uses of force by police. “The culture of policing, or what I’d call the subculture of policing, does not change quickly. You can legislate policy changes at the federal level, at the state level, even the local level, but we’re just not seeing differences in police behaviors.”

Policing leaders also say they can struggle to get rid of officers who display poor behavior, something chiefs have attributed to powerful unions and independent arbitrators impeding efforts at discipline. Unions, meanwhile, have defended their actions by saying they protect officers from arbitrary or unfair punishment.

Magnus, the former Tucson chief, said chiefs’ efforts to oust troubled officers can be thwarted, even though “some of the same officers keep popping up on the radar over and over again.”

In his first address to Congress in April 2021, President Biden cited the “knee of injustice on the neck of Black Americans” — a reference to former Minneapolis officer Derek Chauvin’s role in Floyd’s murder — as he called on lawmakers to rally behind the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act, which the House passed the next month.

The bill aimed to establish a national database of police officers with records of misconduct, ban federal officers from using chokeholds, and require police in localities that receive federal money to wear body cameras.

The bill’s collapse in the Senate, amid GOP opposition that the legislation went too far in constraining police, forced a shift in the administration’s strategy, as Biden aides scrambled to negotiate a series of executive actions that would win support of civil rights activists and police unions.

In the meantime, the push for a strong federal hand in police reform fell primarily to the Justice Department, which under Attorney General Merrick Garland opened sweeping “pattern or practice” civil investigations into police departments in Minneapolis, Louisville and six other cities, while ramping up criminal prosecutions of individual officers, including those involved in Floyd’s death.

In fiscal year 2022, the Justice Department charged more than 60 law enforcement officials with civil rights-related offenses in more than 50 cases, federal officials said.

Civil rights activists have been frustrated at the pace of the federal efforts. The Justice Department’s investigations in Minneapolis and Louisville have been underway for more than 1½ years. Costly, court-mandated consent decrees ordering police changes in other cities have lasted up to a decade with mixed results.

The Louisville investigation, started after officers killed Breonna Taylor, a Black woman, in March 2020, could be wrapped up by spring, according to a person familiar with the case who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss an open investigation. In the meantime, the city has struggled to move the police department forward. Erika Shields, a reform-minded police chief hired in Louisville in early 2021, announced her resignation in November after voters elected a new mayor.

“I can’t say we’re seeing any real change yet,” said Sadiqa Reynolds, the former head of the Louisville Urban League. She added: “We’re not thinking big enough when it comes to how we are managing police. … We have to do something about the racism. At the core of this is that a Black life doesn’t mean as much.”

In 2022, with midterm elections looming and cities across the country contending with surges in homicides, Republicans painted Biden’s administration as soft on crime. Biden, who had previously distanced himself from activists’ calls to redirect police funding to social services and other programs, reiterated his stance that year, calling for $13 billion to put an additional 100,000 officers on the streets.

“We should all agree: The answer is not to ‘defund the police,’” Biden said in his 2022 State of the Union address. “It’s to fund the police. … Fund them with the resources and training they need to protect our communities.”

The Justice Department set up new programs to bolster collaborative reform with local police. At a policing conference in Los Angeles in April 2022 — 30 years after the acquittal of four officers in the beating of Rodney King set off rioting in that city — Justice Department officials announced the launch of a federal “knowledge lab” to share best practices on efforts to curb excessive force.

“For most of the 18,000 police departments in the United States, the Biden administration’s carrot approach won’t work,” said Georgetown University law professor Paul Butler, a former federal prosecutor. He suggested the administration take steps to tie federal grant funding to specific reforms from local police departments.

“This is a moment where the pressure has to be amped up to the maximum degree,” he said. Noting that Biden has invited Nichols’s parents to attend his State of the Union address on Tuesday, Butler added: “President Biden dare not say ‘fund the police’ in front of two parents who have just lost their son based on the violence of five police officers.”

The White House’s efforts to produce an executive action plan on police overhauls was delayed for months after police unions objected to proposed language citing “systemic racism” within the criminal justice system. After that language was altered, Biden announced his executive order on May 25, 2022, the second anniversary of Floyd’s death.

The plan has 92 measures, including the creation of national standards for the accreditation of police departments and a national database of federal officers with disciplinary records. The Justice Department is working to implement that order.

Amid the public outrage over Nichols’s killing, Democratic lawmakers, led by Sen. Cory Booker of New Jersey, have pledged to again introduce federal legislation on policing. On Thursday, Biden met at the White House with Booker and five other members of the Congressional Black Caucus, all Democrats, to discuss their efforts, telling them “my hope is this dark memory spurs some action that we’ve all been fighting for.”

Republicans are already balking, and there is little expectation in Washington of a deal, especially heading into a presidential election cycle.

Civil rights advocates who led the protest movement in 2020 said the past 2½ years have demonstrated the limits of the reform debate, saying the only solution is a major reduction in the role of police.

Maurice Mitchell, national director of the Working Families Party, denounced the Memphis officers for stopping Nichols in the first place, for what they said was a traffic violation. Police officers are involved in a lot of activities that have little to do with preventing or solving crime, he said, and changing how the public views their jobs could result in fewer chances of an escalation to deadly force.

There are, Mitchell said, “a lot of policy solutions that involve us reducing the police footprint so that these interactions never happen.”

READ MORE A mob of supporters of U.S. president Donald Trump fight with members of law enforcement at a door they broke open as they storm the U.S. Capitol Building in Washington, Jan. 6, 2021. (photo: Reuters)

A mob of supporters of U.S. president Donald Trump fight with members of law enforcement at a door they broke open as they storm the U.S. Capitol Building in Washington, Jan. 6, 2021. (photo: Reuters)

An investigator on the January 6 committee on how Trump supporters became “foot soldiers.”

You and I have been fumbling around with our Zoom call here for about seven minutes. Please tell me high-profile depositions didn’t go like this in the January 6 committee.

Sometimes at the beginning of the deposition, we had to spend 10 to 15 minutes dealing with witnesses trying to get their microphones to work. Or trying to get the screen to work. We’d have to pause in the middle to figure out why a screen froze or someone started echoing or their screen went blank, in the middle of very important answers. Somebody would just freeze and you throw your hands up in the air, but that's the world we were operating in.

That’s not the world I envisioned when I was watching (former White House lawyer) Eric Herschmann say, “I told him, ‘Get a great effin’ criminal defense lawyer, you’re gonna need it.’” But anyway, you spent most of your time looking at the actual attack, as opposed to the broad coup attempt?

We were divided up into color teams. I was on the “red” team, where we focused on the riot itself. But part of that was the domestic violent extremist groups, like the Oathkeepers and Proud Boys, Three Percenters. They were there planning to storm the Capitol no matter what happened. We also looked at the rally planners. I also looked at President Trump’s speech and how it came together. But mostly I looked at what you’d call foot soldiers in the game that the former president was playing.

The committee’s report is narrowly focused, mostly on Trump and his deep role in the riot and the coup. It sounds like you put yourself in the camp of people who say the committee missed a vital opportunity to address the deeper issues in American society that led to the insurrection?

I wouldn’t put myself in that camp. I think we were right to focus on President Trump. We didn't have the time or the resources to conduct a thorough, historical, sociological political sciences report for 50 years to explain all of the different things that have enabled someone like Donald Trump to become president in the first place, and then to convince so many millions of Americans that the election was stolen, and then push several thousand of them to storm the Capitol. It wasn’t as if we were ignoring these broader themes. Our hope is that historians, the public, reporters, will be able to keep answering those larger questions.

You’re concerned about the regular, everyday people who distrusted government so much they followed Trump and attacked. We have a long history of distrust in government in this county. But it doesn’t always result in a mob trying to stop the peaceful transfer of power, or the bombing of a federal building. So what’s different here?

You’re right, distrusting government isn’t new at all. But what’s changed that can make it worse? Clearly social media, the way algorithms amplify information, has warped and heightened distrust. If you lean conspiratorial, this model will keep pushing you further down a rabbit hole and eventually, you believe in QAnon. On top of that, income inequality is as bad or worse than in the Gilded Age. And there’s a lot of research that shows income inequality drives polarization and it drives people who feel left out to distrust what government is doing. Racial animus is layered on top of that, clearly. So there’s all these things happening at once to make people open to being hijacked by opportunistic politicians like Donald Trump.

The lazy media diagnosis of “economic anxiety” to explain Trumpism died a while ago. To be honest, I’d be surprised if that’s what your investigative work found was driving rioters.

I could see how people would react that way. That's not what I’m trying to do. But I don’t think we can afford to ignore people who do feel left out in that way. It’s just that the explanation for why they’re left out isn’t always as simple as “blue collar worker in Ohio lost a job to globalization.” It’s also very likely a rich person in Georgia, who harbors racial animus for a long time and found an outlet. And it was for someone who has seen the system as rigged, even if they are people who are benefiting from it.

A rich white person from Georgia with an authoritarian streak who manages to feel left out. I see what you did there. Marjorie Taylor Greene is a big coup backer, to put it mildly. By the way, how are you feeling about the various grand juries and special grand juries that are operating now?

That is the ultimate question. I am happy that law enforcement agencies are doing their job at the state level and it seems from my armchair view that the DOJ is moving forward. I have not been a prosecutor so I don't have much experience there. I am glad that our investigation sort of came to light a spark to get them moving perhaps a little faster.

Here’s the steal

Trump’s aides and allies have testified over and over that they knew he’d lost the 2020 election while he was lying about it in a bid to hold onto power. Now hear it for yourself.

The AP takes you back to Nov. 5, 2020, just one day after Wisconsin was called for President Joe Biden. That’s when the head of his Wisconsin campaign consoled his troops that Democrats had won a close one. In newly-obtained recordings, Andrew Iverson can be heard praising Democrats’ get-out-the-vote efforts. Then, this:

“Here’s the deal: Comms is going to continue to fan the flame and get the word out about Democrats trying to steal this election. We’ll do whatever they need. Just be on standby if there’s any stunts we need to pull,” Iverson said.

AP had called Wisconsin for Biden the day before. Later on the tape you can hear campaign operatives lamenting and joking about their fecklessness in reaching Black voters.

Of course, all this is just backdrop to Trump’s national campaign of lies that two months later would fuel his attempted coup. As for Iverson, he’s now an official in the Republican National Committee, which, as you’ll read below, is laying the groundwork to permanently weave stolen election propaganda into the party’s infrastructure.

Admittedly, Trump campaign aids admitting defeat and planning to lie while Trump dragged the country through an anti-democratic nightmare is hardly surprising anymore. It’s just nice to hear them say it in their own words.

T.W.I.S.™ Notes

- Scott’s plots

Rep. Scott Perry was apparently one of the most prolific coup plotters in Congress (pg 48). He also, totally coincidentally, happens to lead the House’s most powerful Trumpist GOP faction. Perry had his phone seized by the feds last August pursuant to a warrant as part of their coup investigation. They thought there might be evidence of crimes on it.

But they still haven’t unlocked and searched that phone, and they may not any time soon. Perry is locked in a largely secret dispute to keep the DOJ out of his phone, and now a federal appeals court has overturned a lower court ruling that would have let the feds in. Part of the dispute has to do with Perry’s contention that his communications are guarded by the Constitution’s “speech and debate” protections. Even the House’s “Bipartisan Legal Advisory Group” weighed in on Perry’s behalf, including Speaker Kevin McCarthy and Democratic Leader Hakeem Jeffries.

- Stay classified

FBI agents searched President Biden’s house in Rehoboth Beach, Delaware this week, looking for any stray classified documents that could be lingering there. According to Biden’s lawyer, none were found. Last week I was on the NPR show “1A,” where I talked about how journalists fail to do their jobs when they presume the public isn’t equipped to differentiate between Biden and Mike Pence’s behavior, and what Trump is suspected of doing at Mar-a-Lago (it’s here at about 26:10).

Meanwhile, two hired investigators who found a pair of classified documents at a storage facility for Trump appeared before the federal grand jury investigating the Mar-a-Lago case. That probe, now under Special Counsel Jack Smith, appears to be in full swing even while a separate special counsel investigates Biden.

- Matt fink

Rep. Matt Gaetz would like you to know that the three people who testified that he asked for a pardon after Jan. 6 all committed perjury under oath, while he is being truthful on TV.

- The Fifth element

“Very little,” Trump said when asked by an investigator what he did to prepare for his deposition in front of the New York attorney general last August. Here’s 22 minutes of Trump taking the Fifth Amendment in the lead-up to NY’s $250 million lawsuit accusing Trump, his family and his business of fraud against insurance companies, tax agencies and banks.

Can’t stop won’t stop

The Republican National Committee is looking to build a permanent election disinformation infrastructure on the foundation of Trump’s lies. A new RNC report proposes building out permanent “election integrity” operations in all 50 states, complete with poll watchers and “election integrity officers” assigned to amplify “concerns” about election fraud—not to combat the cause of those beliefs from within the party. Reminder from the Breaking the Vote guy you love to talk to at parties: Voters’ “concerns” about election fraud were hammered into place by a concerted and relentless lying campaign that Republicans largely support and that led to a deadly riot and attempted coup.

Stop the zeal

Read about the COVID-denying, election-undermining, Christian-nationalist revival organization that’s expanding to try to be an important part of Trump’s bid to recapture the imagination of the GOP base for 2024. ReAwaken America started with seed money from Overstock.com’s former CEO Patrick Byrne, who attended the now-infamous Dec. 18, 2020 Oval Office meeting with coup supporters. Pardoned and retired Gen. (what the hell happened to) Michael Flynn was there too, and he also happens to be a recurring star on the ReAwaken circuit.

Don’t miss the part where ReAwaken is planning a big event next month at Trump’s Doral golf resort.

“I’ve heard from a lot of people who will go onstage and put on the red hat, and then give me a call the next day and say, ‘I can’t wait until this guy dies.’” — Former GOP Rep. Peter Meijer, on Republicans’ conclusion that Trump will be the leader of the party until the very end.

Kari’d too far — Did losing GOP governor candidate Kari Lake go overboard when she tweeted out a claim that 40,000 Arizona ballots were invalid because of non-matching signatures? Election officials sure think so. Lake’s tweet included images of more than a dozen voter signatures. Newly-elected Secretary of State Adrian Fontes says that’s a felony, and referred Lake to the state AG for investigation. Fontes told this newsletter back in November that he was done coddling anti-democracy forces in his state. “Call the authoritarian an authoritarian,” he said.

“Totes Legit Votes” — Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis made a big deal out of his Office of Election Crimes before the 2022 election. Now the office is “a shambles,” according to some watchers in the state. Four of the 20 voter-fraud cases stemming from DeSantis’ photo-op arrests collapsed. One place where DeSantis didn’t send his voter fraud cops was The Villages, the Republican-leaning grand ville of grandparents in central Fla. And wouldn’t you know it, a fourth Villages resident has just pleaded guilty to voting twice in 2020. They were turned into authorities by an anonymous tipster calling themselves “Totes Legit Votes.”

VICE News’ Liz Landers happened to ask Florida Secretary of State Cord Byrd why DeSantis pumped up those 20 arrests while never mentioning the ever-growing list of voter fraud at The Villages. Check out his unsatisfying answer!

Pay troll before exit — Antisemitic artist and Trump dining buddy Ye paid a pair of notorious white nationalist trolls (and Trump dining buddies) Milo Yiannopoulos and Nick Fuentes tens of thousands of dollars to help with his yet-to-be-realized 2024 presidential campaign. Turns out the money was left over from Ye’s last tragically weird presidential bid. VICE News’ Tess Owen has the story from Ye’s campaign disclosures.

READ MORE  Immigrant children are led by staff in single file between tents at a detention facility next to the Mexican border in Tornillo, Texas, U.S., June 18, 2018. (photo: Mike Blake/Reuters)

Immigrant children are led by staff in single file between tents at a detention facility next to the Mexican border in Tornillo, Texas, U.S., June 18, 2018. (photo: Mike Blake/Reuters)

The U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) said on Thursday of the 998 children still separated, 148 were in the process of reunification.

Biden, a Democrat, issued an executive order shortly after taking office in January 2021 that established a task force to reunite children separated from their families under Trump, a Republican and immigration hardliner, calling such separations a "human tragedy."

The Trump administration split apart thousands of migrant families under a blanket "zero-tolerance" policy that called for the prosecution of all unauthorized border crossers in spring 2018. Government watchdogs and advocates have found the separations began before and continued after the policy's official start.

DHS said the task force's painstaking work of combing through "patchwork" information kept by the Trump administration on the policy had so far found 3,924, mostly Central American, children were separated at the border.

Many were located and reunified before Biden took office through a court process after the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) sued to halt the separation policy.

"The number of new families identified continues to increase, as families come forward and identify themselves," DHS said in a fact sheet on the work of the task force released Thursday. To date the task force has reunited 600 families.

DHS also said it has connected some reunified families to services like access to mental health resources. Reuters in 2022 profiled a Honduran mother that ended up homeless for several months in the United States after she was reunited her with her young daughters that she had not seen in years.

Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas told reporters on Thursday that there was still work to be done to fully address wounds inflicted by the policy. "That's what informs our efforts to extend behavioral health services as a component of reunification," he said.

READ MORE  A homeless man moves his belongings from an encampment in Concord, California, after city workers cleared the camp and removed structures from the property. (photo: Aric Crabb/Getty)

A homeless man moves his belongings from an encampment in Concord, California, after city workers cleared the camp and removed structures from the property. (photo: Aric Crabb/Getty)

Cities Are Spending More to Brutalize Homeless People Than It Would Cost to House Them

Luke Savage, Jacobin

Savage writes: "Few scenes are as emblematic of the barbarism of American capitalism as the now-routine 'sweeps' in which police round up homeless people and destroy their belongings. By some estimates, it would be cheaper to just provide them with housing."

READ MORE  Supporters from various social movements gathered to demand the release of the five water defenders. (photo: Esmeralda Ramos)

Supporters from various social movements gathered to demand the release of the five water defenders. (photo: Esmeralda Ramos)

The government of Nayib Bukele opens civil war wounds by arresting five water defenders linked to the historic community of Santa Marta, raising speculation about a possible reversal of the country’s metals mining ban.

El Salvador commemorated the 31st anniversary of the signing of the peace agreements that ended the country’s civil conflict (1980-1992) on January 16. The date—which is not recognized by the government of President Nayib Bukele—was marked by hundreds of protesters denouncing the prolonged state of emergency that has led to the arrest of tens of thousands of political opponents, union activists, youth for alleged ties to gangs and organized crime, and, more recently, five prominent anti-mining activists.

On January 11, the inhabitants of the community of Santa Marta in the municipality of Victoria, department of Cabañas, witnessed the arrests of Miguel Angel Gamez, Alejandro Lanez Garca, and Pedro Antonio Rivas Lanez, three respected community leaders. The Attorney General's Office and the National Civil Police executed the arrest warrant by means of a judicial order. Simultaneously, in the municipality of Guacotecti, Cabañas, Teodoro Antonio Pacheco, director of the local development organization Santa Marta Association for the Economic Development of El Salvador (ADES), and its legal advisor Saúl Agustín Rivas Ortega were also arrested. The prosecutors read the arrest and search warrant before the stunned residents of Santa Marta, who were alerted by the loud presence of authorities at 2:00 am.

Critics argue that the charges were hastily fabricated by the Attorney General’s Office with the intention to intimidate Santa Marta, ADES, and the wider environmental movement by arresting five prominent leaders of an organization that has achieved important social development and territorial defense against extractive projects in the impoverished Cabañas department.

Santa Marta’s Anti-Mining Legacy

Santa Marta is populated by ex-guerrilla combatants and families who fled to the Mesa Grande refugee camps in Honduras during the Salvadoran armed conflict. With historical ties to El Salvador’s revolutionary struggle, Santa Marta stands out in this mostly conservative department. Pacheco is the founder of ADES and a founding member of the National Roundtable Against Metallic Mining in El Salvador, a coalition that led the country’s historic anti-mining struggle and won the Institute for Policy Studies Letelier-Moffitt Human Rights Award in 2009. The other detainees are well-known community organizers and water defenders who played a crucial role on the frontlines of the successful fight to pass, in 2017, the first law in the world that prohibits metallic mining.

The five detainees have been charged with committing a murder in 1989 during the country's civil war and with illicit associations, a crime which populist President Bukele has widely employed to lock up tens of thousands of gang members since declaring a state of emergency on March 27, 2022. Under the ongoing state of exception, more than 61,300 alleged gang members have been detained, and more than 90 people have lost their lives in custody. Humanitarian organizations and the Office for the Defense of Human Rights have registered more than 7,400 complaints of abuses by the authorities and security forces. United Nations experts state that these measures violate human rights and lead to widespread arbitrary detentions.

The detainees have no relationships with gangs; for the last 30 years, they have worked with ADES implementing forest conservation projects, community organizing, sustainable agriculture, and water management programs. ADES community workers have been responsible for improving the quality of life of tens of thousands of people in Cabañas by bringing services and sustainable agricultural practices to isolated communities where government institutions have no reach, and by campaigning against environmentally destructive practices like the installation of garbage incinerators in their territory and the privatization of community water projects.

For 12 years, ADES was key in mobilizing local, national, and international support to stop the mining operations of the Canadian mining company Pacific Rim, which had gained influence with local municipalities, the police, judicial structures, schools, and even some churches to secure its operations. In 2009, “an intimidation campaign was unleashed against us,” says Vidalina Morales, President of ADES. “Anonymous death threats, criminalization, and in the worst case, four anti-mining activists including an unborn child were murdered. These assassinations have yet to be properly investigated.”

Community opposition to mining was widespread, says Morales, and the pressure compelled the Ministry of the Environment and Natural Resources to deny the company an exploitation license in 2008. Citing environmental and health concerns, the Ministry’s decision led Pacific Rim to sue El Salvador in 2009 before the World Bank’s International Centre for the Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) and demand $77 million in compensation. The demand increased to $250 million when OceanaGold acquired Pacific Rim in 2013. After seven years of litigation, the World Bank tribunal ruled in favor of El Salvador and ordered OceanaGold to pay the country $8 million in legal costs. The defeat of a multinational corporation at a pro-business tribunal inspired a final push of anti-mining mobilization that led to the 2017 mining ban. The prohibition was passed with multi-party legislative consensus and the support of rural community organizations, NGOs, university students, private sector organizations, and faith groups that included the Catholic Church hierarchy. It all started in Santa Marta.

Foreign Investment: The Driving Force Behind the Arrests

Given the detainees’ background, hundreds of national and international organizations have condemned the detentions as politically motivated amidst reports that the government is considering overturning the mining prohibition. In fact, the Salvadoran government is under enormous pressure to find new revenue streams since the country's sovereign debt is out of control, and the adoption of bitcoin as a panacea for the country's economic woes is not paying off.

Following the mining ban, the National Roundtable Against Mining has continued to demand stronger regulations to safeguard El Salvador’s already compromised ecological integrity. The Roundtable urges the government to implement key aspects of the ban such as environmental remediation for over 15 abandoned mining sites, justice for the families of the four anti-mining activists assassinated in 2009, and the establishment of a regional agreement on shared basins to avoid cross-border contamination arising from over 42 potential mining sites located on the border with Guatemala and Honduras.

El Salvador joined the Intergovernmental Forum on Mining in 2021, and a law was recently passed in the legislature to create a Directorate of Hydrocarbons. “The current government operates under a pro-mining logic,” says Luis González from the Salvadoran Ecological Unit (UNES). “We know that Canadian mining companies have their eyes on El Salvador and there are rumors that current free trade negotiations with China involve metal mining.” The unconfirmed inclusion of mining in the secret free trade negotiations is particularly troublesome, as China has become one of the main providers of foreign aid for the Salvadoran government and has offered to purchase its sovereign debt.

El Salvador is the most densely populated country in the region and one of the most vulnerable to climate change. According to a 2016 study from the Office for the Defense of Human Rights, the country could run out of water by the end of the century due to worsening droughts, and 90 percent of surface-level sources are already contaminated. Poor regulations on the industrial sector’s intensive use of water, lack of safeguards for the indiscriminate use of agrochemicals by monocrop agriculture, and irresponsible mining practices that have left unchecked acid drainage streams have contributed to contaminating the country’s water supply.

Organizations like ADES and the Santa Marta community have become the first line of defense, not only to promote environmental awareness and sustainable practices but also to organize communities to stop environmentally harmful projects. Prior to his detention, ADES director Antonio Pacheco had warned authorities and environmental groups that local community development organizations in Cabañas had received inquiries in recent months from suspicious individuals who had approached farmers offering multi-year leases to purchase land in former mining sites. Those early warnings may have led to the detention of Pacheco and the other leaders.

Bukele has utilized the state apparatus to decimate, incarcerate, and humiliate his political opponents. Through an army of anonymous internet trolls, the president also engages in smear campaigns against journalists who dare to question his decisions, says Omar Flores from the National Roundtable Against Metallic Mining. Recently, union members have been incarcerated for demanding unpaid wages in the municipality of Soyapango.

Condemning war crimes: A Double Standard

Victims of the war have demanded consecutive Salvadoran governments to pursue a policy of truth, justice, and reconciliation for war crimes. Attorney General Rodolfo Delgado’s narrative against the water defenders seems to manipulate that demand by claiming that the victims “are finally having justice.” Santa Marta members suggest that if the government were truly interested in prosecuting war crimes, it would investigate the dozens of complaints launched against the military by the community, particularly for the 1981 Lempa River Massacre in which 30 community members were assassinated and 182 disappeared during a raid led by the recently deceased Colonel Sigfredo Ochoa Pérez.

Most of the 75,000 civil war victims executed by the military, right-wing death squads, and paramilitary groups during the U.S.-backed dictatorship were civilians. Yet, Bukele’s government so far refuses to open military archives, as ordered by a judge in the infamous case of the Mozote massacre.

This double standard has led critics to argue that the government is utilizing a decades-old alleged crime to criminalize those who stand in the way of an imminent overturn of the mining prohibition. According to the legal defense team, the charges do not meet the minimum legal criteria to justify the arrests; prosecutors are relying on the hearsay of a protected witness, and have failed to provide material evidence that the accused are actually responsible for the murder. Still, at the first audience the judge dictated six months of preventive detention to allow the prosecution to continue its investigation.

“In its haste to please the dictator, the Prosecutor's Office forgot that the National Reconciliation Law of January 23, 1992, which grants amnesty to FMLN combatants and non-combatants, is 100 percent in force” tweeted Luis Parada, a prominent Washington-based lawyer who led El Salvador’s defense in the Pacific Rim/OceanaGold lawsuit.

International Solidarity Denounces the Arrests

Santa Marta, ADES, and rights groups fear that the community leaders could languish in overcrowded cells for months before formal charges are filed in court, a standard practice in the exception regime. “Our relatives, who are in their late 50s, are being held in isolation, with no access to healthcare, no visits allowed from family members, and limited five-minute time slots with their defense lawyers,” said a family member of one detainee, who wishes to remain anonymous.

Through sign-on campaigns, Salvadoran and international organizations have called on the national and international community to reject the political persecution of the water defenders. They also demand that the Salvadoran government drop the charges and urge legal representatives to uphold human rights. The response was immediate: on the day of the first hearing, a letter of support signed by 250 organizations from 29 countries was faxed to the desk of the judge designated to the case urging that the procedure take place outside the terms of the state of exception and that the detainees be released as they await legal proceedings. Statements of support also came from coalitions in South America, Spain, and the United Church of Canada.

Despite a constitutional prohibition on Salvadoran presidents serving consecutive terms, Bukele recently announced that he will seek reelection in 2024. The announcement has been widely criticized both in El Salvador and in the United States. These arrests only deepen concerns about the absence of judicial independence and respect for human rights and the rule of law.

Although our compañeros remain in custody, Santa Marta is not alone.

READ MORE  A gas flare is seen at an oil well site on July 26, 2013, outside Williston, North Dakota. (photo: Andrew Burton/Getty)

A gas flare is seen at an oil well site on July 26, 2013, outside Williston, North Dakota. (photo: Andrew Burton/Getty)

How poor methane rules are costing tribes and taxpayers.

Gas is wasted when it is released directly into the atmosphere through venting, or burned at the site of extraction by flaring, or when it leaks from aging or ill-fitting infrastructure. As a potent greenhouse gas with warming power 80-times that of carbon dioxide, methane is often released with additional air pollutants. Those emissions contribute heavily to climate change and poor healthcare outcomes for local communities.

Synapse Energy Economics, the consulting firm that conducted the analysis, found that 54 percent of the gas lost in 2019 was due to flaring, 46 percent to leaks, and less than 1 percent to venting. Researchers found that on federal lands, a majority of natural gas is lost to leaks while on tribal land, most loss is attributed to flaring. Overall, roughly $275 million worth of gas is lost through flaring.

Wasted methane shortchanges the royalties that tribal, state and federal governments collect for oil and gas production that often fund priorities like education, infrastructure and public services. According to the report, while tribal governments lost the most potential revenue, states lost $20.5 million and the federal government lost $21.3 million. Additional research showed that flaring rates on Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation lands atop the oil-rich Bakken formation were extremely high compared to public and tribal lands outside of North Dakota. Lost royalties from the MHA Nation totaled an estimated $19 million.

“We can’t continue to allow half a billion dollars’ worth of taxpayer-owned resources to go to waste every year,” Jon Goldstein, a senior director at the Environmental Defense Fund, said in a press release. “The Biden administration has a clear opportunity to step up with strong rules that stop waste and pollution from practices like routine flaring to protect the public interest. These resources should benefit priorities like education and infrastructure, not be released into the atmosphere to undermine our climate and health.”

The report comes in the wake of two proposed rulings from the EPA and the Bureau of Land Management aimed at reducing methane waste. Both proposals were issued last November and the EPA is accepting public comment on their proposal until February 13.

Goldstein said that the two proposed rulings target methane emissions from different lenses. The EPA ruling operates with a “pollution-oriented focus,” while the BLM ruling, which would target only federal and tribal lands, has a “waste-oriented focus.” Together, the two strategies offer complementary solutions to reduce emissions, but Goldstein says that a crucial, missing provision is to limit how much gas can be flared in the first place.

“There should be guardrails that narrowly define conditions flares are allowed in,” Goldstein said. “[Otherwise], it just becomes the cost of doing business. Oil and gas companies just write a check and continue to flare and waste.”

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.