Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

Putting our chips on the table

As Congress prepares for summer recess, average working Americans are facing increasingly hard economic times — including a likely recession (see here). Yet Congress has so far failed to provide most Americans with what they need to weather the storm — subsidies for childcare and eldercare, paid sick leave, an increase in the federal minimum wage, lower pharmaceutical costs, additional help with the next strain of COVID, and so on.

At the very same time, American corporations are lining up with their hands outstretched, seeking all sorts of special benefits. And there’s bipartisan support for giving them what they want.

Today I want to explain why corporations so often get what they want while average Americans don’t. It’s not simply that corporations bribe legislators with campaign donations, although that’s a big part of it. There’s another phenomenon at work that you need to know about.

Consider semiconductor chips. They’re the brains of modern electronics — embedded in everything from smartphones, radios, TVs, computers, video games, and advanced medical diagnostic equipment, to automobiles. As the world supply of almost everything tries to catch up with roaring post-lockdown demand, chips inevitably are in short supply.

This week, Congress is putting final touches on the CHIPS Act, which will provide more than $52 billion to companies that design and make semiconductor chips. The subsidy is demanded by the biggest chip makers as a condition for making more chips here.

It’s pure extortion.

You see, the world’s biggest chip maker (in terms of sales) is already an American corporation — Intel, based in Santa Clara, California. Intel hardly needs the money. Its revenue rose to $79 billion last year. Its CEO, Pat Gelsinger, got a total compensation package of $179 million (which was 1,711-times larger than the average Intel employee).

From the perspective of the United States, the problem is that Intel is not dealing with the current American shortage of chips by giving preference to producers in the United States, and it’s not keeping America on the cutting edge of new chip technologies. In addition to its facilities in the United States, Intel designs, assembles, and tests its chips in China, Israel, Ireland, Malaysia, Costa Rica, and Vietnam. And it sells them just about everywhere. (To add another layer of complication, many of Intel’s “American” customers don’t actually make their products in the United States. They’re headquartered in the United States but, like Intel, they design and make stuff all over the world.)

Obviously, Intel would like some of the $52 billion Congress is about to throw at the semiconductor chip industry — but why exactly should Intel get the money?

Among the other likely beneficiaries of the CHIPS Act will be GlobalFoundries. GlobalFoundries currently makes chips in New York and Vermont, but in many other places around the world as well. GlobalFoundries isn’t even an American corporation. It’s a wholly owned subsidiary of Mubadala Investment Co. — the sovereign wealth fund of the United Arab Emirates.

The point is, the nation where a chipmaker (or any other global corporation) is headquartered has less and less to do with where it designs and makes things or where its customers are located.

Every industry that can possibly be considered “critical” is now lobbying the U.S. government for subsidies, tax cuts, and regulatory exemptions, in return for designing and making stuff in America. But they’re lobbying in other nations, too.

It’s a giant global shakedown. India, Japan and South Korea have all recently passed tax credits, subsidies and other incentives amounting to tens of billions of dollars for the semiconductor industry, and the European Union is finalizing its own chips act with $30 billion to $50 billion in subsidies. Even China has extended tax and tariff exemptions and other measures aimed at upgrading chip design and production there. “Other countries around the globe … are making major investment in innovation and chip production,” says Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer. “If we don’t act quickly, we could lose tens of thousands of good-paying jobs to Europe [emphasis added].”

Who is “we,” Senator?

John Neuffer, the chief executive of the Semiconductor Industry Association (the Washington D.C. lobbying arm of the semiconductor industry) says the industry has been under “withering pressure” to build new manufacturing facilities to respond to the explosion of demand for chips, but he warns that chipmaking facilities are often 25 to 50 percent cheaper to build in foreign countries than in the United States. Why are they so much cheaper to build abroad? As he admits, it’s largely because of the incentives foreign countries have offered.

As capital becomes ever more global and footloose, it can play nation against nation to get the best deals in return for where it agrees to do what. Most people, by contrast, are rooted within particular nations, which gives them far less bargaining power.

This asymmetry helps explain why Congress is ready to hand over $52 billion to a highly-profitable global industry but can’t come up with even the $22.5 billion that the Biden administration says is necessary to cope with upcoming variants of COVID in the United States — for testing, therapeutics, vaccines, and essential treatments for the next generation of vaccines.

The reality is that global corporations have no loyalty to any nation. As the then-CEO of U.S.-based ExxonMobil unabashedly stated, “I’m not a U.S. company and I don’t make decisions based on what’s good for the U.S.”

If they are publicly owned, corporations have to be loyal to their shareholders by maximizing the value of their shares. But not even this guarantees that they’ll act in the best interest of the United States. Over 40 percent of the shareholder value of American-based companies is owned by non-Americans. There’s no reason to suppose a company’s American owners will be happy to sacrifice investment returns for the good of the nation, either.

Global corporations also have to obey the laws of the countries where they make or sell their stuff — which can cause problems when those laws or policies conflict with those of other nations. Last December, Intel was slammed by China for writing a letter to its suppliers, published on its website, stating that the corporation had been "required to ensure that its supply chain does not use any labor or source goods or services from the Xinjiang region” — as required by the United States (which has accused China of widespread human rights abuses in Xinjiang, home to the country's predominantly Muslim Uyghurs). Intel then deleted the reference to Xinjiang and apologized for the "trouble" it had caused, explaining that its commitment to avoid supply chains from Xinjiang was an expression of compliance with U.S. law rather than a statement of its position on the issue. (The apology caused Senator Marco Rubio to threaten to make Intel ineligible for CHIP Act subsidies. “Intel’s cowardice is yet another predictable consequence of economic reliance on China,” Rubio said. “Instead of humiliating apologies and self-censorship, companies should move their supply chains to countries that do not use slave labor or commit genocide.”)

This is not to dismiss the critical importance of semiconductor chips to the United States, but only to suggest that paying $52 billion in subsidies to global chipmakers to make them here is a peculiarly inefficient way of responding to that importance. The real question is what conditions the United States (or any other nation that subsidizes chip makers) should place on receipt of such subsidies.

It can’t be enough that a company merely agrees to make or design chips in America, because chip makers are already doing that. It can’t be that they’ll create more American jobs in chip making, because jobs in low-end fabrication that require little skill won’t build the technological capabilities of the U.S. workforce. And it can’t just be that the chipmakers agree to produce more chips in the United States, because additional production in the United States is no guarantee against future shortages in the United States. Remember, these corporations are global. They sell their chips around the world to the highest bidders, wherever the chips are produced.

If we want to tie the public subsidy to the public interest, we should demand that any chips produced in America, over and above those already produced here, focus on the highest value-added parts of chip making — design, design engineering, and high precision manufacturing — so Americans gain that technological expertise. And we should demand that in the event of chip shortages, the subsidized chipmakers give highest priority to their American-based customers — customers using the chips in products made in the United States, by American workers.

But what happens if every nation subsidizing chipmakers demands the same? Obviously, the chipmakers can’t grant most-favored-nation status to every nation. They’ll have to choose.

Also: How do we ensure that a big chunk of the $52 billion isn’t frittered away on shareholders and executive pay — as has been the case every time the U.S. government has subsidized Wall Street banks? Perhaps make chip makers agree not to buy back their shares of stock or pay their executives more than 50 times the pay of their median workers, and also give the government partial ownership in the form of equity interest. As Senator Bernie Sanders (who is pushing these conditions in an amendment to the CHIP Act) has said, there’s no reason to socialize the chipmaker’s risks and privatize their profits. If American taxpayers are going to give the semiconductor industry $52 billion, we should get a return on our investment.

What do you think?

Four EU leaders traveled to Kyiv last Thursday to give their blessing to Ukraine's bid for candidacy. (photo: Reuters)

Four EU leaders traveled to Kyiv last Thursday to give their blessing to Ukraine's bid for candidacy. (photo: Reuters)

Ukraine is set to be approved as an EU candidate at a Brussels summit on Thursday, after the European Commission gave the green light.

Its ambassador to the EU told the BBC it would be a psychological boost for Ukrainians.

But Vsevolod Chentsov admitted "real integration" could only start when the war was over.

Candidate status is the first official step towards EU membership and France said this week there was "total consensus" on Ukraine. But it can take many years to join and there's no guarantee of success.

The Western Balkan countries of Albania, North Macedonia, Montenegro and Serbia have been candidate countries for years; in some cases for over a decade. Bosnia and Herzegovina applied for candidacy in 2016 but has still not succeeded.

As he arrived for an EU summit with Western Balkan leaders, Albanian Prime Minister Edi Rama said it was a good thing that Ukraine was getting candidate status, but Kyiv should be under no illusions: "North Macedonia is a candidate [for] 17 years if I have not lost count, Albania eight, so welcome to Ukraine."

Some members states are pushing for Bosnia to be given candidate status, although that is not expected to happen.

'Why should we wait?'

"We do not accept the idea of the queue," Ukraine's envoy told the BBC, arguing Kyiv's eagerness could set an example to other states.

"Every state has its road map, has its path. And if there is political will, if there is support of society [and] business operators to move forward to implement reform in a bold and fast way, why we should wait?"

Moldova's application is also recommended for conditional approval while Georgia is set to be turned down, although the European Commission said the country could belong to the EU in "due time". More than 100,000 people attended a rally on Monday night in the Georgian capital appealing for candidate status.

Several EU states have agreed to back Ukraine's candidacy, provided conditions are attached before accession negotiations can begin, including judicial and anti-corruption reforms.

Mr Chentsov has insisted some reforms can take place, even while the country is at war and not in control of its whole territory.

"We are not starting from scratch," he insists, pointing to work carried out since the EU and Ukraine signed an association agreement in 2014. But it would be "logical" to carry out bigger reforms once the situation on the ground became more stable, he added.

Some EU diplomats have previously voiced concerns that giving candidate status could offer Ukraine false hope.

French President Emmanuel Macron said in May that the prospect of membership was decades away and the Nato secretary general has warned the conflict could last years.

But Mr Chentsov said no-one had a crystal ball and he felt there was a will "to help Ukraine to get there".

Macron plan for broader EU community

As well as deciding on which countries should be given candidate status, EU leaders will also discuss food security in light of Russia's blockade of Ukrainian ports, condemned by the EU's foreign policy chief this week as a war crime. And they will assess President Macron's proposal for a wider "European Political Community".

According to draft summit conclusions seen by the BBC, the aim would be "to foster political dialogue and co-operation to address issues of common interest so as to strengthen the security, stability and prosperity of the European continent".

The French leader has suggested the community could include countries waiting to join the EU such as Ukraine and the Western Balkan states, or even those that have left, which would currently just include the UK. However, a number of EU diplomats have rejected the idea as half-baked. The UK left the European Union in 2020.

The Ukrainian ambassador did not dismiss the idea out of hand, saying: "Probably it will be something to consider for the EU, for the UK to join and we can sit at the same table together with the EU, Ukraine and UK."

UK Foreign Secretary Liz Truss has said her preference would be to build on existing structures such as the G7 and Nato.

Gasoline prices have been steadily increasing for the last few months. (photo: Getty)

Gasoline prices have been steadily increasing for the last few months. (photo: Getty)

You know the one: Drive past your local station, hoping to reach a spot with a slightly lower price.

I won big this weekend, passing up my local station’s $4.799 a gallon, pulling into Costco with half a gallon to spare and saving 20 cents per gallon.

I drove on feeling like a millionaire. But then I did the math: My fill-up would have been a whopping $3 more closer to home.

Expect a similar reaction nationwide if President Joe Biden persuades Congress to pause the federal gasoline tax for three months, an idea Biden announced Wednesday afternoon.

Federal taxes add 18.4 cents to a gallon of unleaded, and 24.4 cents for diesel. (In Texas, state taxes add 20 cents a gallon to either). The Associated Press calculates that at a national average of about $5 a gallon, people would save about 3.6%.

Let’s be clear about one thing: Every bit of savings helps, particularly for poorer families. Rapid inflation is crushing people, and there’s often not much they can do to use less fuel. Economists say, however, that such a modest cut might not even be noticed — especially cast against the rapid rise in prices since Biden took office.

This move is clearly meant to stem the tide of Americans’ anger and pessimism, which has Biden’s approval ratings at Trumpian levels and Democrats panicking about huge midterm losses in November.

And yet if Congress enacted his plan, the tax would be set to return at the end of September — a sudden spike right as voting gets underway in some states. Smart!

But Biden has to try something, because the blame-everyone-else strategy isn’t working. The White House is still trotting out the sad “Putin’s price hike” framing, as if people didn’t notice higher prices before the invasion of Ukraine. He’s attacking oil companies and asking them to reduce profits — without acknowledging that he all but invited them to take profits short-term by taking steps to curtail production long-term.

Next month, he’ll go to Saudi Arabia and implore it, too, to boost production. What happens if leaders of the state he condemned as a “pariah” asks: Why should we?

Energy prices underlie all inflation because of shipping costs. And the effect is cumulative; farmers are warning of possible food shortages if diesel prices keep rising. It’s one thing when people are stressed about the cost of feeding the family; it’s another if they can’t even get groceries.

Like most of the economy, gas prices are complex. No, it’s not all Biden’s fault. But people aren’t buying his blame games, and for many voters, weak steps like suspending fuel taxes merely emphasize that it’s time for someone with better answers.

In the meantime, keep that Costco card handy.

John Mellencamp, 70, has never stopped speaking his mind. (photo: Marc Hauser)

John Mellencamp, 70, has never stopped speaking his mind. (photo: Marc Hauser)

The "Small Town" singer criticized politicians over their response to gun violence, saying they "don't give a f*** about our children."

"Only, in America, can 21 people be murdered and a week later be buried and forgotten, with a flimsy little thumbnail, a vague notion of some sort of gun control law laying on the senators' desks," the 70-year-old musician and painter wrote on Twitter Tuesday, referring to the Uvalde, Texas, school shooting on May 24.

"What kind of people are we who claim that we care about pro-life?" he continued. Just so you know, anyone that's reading this... politicians don't give a f*** about you, they don't give a f*** about me, and they don't give a f*** about our children."

— John Mellencamp (@johnmellencamp) June 21, 2022

He concluded, "So, with that cheery thought in mind, have a happy summer, because it will be just a short time before it happens again."

Mellencamp's comments came on Tuesday as the Senate voted to advance a new bipartisan gun control bill. It would enhance background checks and give authorities up to 10 business days to review the juvenile and mental health records of gun purchasers under 21. Funding would also go to help states implement red flag laws as well as to expand mental health resources in communities and schools and boost school safety, among other things.

It would not include raising the minimum age to purchase an assault weapon from 18 to 21 or banning high-capacity magazines like the House of Representatives bills approved earlier this month.

The Uvalde shooter legally purchased an AR-15-style rifle on May 17 — one day after he turned 18. Three days later, he purchased a second rifle, and in between bought 375 rounds of ammunition. On May 24, he killed19 fourth graders and two teachers at Robb Elementary. The gunman also shot his grandmother in the face.

Mellencamp has long spoken out against gun violence, joining 200 other artists and music execs in 2016 in calling for gun reform in the wake of the Orlando nightclub shooting. Following the Uvalde shooting, he said on MSNBC's The Beat last week that news outlets should start showing the carnage of school shootings to open the eyes of those resisting reform.

"I don't know if you’re old enough, but I remember when Vietnam first started, and it was a conversation on the news," the father of five said. "But then, when they started showing dead teenagers, people did something about it, and the country united. I think that we need to start showing the carnage of these kids who have died in vain... If we don't show it, then they're dying in vain, because they're just going to pass more bulls*** laws like they're trying to get through now. Show us. Let the country see what a machine gun can do to a kid's head."

People protest in support of the unionizing efforts of the Alabama Amazon workers, in Los Angeles, California, March 22, 2021. (photo: Lucy Nicholson/Reuters)

People protest in support of the unionizing efforts of the Alabama Amazon workers, in Los Angeles, California, March 22, 2021. (photo: Lucy Nicholson/Reuters)

Civil rights groups and Palestine advocacy activists are call the ruling 'un-American.' (photo: Abed Al Hashlamoun/EPA)

Civil rights groups and Palestine advocacy activists are call the ruling 'un-American.' (photo: Abed Al Hashlamoun/EPA)

Advocates say ruling will ‘flip the First Amendment on its head’ and endanger the free speech rights of all Americans.

The Eighth Circuit Court ruled on Wednesday that boycotts fall under commercial activity, which the state has a right to regulate, not “expressive conduct” protected by the First Amendment of the US Constitution.

But advocates say laws that prohibit boycotting Israel, which have been adopted by dozens of states with the backing of pro-Israel groups, are designed to unconstitutionally chill speech that supports Palestinian human rights.

Such laws aim to counter the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movement, which pushes to exert non-violent pressure on Israel to end abuses against Palestinians that have been described by leading human rights groups, including Amnesty International, as “apartheid”.

“It’s a horrible reading, and it’s very inaccurate,” said Abed Ayoub, legal director of the American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee (ADC).

“I think this is a very un-American ruling and position. This will flip the First Amendment on its head. It’s shocking to see we’re living in a time where our courts are deteriorating our rights and abilities to express ourselves.”

The Arkansas case started in 2018 when The Arkansas Times, a Little Rock-based publication, sued the state over its anti-BDS law after refusing to sign a pledge not to boycott Israel in order to win an advertising contract from a public university.

The law requires contractors that do not sign the pledge to reduce their fees by 20 percent.

A district court initially dismissed the lawsuit, but a three-judge appeals panel blocked the law in a split decision in 2021, ruling it violates the First Amendment. Now the full court has revived the statute.

The Arkansas Times cited its publisher Alan Leveritt as saying on Wednesday that he will discuss “future steps” with the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), a civil rights group that helped the newspaper sue the state.

For its part, the ACLU called the ruling “wrong” and a departure “from this nation’s longstanding traditions”.

“It ignores the fact that this country was founded on a boycott of British goods and that boycotts have been a fundamental part of American political discourse ever since. We are considering next steps and will continue to fight for robust protections for political boycotts,” Brian Hauss, staff lawyer with the ACLU Speech, Privacy and Technology Project, said in a statement.

Judge Jonathan Kobes, who was nominated by former President Donald Trump, wrote in the decision that the state law does not ban criticism of Israel.

“It only prohibits economic decisions that discriminate against Israel,” Kobes said. “Because those commercial decisions are invisible to observers unless explained, they are not inherently expressive and do not implicate the First Amendment.”

But in a dissenting opinion, Judge Jane Kelly dismissed the notion that the law is rooted in economic concerns.

“By the express[ed] terms of the Act, Arkansas seeks not only to avoid contracting with companies that refuse to do business with Israel,” Kelly wrote. “It also seeks to avoid contracting with anyone who supports or promotes such activity.”

She said the law allows the state – in violation of the First Amendment – to “consider a company’s speech and association with others to determine whether that company is participating in a ‘boycott of Israel'”.

Such speech, which would be prohibited under the law, Kelly argued, may include “posting anti-Israel signs, donating to causes that promote a boycott of Israel, encouraging others to boycott Israel, or even publicly criticizing the Act”. It is not clear how many of Kelly’s colleagues from the 11-judge court joined her in dissent.

The appeals court’s ruling comes at a time when Americans across the country are encouraging economic and cultural boycotts of Russia over its invasion of Ukraine.

Republican- and Democratic-leaning US states have passed and enforced anti-BDS laws, discouraging businesses from boycotting not only Israel, but also illegal Israeli settlements in the occupied West Bank, occupied East Jerusalem and Syria’s occupied Golan Heights.

Most recently, many states have pushed to divest from Ben … Jerry’s parent company after the ice-cream maker pulled out of the occupied West Bank over human rights and international law considerations.

Free speech advocates say antiboycott laws carry potential effects beyond the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. For example, several states have introduced bills modelled after anti-BDS laws to penalise companies that boycott the fossil fuel industry.

Ayoub of ADC stressed the interpretation that freedom of expression can be suppressed for the benefit of the state’s economic interests enables significant infringements on the First Amendment.

He said he can see a scenario based on this ruling where a state would criminalise boycotting certain major corporations over ethical or environmental concerns.

“This is not just about boycotts. This is opening the door to strip away First Amendment rights of all Americans. It’s very frightening,” he said.

Multiple federal courts across the country have taken up and mostly blocked anti-BDS laws, but the appeals court’s ruling on Wednesday complicates the legal analysis on whether such statutes are constitutional.

Abed said the Supreme Court should settle the debate, but he noted the top court’s conservative majority has recently been moving to strip away – not protect – individual rights.

“You just have to put trust in a court that really has been [chipping away] at a lot of our rights lately,” he said.

Edward Ahmed Mitchell, deputy director at the Council on American Islamic Relations, echoed Ayoub’s remarks, saying the appeals court’s ruling “endangers the free speech rights of every American”.

“By ruling against The Arkansas Times, the Eight Circuit has broken with nearly every other court that has reviewed and struck down these unconstitutional, un-American anti-boycott laws,” Mitchell told Al Jazeera.

Jennifer Gomez drives past the Marathon refinery in Wilmington, California. (photo: Pablo Unzueta)

Jennifer Gomez drives past the Marathon refinery in Wilmington, California. (photo: Pablo Unzueta)

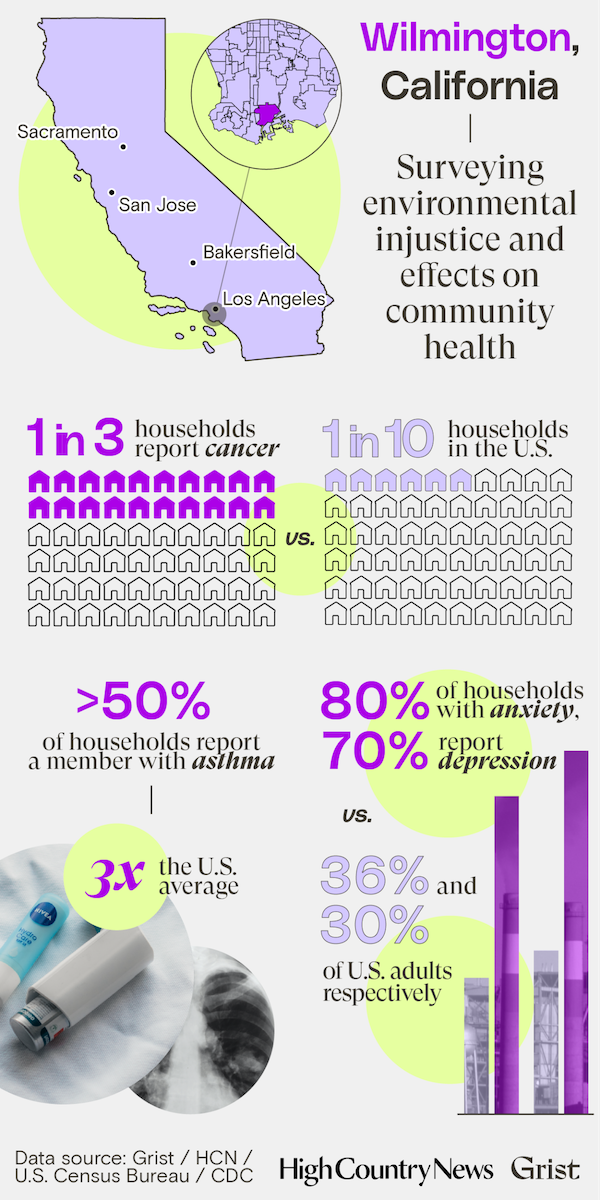

A new community survey exposes widespread cancer, asthma, anxiety, and depression in Wilmington, California.

There were so many disasters, she and her husband, Paul, both 73, told me. Was it the one in ’84? Or maybe the one in ’92 or ’96? Each fire painted the sky in different shades of black and orange. Paul believes the biggest one might have been later — closer to ’01, maybe, or even 2007 or 2009. He shifted uncomfortably in their living room; a recent procedure on his hip still made sitting difficult. “When that refinery blew, there were black dots everywhere,” Christina said, her short dark red hair framing her face, which was marked by lines from the stress. “All over the cars, the house, our fruit trees and patio furniture.”

“It was raining oil,” she said. She retired soon after that.

She had worked in the attendance office at Wilmington’s Banning High School. She remembered how often students came through, their faces flushed with sickness. “I’d see it in their notes,” she said. “Gone to the doctor, asthma, breathing issues, coughing — all the time. It was kind of heartbreaking to see these kids have to suffer as teenagers, and you could see it in their faces, how they didn’t feel well.” That was around the time her second-youngest grandchild was born.

Poor health, she says, is a painful but routine fact of life in her South Los Angeles community, an 8.5-square-mile tract surrounded by the largest concentration of oil refineries in California, as well as the third-largest oil field in the continental U.S., and the largest port in North America. A recent Grist investigation found that since 2020, Wilmington has experienced a dramatic rise in deaths related to Alzheimer’s, liver disease, heart disease, high blood pressure, strokes, and diabetes — all conditions known to be exacerbated by high levels of pollution.

Illness has spread through the Gonzalez home, too. Christina has been diagnosed with lung disease, lupus, and fibromyalgia, while her daughter, Jennifer Gomez, 42, has acute lymphoblastic leukemia, a cancer of the blood cells. Jennifer’s husband has had two heart attacks, and her teenage son has “been hospitalized more times than a 90-year-old” for multiple severe respiratory infections.

Eight members of the family reside in the house today. Paul’s mother, the first to move in, battled breast and skin cancer. Paul himself beat testicular cancer — twice. With his daughter’s diagnosis, that’s three generations of cancer in the same household. Since the early 1960s, the family has lived on Island Avenue, just one block from the Port of Los Angeles and about one mile from the Phillips 66 Los Angeles refinery. Jennifer jokes that a sane family would have moved, but the family knows it’s not that simple.

Housing in Los Angeles is more expensive now than it has ever been. Besides, there aren’t many places in Southern California where industry’s grasp is any looser. Riverside, located in California’s Inland Empire, is a prime example. The city used to be one of the most popular locations for Black and Latino families locked out of housing in Los Angeles, but today it’s the site of a major warehousing boom and has the country’s highest concentration of diesel pollution. “We can’t afford to sell, because where could we afford to buy?” Paul said. “It used to be that you could afford to buy out towards Riverside, but now that’s getting to be more expensive than LA. There’s no escape route.”

The federal Environmental Protection Agency, or EPA, says that air pollution can cause adverse health effects months or even years after initial exposure. “I know even if the pollution gets better and these refineries close, it is something that will stay within all of us for the rest of our lives,” Jennifer said.

Since 2000, more than 16 million pounds of toxic chemicals, primarily hydrogen cyanide, ammonia, and hydrogen sulfide, have been spewed into Wilmington’s air from industrial sites in the city, according to the EPA. That amounts to more than 2,000 pounds of chemicals every single day. Two-thirds of the chemicals were emitted by the Phillips 66 refinery.

In response to an inquiry from High Country News and Grist, a representative from Phillips 66 sent an email statement, writing that its Los Angeles refineries are striving to improve operations in a “safe, reliable and environmentally responsible” way and noting that company has employed $450 million in “emissions-reduction technology” since the early 2000s. The EPA’s Toxics Release Inventory data does not include another major source of pollution in Wilmington: The twin ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach are the largest in the nation as well as the single largest fixed source of air pollution in Southern California; collectively, they are responsible for more pollution than daily emissions from 6 million cars.

The walls of the Gonzalez home are decorated with family photos. When I visited Jennifer and Christina in April, Christina wore a shirt with the word “JOYFUL” written on it in five different colorful fonts. Our conversation was sobering, despite the presence of a six-foot-tall stuffed animal that the children adore. “You can’t go outside without hearing trucks from the port going down your street, seeing a cloud of smoke from one of the refineries filling the air, or tasting the sulfur,” Christina said. “I’ve gotten to the point where you could say I’m depressed.

“I get tired of calling the doctors to make appointments because I’m having breathing problems,” she added, “and then with the pandemic, being stuck inside watching my daughter (Jennifer) get so severely sick with leukemia.”

Just a few weeks after we spoke, Christina was hospitalized for a serious infection. She spent two weeks in the hospital and was then released for daily treatment at home.

This year, I moved back to Wilmington, where I grew up, after five years away. In part, my return was driven by a desire to write about — and on behalf of — my old hometown, an assignment that started with uncovering the hidden impacts of a century of environmental injustice. For three months, I canvassed the 1.5 square-mile area around the 103-year-old Phillips 66 refinery, an area that included my childhood home. My project, supported by Grist and the University of Southern California as well as by High Country News, focused on the physical, environmental and mental health impacts of air pollution. It came down to this: What is it like to live next to an oil refinery? Roughly 2,200 homes were initially contacted through in-person canvassing and postcards. Ultimately, 75 households, home to more than 300 people, opted to participate. The collected survey data has a 10 percent margin of error, equivalent to that found in the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey.

Here is what we found:

While I found the survey responses to be shocking, Alicia Rivera, a community organizer in Wilmington, reacted stoically when I shared the data with her. “None of this is unexpected,” said Rivera, who organizes with the Wilmington-based environmental justice organization Communities for a Better Environment. “In fact, it corroborates and legitimizes what we see every day, and it brings into question the ‘official’ data and stories we’re told from regulators.”

For more than a decade, Rivera has been an integral part of Wilmington’s community-organizing ecosystem, seeking accountability from both industry and regulators. Most recently, she was a lead organizer for a successful drive to phase out oil drilling in the city of Los Angeles. But it will take more than a few legislative changes to bring justice to the residents, she said.

“We struggle, and we struggle,” she told me, sitting in her organization’s office a few blocks from the port. “No one seems to understand how much frontline communities have put on the line — our health and lives — just for these polluting companies to profit.”

California is often held up as a model for climate policy, environmental legislation, and pollution regulation, but those standards are rarely reflected in frontline communities, said Hillary Angelo, a sociologist at the University of California, Santa Cruz. Angelo, who recently published a study analyzing climate plans in 170 California cities, found that local governments aren’t adequately implementing structural changes now.

“Communities on the front lines dealing with legacies of pollution, bad planning, and exclusionary practices are already confronting climate impacts directly,” she said during an interview earlier this year. Her research showed that local governments were more inclined to pass legislation with an obvious aesthetic appeal, such as tree-planting initiatives, rather than initiatives that took “histories of racial and economic injustice” into account.

“The inclusion of ‘green’ policies doesn’t seem to have any relationship to the needs in particular places,” she explained. In a place like Wilmington, it is “much harder to pass the important life-saving policies like improving public transit and affordable housing or funding contamination cleanup and renewable energy.”

Few of the Wilmington residents Rivera works with initially make the connection between the climate crisis and the issues plaguing their community. Once they do, however, it is an eye-opening experience. “Their biggest concern initially is the pollution from refineries, because it’s the more visible thing,” she said. “Then they realize its impact on their quality of life, their crumbling streets, the smells in the air. They start to put things together about how it is associated with their poor health.”

Our survey found that Wilmington’s industrial makeup hampers access to the outdoors:

Over the last four years, Rivera and other local organizers have created the Just Transition Fund to ease the impacts of life in an industrialized community. From President Joe Biden’s proposed Civilian Climate Corps to California’s Climate Jobs Plan, various attempts have been made to fund and otherwise support the nation’s shift to clean energy, but the programs tend to neglect the cumulative impacts of the country’s historical dependence on fossil fuels. The Just Transition Fund, Rivera said, would not only help fund training programs for clean energy workers and environmental remediators, it would also pump cash directly into frontline communities like Wilmington.

“We need accountability,” Rivera said, “and one way to do that is by using federal funds and corporate funds to help pay for things like health care and disability coverage in places paying the price for our pollution.”

Jennifer Gomez acknowledges that programs like Rivera’s would have an immediate positive effect on Wilmington. At the same time, however, they won’t erase the past, and they certainly won’t cure those already suffering from cancer in the community.

“I told my oncologist that if I survive, I want to fight back against the refineries and pollution,” Gomez wrote in her response to our survey earlier this year. “I firmly believe it’s why I got cancer, and why my best friend died of cancer, too, as well as so many other Wilmington residents.”

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.