Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

One day before the insurrection, the pro-Trump representative showed a man around the Capitol who would later declare, on video: “There’s no escape…We’re coming for you.”

On Wednesday, the panel released footage of the January 5 tour given by Loudermilk, noting that the participants appeared to take a keen interest in “areas not typically of interest to tourists: hallways, staircases and security checkpoints.”

Surveillance footage shows a tour led by Loudermilk to areas in the House Office Buildings, as well as the entrances to Capitol tunnels.

— January 6th Committee (@January6thCmte) June 15, 2022

Individuals on the tour photographed/recorded areas not typically of interest to tourists: hallways, staircases and security checkpoints. pic.twitter.com/Rjhf2BTdbc

In an accompanying letter sent to Loudermilk on Wednesday, the committee writes: “For example, the below image shows an individual appearing to photograph a staircase in the basement of the Longworth House Office Building while you speak with others nearby. [Another] image shows members of the tour you led also taking photographs of the tunnel leading from the Rayburn House Office Building to the Capitol. The behavior of these individuals during the January 5, 2021 tour raises concerns about their activity and intent while inside the Capitol complex.” As Esquire’s Charles Pierce notes, “The pictures accompanying the letter are specific and damning, unless you believe that Loudermilk’s congressional district is full of people whose hobby it is to collect photos of government staircases.”

Perhaps even more damning? An additional video released by the committee is said to show that same individual who photographed the staircase on Loudermilk’s tour headed to the Capitol on January 6, speaking to another man carrying a flagpole with a spear on the end who says, “It’s for a certain person.” The man from Loudermilk’s tour later says in the video: “There’s no escape [Nancy] Pelosi, [Chuck] Schumer, [Jerry] Nadler. We’re coming for you. We’re coming in like white on rice for Pelosi, Nadler, Schumer, even you, AOC. We’re coming to take you out and pull you out by your hairs…. When I get done with you, you’re going to need a shine on top of that bald head.”

This new video released by the January 6 Committee today is jarring.

— Ben Collins (@oneunderscore__) June 15, 2022

It's recorded by a man who toured the Capitol with Rep. Barry Loudermilk on 1/5.

He's talking to his "fearless leader" on 1/6, who shows a flag fashioned into a spear.

"That's for a certain person," he says. pic.twitter.com/Zqu9H0ikfP

As The Washington Post notes, “none of this proves that Loudermilk knowingly or even unknowingly helped those who stormed the Capitol on Jan. 6. Nor does the committee’s letter address whether the man in the video even entered the Capitol. But it lends at least some weight to some Democrats’ heretofore-unsubstantiated allegations that GOP members led ‘reconnaissance’ tours before Jan. 6,” and it certainly doesn’t look good. In concluding its letter to Loudermilk, January 6 panel chair Bennie Thompson writes: “The foregoing information raises questions the Select Committee must answer…. We again ask you to meet with the Select Committee at your earliest convenience.”

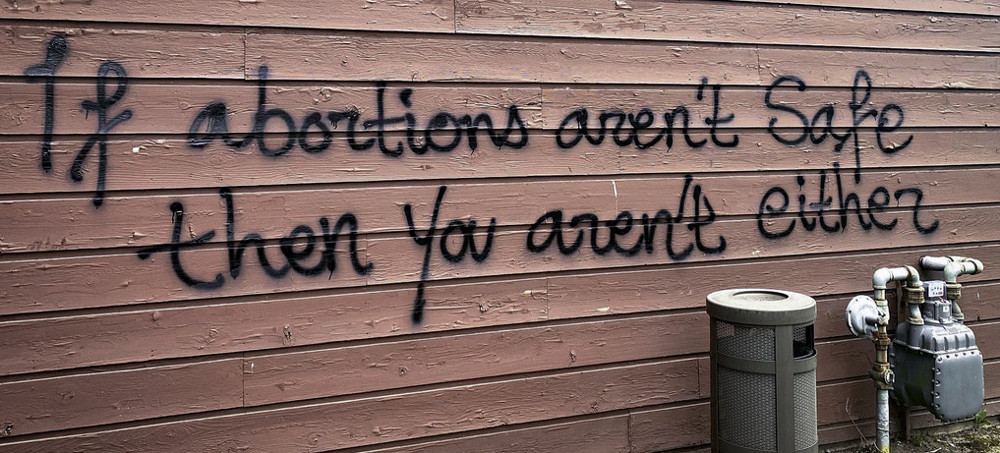

"If abortions aren't safe then you aren't either" is spray-painted on the exterior of a Wisconsin Family Action office in Madison, Wis., on May 8, 2022. (photo: Alex Shur/Wisconsin State Jounrnal)

"If abortions aren't safe then you aren't either" is spray-painted on the exterior of a Wisconsin Family Action office in Madison, Wis., on May 8, 2022. (photo: Alex Shur/Wisconsin State Jounrnal)

The attacks on anti-abortion centers express a necessary militant fury. But the conflation of militance with violence is a mistake.

Was this a false flag? Who but the extreme right, which had looked the other way while its terrorist armies murdered abortion providers, would besmirch the name of Jane, the Chicago collective that provided over 11,000 safe, illegal abortions before Roe v. Wade? This seemed the perfect tactic: A campaign of violence by pro-choice forces would reinforce the picture of abortion advocates as barbarians and justify draconian punishment of those who perform, facilitate, or have abortions. Come to think of it, had anyone in the world ever thrown a Molotov cocktail in the name of reproductive freedom?

Or was Jane’s Revenge a first — the anarcho-feminist descendant of the Weather Underground, the splinter of Students for a Democratic Society that bombed university and government buildings, banks, and other collaborators in the U.S. aggression against Vietnam during the 1960s and ’70s? The Weather Underground vowed to harm only property, not people. But inevitably, lives were lost to its botched heroics. Might Jane’s Revenge come to a similar end?

News coverage indicates varying skepticism. The mainstream media has mostly kept away from the story, while the Catholic press, the Washington Times, and Fox News were all over it.

In the May 15 edition of his daily podcast, “It Could Happen Here,” Robert Evans, who covers extremism, reviewed the language of a communiqué from the group and the source through which it came to him, and expressed confidence that Jane’s Revenge is what it says it is, not some right-wing imposter. Evans called the acts “ethical terrorism” — the destruction of “infrastructure” rather than the “unethical terrorism” that targets “civilians” — agreed with a guest that the Wisconsin attackers’ bomb was a “pretty good Molotov,” and pronounced the action “competent” and its messaging clear.

Among abortion rights advocates, Jane’s Revenge — whoever they are — has gotten predictably mixed reviews. “Our work to protect continued access to reproductive care is rooted in love,” the president of Planned Parenthood of Wisconsin said after the bombing in Madison. “We condemn all forms of violence and hatred within our communities.” DSM Street Medics, a health care collective in Des Moines, tweeted a communiqué from Jane’s Revenge on June 9. DSM’s comment: “we are in no way affiliated with these actions, but we applaud them.”

My feelings don’t exactly jibe with any of these. When news of the bombings broke, like many Americans I was dragging myself around, heavy with fear and despair over the shootings in Buffalo, Uvalde, and Tulsa, the certainty that Congress would do virtually nothing, and the likelihood that the Supreme Court would worsen the carnage by ruling gun regulations unconstitutional. The threat Jane’s Revenge scrawled on the walls of the wrecked buildings — If abortion isn’t safe, you aren’t either — only increased my dread. Was this the next step toward a Hobbesian war of all against all?

Yet I confess: Their rhetoric speaks to me. The characterization of their targets is refreshingly unvarnished. Agape, in Des Moines, is a “religious fake clinic that inflicts emotional, financial, and physical violence on people who need healthcare and support. They lie to, shame, and manipulate people into not getting abortions.”

Their analysis is correct. The Uvalde elementary school shooting “was an act of male domination and patriarchal violence, meant to make women, children and teachers live in fear. We know it is deeply connected to the reproductive violence about to be unleashed on this land by an illegitimate institution founded in white male supremacy,” reads a call to action posted on the group’s website.

My rage and impatience boil as hot as theirs. I too am exasperated by the mainstream’s “demure little rallies for freedom” — the May 11 demonstrations left me more depressed than invigorated — and sick of sitting “idly by while our anger is … channeled into Democratic party fundraisers.” I thrill to their language — wrath, fury, ferocity — and to their declaration that “we need them to be afraid of us.” While the barely disguised call to violence scares me, the call to emotion nails the problem, and the start of the solution: “Whatever form your fury takes, the first step is feeling it.” Author and activist Alix Kates Shulman once spoke of the exhilaration of feminist outrage — “the outness of rage.” When Jane’s Revenge outed my rage, I experienced relief from an anxiety I didn’t know I was holding.

But now what?

We don’t know whether the Jane’s Revenge actions were coordinated or independent of one another. The communiqué speaks of “the desperate need for those who can get pregnant to learn how to confront misogynistic violence directly.” It urges that the “unlearning of our self-containment … begin in the streets.” Once you feel the fury, the group exhorts, “the next step is carrying that anger out into the world and expressing it physically.” How do we confront misogynist violence directly? How should we express anger physically? Aside from “learn by example,” Jane’s Revenge suggests a DIY approach to tactics.

And the strategy? Evans, the podcaster, says the messaging is clear — but I think he’s referring to the texts. What about the bombing itself? To whom does it speak? For whom is Jane’s Revenge speaking? Whom do they want to attract? Whom are they willing to leave behind? Violence wins some friends and loses others. Beyond striking terror in the hearts of the enemy, what is the end game? Is there an end game? To me, the message is not at all clear.

“Night of Rage,” the name Jane’s Revenge gave the June round of “crisis pregnancy center” bombings, is obviously an homage to the “Days of Rage,” organized by Weatherman in Chicago during the October 1969 trial of the Conspiracy Eight. The actions included smashing the windows of cars, shops, and restaurants full of patrons, hand-to-hand combat with police, and a planned invasion of a draft board office. The Days of Rage were a bust: The turnout was small, the cops overwhelmed the protesters, and the draft board break-in was foiled. In the end, the actions did little but further alienate Weatherman from SDS and the Black Panther Party, whose Chicago chair, Fred Hampton, denounced the faction as “opportunistic” and “adventuristic” dabblers in “revolutionary child’s play.” Weatherman was “leading people into a confrontation they are not prepared for,” Hampton warned. And indeed, October 1969 presaged the group’s descent into more reckless — and lethal — violence.

Kathy Boudin, one of the Weather Underground’s most charismatic and brilliant leaders, embraced the belief that the wars in Indochina and against Black and brown freedom fighters at home would not end without armed struggle. In 1981 she drove the getaway van for a robbery of a Brink’s armored truck, in which her accomplices, members of the Black Liberation Army, shot and killed a security guard and two police officers. The Brink’s robbery was probably not meant to be a fatal act. Boudin did not carry a gun. She was not even on the scene when the heist took place. Yet she went to prison for two decades, where she spent endless hours struggling to understand and take accountability for what she came to see as a hideous error.

Like the Weather Underground, Jane’s Revenge knows that its movement needs to become more militant. Yet it makes the mistake of conflating militance with violence. How can the movement for reproductive justice become more militant without escalating our tactics to mimic those of our opponents — without meeting violence with more violence?

An example can be found in the other inspiration of Jane’s Revenge: Chicago’s Jane Collective. As the beautiful film “The Janes” shows, the women of the collective gave every client compassionate, respectful, and assiduously excellent abortion care. Jane charged as much as the patient could pay, including nothing. When they decided to form Jane, most of women were already involved in civil rights, anti-war, and feminist activism. Some had taken physical risks, facing bottle-throwing hecklers in civil rights marches in Chicago or traveling to Mississippi on the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee’s Freedom Rides to register African American voters. What they were about to do was no trivial transgression: Abortion was a felony in Illinois, carrying a penalty of one to 10 years per charge. But they were frustrated with feminist politics as usual. Like Jane’s Revenge, they yearned for direct action.

The Janes performed a necessary service, but they did not consider themselves a service organization. They saw themselves as practitioners of nonviolent civil disobedience. “There was a philosophical obligation on our part … to disrespect a law that disrespected women,” said one woman interviewed in the film. Another member called helping a woman end her pregnancy and move toward reclaiming her own life “a revolutionary act.”

For Boudin, “the Brink’s truck incident and her arrest provoked crisis and transformation,” wrote Rachael Bedard in the New Yorker, but it did not weaken her commitment to radical social change, which she realized in service and organizing throughout her incarceration. When she was finally released in 2003, Boudin continued to work for justice, until she was too weakened by the cancer that killed her last month. “The lesson she learned wasn’t ‘I shouldn’t dedicate my life to the struggle,’” Boudin’s son, Chesa, told Bedard. “The lesson she learned, definitively and through tragedy, was ‘Violence is not productive.’”

Like many Ukrainians trying to leave Russian-occupied areas, Andriy was forced to go through a process called filtration. (photo: BBC)

Like many Ukrainians trying to leave Russian-occupied areas, Andriy was forced to go through a process called filtration. (photo: BBC)

Andriy watched anxiously as Russian soldiers connected his mobile to their computer, trying to restore some files. Andriy, a 28-year-old marketing officer, was attempting to leave Mariupol. He had deleted everything he thought a Russian soldier could use against him, such as text messages discussing Russia's invasion of Ukraine or photos of the devastation in his city caused by weeks of relentless shelling.

"I'm screwed," he thought.

The soldiers, Andriy said, already had their focus on him. On that day in early May, when he first joined the queues for filtration in Bezimenne, a small village to the east of Mariupol, one of the soldiers noticed his beard. Filtration is how the process of scrutinising civilians wishing to leave Russian-occupied areas is known. The soldier, Andriy said, instantly assumed the beard was a sign that he was a fighter with the Azov regiment, a former militia in the city which once had links with the far right.

"Is it you and your brigade killing our guys?," Andriy was asked. He replied he had never served in the army, he started working directly after graduating, but "they didn't want to hear it".

As the soldiers went through his phone, they turned to his political views, and asked his opinion of Zelensky. Andriy, cautiously, said Zelensky was "okay", and one of the soldiers wanted to know what he meant by that. Andriy told him Zelensky was just another president, not very different from those who had come before, and that in fact, he was not very interested in politics. "Well," the soldier replied, "you should just say you aren't interested in politics."

They kept Andriy's phone and told him to wait outside. He met his grandmother, mother and aunt, who had arrived with him and had already been given a document that allowed them to leave. A few minutes later, Andriy said, he was ordered to go to a tent where members of Russia's security service, the FSB, were carrying out further checks.

Five officers were sitting behind a desk, three wearing balaclavas. They showed Andriy a video he had shared on Instagram of a speech Zelensky had given, from 1 March. With it was a caption written by Andriy: "A president we can be proud of. Go home with your warship!" One of the officers took the lead. "You told us you're neutral to politics, but you support the Nazi government," Andriy recalled being told. "He hit me in the throat. He basically started the beating."

Like Andriy, Dmytro had his phone confiscated at a checkpoint as he tried to leave Mariupol in late March. Dmytro, a 34-year-old history teacher, said the soldiers came across the word "ruscist", a play on "Russia" and "fascist", in a message to a friend. The soldiers, Dmytro told me, slapped and kicked him, and "everything [happened] because I used that word."

Dmytro said he was taken, with four other people, to a police station in the village of Nikolsky, also a filtration point. "The highest-ranking officer punched me four times in the face," he said. "It seemed to be part of the procedure".

His interrogators said teachers like him were spreading pro-Ukrainian propaganda. They also asked what he thought about "the events of 2014", the year that Russia annexed the Crimea peninsula and started supporting pro-Russian separatists in Donetsk and Luhansk. He replied that the conflict was known as the Russo-Ukrainian war. "They said Russia was not involved, and asked me whether I agreed that it was, in fact, a Ukrainian civil war."

The officers checked his phone again, and this time found a photo of a book which had the letter H in its title. "We got you!" the soldiers told Dmytro. Russia's president, Vladimir Putin, claims his war in Ukraine is an effort to "de-Nazify" the country, and the soldiers, Dmytro said, believed he was reading books about Hitler.

The next morning, Dmytro was transferred with two women to a prison in Starobesheve, a separatist-controlled village in Donetsk. He counted 24 people in the four-bunk cell. After four days and another detailed interrogation, he was finally released, and eventually reached Ukrainian-held territory. Weeks later, he still does not know what happened to his cell mates.

Back inside the tent in Bezimenne, Andriy noticed two other people with their hands tied behind them, who had been left in a corner while the officers paid attention to him. "They started to beat me way harder," Andriy told me, "everywhere". At one point, after a blow to the stomach, he felt as if he was about to faint. He managed to sit on a chair.

"I wondered what would be better," he said, "to lose consciousness and fall down or tolerate the pain further."

At least, Andriy thought, he had not been taken somewhere else, away from his family. Ukrainian officials say thousands of people are believed to have been sent to detention centres and camps set up in Russian-controlled areas during filtration. In almost all cases, their relatives do not know where they are being held, or why. "I [was] very angry about everything," Andriy said, "but, at the same time, I know it could've been much worse."

His mother tried to get into the tent, but was stopped by the officers. "She was very nervous. She later said they had told her that my 're-education' had started," Andriy said, "and that she shouldn't be worried." His ordeal, he told me, continued for two and a half hours. He was even forced to make a video saying "Glory to the Russian army!", a mockery of "Slava Ukraini!", the Ukrainian slogan.

The final question, Andriy said, was whether he had "understood his mistakes", and "I obviously answered yes". As he was being released, officers brought in another man, who had previously served in Ukraine's military and had several tattoos. "They immediately pushed him to the ground and started to beat him," Andriy said. "They didn't even talk to him."

Ukrainian authorities say Russian forces and Russian-backed separatists have carried out filtration in occupied territories as an attempt to establish residents' possible links with the military, law enforcement and even local government, as the invading forces try to restore services and infrastructure.

Men of fighting age are particularly targeted, checked for bruises that could suggest recent use of weapons, such as on the fingers and shoulders. Strip searches are common, witnesses say, including for women. Oleksandra Matviychuk, the head of the Center for Civil Liberties, a Kyiv-based human rights group, said the process, even when not violent, was "inhuman". "There's no military need for this... They're trying to occupy the country with a tool I call 'immense pain of civilian people'. You ask: 'Why so much cruelty? For what?'"

Maksym, a 48-year-old steelworker, said he was forced to strip naked while officers in Bezimenne checked even the seams of his clothes. He was asked whether he was from the Azov regiment or was a Nazi sympathiser - he denied being either - and why he wanted to leave Mariupol. "I said, 'Actually, it's you who are on Ukrainian soil.'" One of the officers, who he said were all Russian, reacted by hitting Maksym with the gun butt in his chest. He fell.

"I leaned my head on the ground, holding my ribs. I couldn't get up," he said. "It was very painful to breathe."

He was taken to what he described as a "cage", where others were being held. He noticed that one man, a weightlifter, had a tattoo of Poseidon, the Greek god, with a trident. The soldiers, Maksym said, thought it was the Ukrainian coat of arms. "He explained it to them but they didn't understand." Those detained in the "cage" were given no water or food, and had to urinate in a corner in front of everyone, Maksym told me. At one point, exhausted, he tried to sleep on the ground. An officer came in and kicked him in the back, forcing him to stand.

People would be taken to be interrogated and, when they returned, "you saw the person had been beaten," Maksym said. He witnessed a woman in her 40s lying in pain, apparently after being hit in the stomach. A man, who seemed to be around 50, had a bleeding lip and red bruises on his neck. Maksym believed he had been strangled. No-one in the "cage" asked or said anything to each other. They were afraid that FSB officers could be disguised as prisoners.

After about four or five hours, Maksym was released and allowed to leave Mariupol. Days later, he reached safety in Ukrainian-controlled territory, and went to a hospital to treat the persistent pain in his chest. The diagnosis: four broken ribs.

Yuriy Belousov, who leads the Department of War at the Ukrainian general prosecutor's office, said his team had received allegations of torture and even killings during filtration. "[It seems to be] a Russian policy which was designed in advance, and pretty well prepared," he told me. "It's definitely not just a single case or [something] done by a local military guy."

He acknowledged it was difficult to verify the cases, or estimate the scale of the violence. The Ukrainian authorities are unable to carry out investigations in occupied territories and most victims remain reluctant to share their stories, concerned that relatives in Mariupol could be targeted if their identity is exposed.

Vadym, 43, who used to work at a state-owned company in Mariupol, said he was tortured in Bezimenne in March. Separatist soldiers had questioned his wife after finding out she had "liked" the Ukrainian army page on Facebook, and restoring a receipt on her phone of a donation she had made to them. "I tried to stand up for her," he said, "but was knocked down." He got up, but was beaten once more. A pattern, he said, that happened again and again.

When Russian soldiers realised where he worked, they took Vadym to a different building. There, Vadym said, separatist soldiers asked him "stupid things" and started to beat him. "They used electricity. I almost died. I fell and choked on my dental fillings, which had come out from my teeth," Vadym said. He vomited and fainted. "They were furious. When I recovered consciousness, they told me to clean everything up and continued to give me electric shocks."

The torture, Vadym said, only stopped after Russian officers intervened. They carried out another round of questioning before finally freeing him. As Vadym left the building, he saw a young woman, who had been identified during the process as a court clerk, being carried out.

"A plastic bag was put on her head, and her hands were tied," Vadym said. "Her mother was on her knees, begging for her daughter not to be taken away."

Vadym's release came with a condition: he would have to go to Russia. About 1.2 million people in Ukraine, including thousands of Mariupol residents, have been sent to Russia against their will since the invasion began in February, according to Ukrainian officials. Russia denies it is carrying out a mass deportation, which would constitute a war crime under international humanitarian law, and says it is simply helping those who want to go. Ukraine rejects this claim.

Some of those sent to Russia have managed to escape to other countries and even return to Ukraine. How many, remains unclear. Vadym, with the help of his friends, moved to another European country - he did not want to reveal the exact location. He had lost some of his vision, he told me, and doctors said this was a result of head injuries from the beating. "I feel better now, but rehabilitation will take a long time." I asked him what he thought about filtration. "They separate families. People are being disappeared," he said. "It's pure terror."

Russia's defence ministry did not respond to several requests for comment on the allegations. The Russian government has previously denied it is carrying out war crimes in Ukraine.

Andriy and his family have now settled in Germany, after also having been forced to go to Russia. Looking back, he believes the occupying forces seemed to be using filtration to show their "absolute power". Soldiers, he said, acted as if it was a "type of entertainment", something to "satisfy their own ego".

I told him about another Ukrainian I had met, a 60-year-old retired engineer called Viktoriia. A soldier found out she had added a Ukrainian flag to her profile photo on Facebook, she told me, and the message "Ukraine above all."

She said that he pointed his gun at her and threatened: "I'll put you in the basement until you rot!" He then kicked her, she said. Viktoriia could not understand why he had acted like that. "What did I do? What right did they have?"

Andriy said he could not explain such behaviour. "I even try to justify the process somehow. Try to convince myself there's some logic."

But, he said, "there's no logic".

Mark Shields speaks during a taping of NBC's Meet the Press on Feb. 17, 2008, in Washington, D.C. The longtime PBS NewsHour commentator has died at age 85. (photo: Alex Wong/Getty)

Mark Shields speaks during a taping of NBC's Meet the Press on Feb. 17, 2008, in Washington, D.C. The longtime PBS NewsHour commentator has died at age 85. (photo: Alex Wong/Getty)

Shields died of kidney failure at his home in Chevy Chase, Md., NewsHour spokesman Nick Massella told NPR.

Before he retired in 2020, Shields provided thoughtful insights into the administrations of six U.S. presidents, on the Persian Gulf War, the Iran-Contra affair and 9/11. His tenure lasted for 33 years.

Shields was known for both his sense of humor and his expansive knowledge of American politics, Judy Woodruff, the anchor and managing editor of NewsHour said in a tweet announcing his death.

"I am heartbroken to share this..the @NewsHour's beloved long-time Friday night analyst Mark Shields, who for decades wowed us with his encyclopedic knowledge of American politics, his sense of humor and mainly his big heart, has passed away at 85, with his wife Anne at his side," Woodruff tweeted.

Woodruff also said in a statement: "Mark Shields had a magical combination of talents: an unsurpassed knowledge of politics and a passion, joy, and irrepressible humor that shone through in all his work. He loved most politicians, but could spot a phony and was always bold to call out injustice. Along with Jim Lehrer and Robin MacNeil, he personified all that's special in the PBS NewsHour."

The Wall Street Journal called Shields "the wittiest political analyst around" and The Washington Post described him as "a walking almanac of American politics."

"Mark radiates a generosity of spirit that improves all who come within his light," David Brooks, a New York Times columnist, wrote shortly after Shields retired. The two discussed politics together on NewsHour Friday evenings for nearly two decades.

Shields was a native of Weymouth, Mass., and graduated from the University of Notre Dame. After college, Shields went on to serve in the United States Marine Corps. Afterwards, he worked for several local and presidential races before embarking on his PBS career in 1988. Shields was also a columnist for several news outlets, including CNN and ABC.

He showed his famous sense of humor in a 2006 commentary for NPR's "This I Believe" series, writing: "I admire enormously the candidate able to face defeat with humor and grace. Nobody ever conceded defeat better than Dick Tuck who, upon losing a California state senate primary, said simply, 'The people have spoken ... the bastards.' "

A camera installed by D.C.'s Metropolitan Police Department is shown at 8th and O Streets, in Northwest Washington's Shaw neighborhood on Aug. 28, 2015. (photo: Astrid Riecken/Getty)

A camera installed by D.C.'s Metropolitan Police Department is shown at 8th and O Streets, in Northwest Washington's Shaw neighborhood on Aug. 28, 2015. (photo: Astrid Riecken/Getty)

From protesters to everyday residents, recently revealed documents provide a first-of-its-kind look into the invasive eye of Washington police.

Unbeknownst to the demonstrators, the police were also waiting — and watching. Stowed away in a secure room known as the Joint Operations Command Center, officers and analysts from the D.C. Metropolitan Police Department kept eyes on the news, activists’ social media accounts, and closed-circuit television feeds from across the district, according to internal MPD emails. The police were ready to funnel intelligence to officers on the ground, who were instructed to provide updates on protest activity back to the JOCC every half-hour.

Five months later, the MPD “activated” the JOCC again to monitor demonstrations against the Baltimore police’s killing of Freddie Gray, the emails show. In the lead-up to the protests, MPD analysts scoured social media for demonstration times and locations, as well as any possible indications of violence or civil disobedience, while officers on the ground sent photos of the gatherings. Then when marches started, the officers provided constant updates on where protesters were moving as the JOCC continued to gather intelligence, including on how demonstrators were monitoring the police presence and whether they suspected that there were plainclothes cops among them. (The JOCC had a practice of communicating with undercover officers, including to monitor protests.)

The MPD designed the JOCC as a surveillance control center. It contains more than 20 display monitors linked to around 50 computer stations, all connected to the MPD’s broad arsenal of intelligence data programs and surveillance sources. Launched in a rush on September 11, 2001, it was the MPD’s first “war on terror”-era infrastructure upgrade. Since then, the command center has served as a template for area police’s massively expanded domestic surveillance apparatus.

As a jurisdictional oddity and the site of the country’s most powerful institutions, D.C. contains more law enforcement officers — coming from local, regional, and federal agencies — per capita than any other major city in the U.S. The highly coordinated agencies have together built a complex network of partnerships, initiatives, and technology to surveil the district. The JOCC, for example, is accessible to the FBI, the Department of Homeland Security, and regional police intelligence hubs, in addition to the MPD.

For years, this sprawling web of surveillance has been shrouded in secrecy. Now, more than two decades into the frenzy of police monitoring of ordinary citizens, recently uncovered documents are revealing its scope and practices. (The MPD did not respond to The Intercept’s emailed questions.)

Last year, the transparency collective known as Distributed Denial of Secrets published 250 gigabytes of MPD emails and attachments, stolen as part of a hack by the ransomware group known as Babuk and made searchable by the Chicago-based Lucy Parsons Labs. Using the documents, news outlets — including The Intercept — revealed that the MPD’s database of supposed gang members is riddled with errors and used to justify aggressive policing of Black communities; that an MPD robbery unit likely engaged in “jumpout” intimidation tactics and targeted schools and youth; and that a powerful MPD tribunal overrides the department’s attempts to fire bad cops. Unreported emails in the trove shed light on the D.C.-area law enforcement agency’s elaborate surveillance operation.

And this week, a band of civil rights organizations known as the ICE Out of DC Coalition published a report — based on documents obtained through public records requests as well as public sources — mapping out many of the capital region’s law enforcement surveillance agencies and technologies.

Taken together, the report and the hacked documents provide a first-of-its-kind look into the close and frequently invasive eye the police keep on D.C.-area residents.

“Many of these systems are constantly collecting information about D.C. residents and can provide precise details on their daily lives in real time,” said Dinesh McCoy, a staff attorney at Just Futures Law and co-writer of the ICE Out of DC report. He pointed to the cops’ practice of sifting through social media, calling it “troubling,” especially when targeting First Amendment-protected activities.

“There’s a real potential for this kind of surveillance to cause a chilling effect and a climate of fear around the right to protest in the city, especially for Black and brown people that are targeted most often by police.”

Among the tools to which MPD personnel have access in the JOCC is a powerful computer program known as Aware.

In February 2013, analysts with the department’s intelligence branch gushed over an Associated Press article about the New York City Police Department’s then-newly released Domain Awareness System. The system is a highly controversial, Microsoft-developed program that collects data from security cameras, radar sensors, license plate readers, and numerous other sources to create a surveillance map of the five boroughs with real-time alerts and analytics.

“This sounds fantastic and is incredibly interesting,” one MPD analyst wrote in an email. “It’s an incredible system,” another replied, adding that he had seen it in action the week prior and that the MPD was in talks with Microsoft to develop a similar program. The following year, the MPD’s Aware system was up and running. By late 2015, patrol officers, intelligence analysts, and command staff had access to it.

Like the Domain Awareness System, the MPD’s version of the program uses artificial intelligence to compile various police data sources — including 911 call records, incident and offense reports, gunshot detector alerts, and license plate reader data — as well as open-source information, like social media feeds, and live video from closed-circuit cameras throughout Washington.

Aware is also connected to regional and federal law enforcement databases, like the Washington Area Law Enforcement System and the FBI-administered National Crime Information Center, which, among other records, includes warrants issued by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

Aware then displays that data in a multifaceted interface. Among the included widgets is a “threat console” that lists recently reported incidents. A “correlation panel” automatically connects those incidents to other events, locations, and persons of interest. There is a map window, which allows MPD personnel to view event locations in relation to other areas of interest, including supposed gang territories. One of the widgets opens up video panels that allow officers and analysts to view any of the MPD’s camera feeds with the click of a mouse. (It’s unclear whether Aware only incorporates feeds from the district’s roughly 350 MPD-owned surveillance cameras or if it also streams from the thousands of MPD-accessible cameras owned by other agencies.)

In a promotional video posted to YouTube in 2018, Microsoft representatives demonstrated Aware’s surveillance capabilities by walking through a fictional assault-turned-carjacking scenario. Role-playing as a police sergeant, one representative used Aware to discover that the suspect was on the federal terrorist watchlist. He used police records, gun permit records, license plate readers, security cameras, and Twitter alerts to pinpoint the supposed suspect, then sent that information to the FBI. Eventually, the fictional sergeant was able to coordinate units to intercept the carjacker.

With the demo, the Microsoft reps painted a picture in which seemingly everyday incidents like their fictional assault are cause for police alarm — and thus cause for increased surveillance. (Microsoft declined to comment for this story.)

“When you deal with your jurisdiction and today’s global threat, we have to look a little bit deeper,” one of the representatives explained. “What are the informations [sic] we know, and what is it that makes [what is] on face value a normal 911 call maybe have elevated risk?”

To civil liberties advocates, the rationale is cause for concern. “They’re making tremendous leaps in order to justify the surveillance of Black and brown residents,” said Carlos Andino, a fellow at the Washington Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights and Urban Affairs. “The MPD — and the police in general — the more they get away from 9/11, the more they need to justify their constant surveillance.”

Metro Cops’ Partners

As MPD analysts use Aware to surveil the streets of D.C., an alphabet soup of lesser-known law enforcement bodies that coordinate with the department — including nongovernment organizations — keep their own watch.

A nonprofit association of local and regional government leaders known as the Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments supports its own set of mass surveillance systems, including a network of over 50 fixed and mobile automatic license plate readers and a fingerprint identification system, according to the ICE Out of DC report. A 2019 memorandum says the license plate reader system scans over 500,000 plates each day in D.C. alone, sharing the collected data with 24 federal, state, regional, and local law enforcement agencies.

The Council of Governments also facilitates the sharing of law enforcement intelligence methods, the hacked emails show, through police intelligence and technology committees that host summits to discuss the future of gang enforcement, “crime forecasting,” and other topics.

According to Andino, predicting crime is D.C. police’s latest rationale for heavy surveillance. In February, MPD Chief Robert Contee testified to the D.C. Council that the department is taking an “intelligence-led policing approach” that involves keeping a close watch on certain areas of the district. And Contee has asked for funding for more intelligence analysts and equipment.

Until 2021, the Council of Governments operated a secret face-recognition tech system, data from which it shared with 14 local and federal agencies. It shut down that project after it was revealed that the U.S. Park Police had used it to identify people participating in the 2020 protest at Lafayette Square at which cops tear-gassed demonstrators before then-President Donald Trump staged a photo with a Bible. According to the Washington Post, the face-recognition system, which contained a database of 1.4 million people, was used more than 12,000 times in 2019 and 2020.

Though it’s not an official government organization, the Council of Governments receives millions of dollars a year — nearly $10 million as of 2020 — from local and federal government agencies, including D.C.’s Homeland Security Emergency Management Agency. HSEMA itself operates a system of at least 5,600 closed-circuit security cameras in D.C. and has access to roughly 150 traffic feeds operated by the D.C. Department of Transportation — dwarfing the MPD’s camera system. HSEMA is funded largely through Department of Homeland Security grants, and its operating budget ballooned in recent years — from $70 million in fiscal year 2018 to $320 million in 2021.

HSEMA also operates the D.C. area’s main fusion center, one of the secretive intelligence-sharing hubs created during the post-September 11 expansion of domestic surveillance. The fusion center liaises with no fewer than 25 local, regional, and federal agencies, including the Department of Homeland Security (with which it shares office space), the D.C. Metro Transit Police Department, and the U.S. Park Police.

Since fusion centers are opaque, it’s impossible to know exactly what surveillance data the D.C. fusion center — formerly the Washington Regional Threat Assessment Center, now known as the National Capital Region Threat Intelligence Consortium — disseminates and to which partner agencies. The ICE Out of DC coalition is especially concerned about the information being used for immigration enforcement: D.C. passed “sanctuary city” legislation in 2020 that prohibited district agencies from collaborating with and sharing certain information with ICE, but with the Department of Homeland Security — ICE’s parent agency — so deeply enmeshed in this web of surveillance tech and tactics, there are unanswered questions about the coordination between the feds and local cops. (For example, through a data-sharing program, Homeland Security, HSEMA, the fusion center, and the MPD — among other agencies — are able to exchange classified information.)

“D.C. has so many overlapping local and federal law enforcement entities and surveillance systems,” said McCoy, of Just Futures Law. “And that ecosystem creates many potential avenues for either direct or inadvertent cooperation between local police and ICE.”

Discontent

Whatever the extent of its cooperation with ICE, HSEMA and its fusion center work extensively with the MPD. Among other information, the hacked emails show that the MPD’s intelligence branch shares data from and access to its parolee GPS tracking software, known as VeriTracks, and lists of people on its gang database with HSEMA and fusion center personnel.

The agencies are close partners in surveillance — although the emails suggest that the relationship isn’t always friendly. In 2012, fusion centers came under fire after a Senate investigation castigated them for wasteful spending, ineptitude, and civil liberties intrusions. The morning of the report’s public release, MPD intelligence analysts shared a Washington Post article about it among themselves.

“The issues they describe in the article are the exact issues I see with my experience with the fusion center,” one analyst wrote, accusing fusion center personnel of getting paid “six figures” to “sit in a room and watch the news indefinitely.”

“All of them make 100k plus,” another analyst replied. “They put out bulletins that are of no interest to law enforcement OR their federal partners. They refuse to learn anything new or analytic techniques even when its free and offered (by me). They covet data … but then lack the ability to do anything with it.”

He wrote, “I wouldn’t come to their defense at all.”

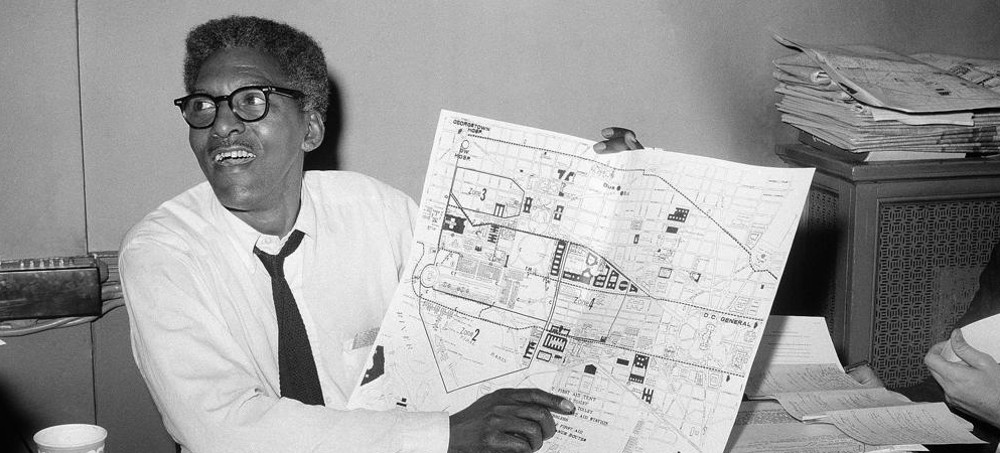

Bayard Rustin, deputy director of the planned march on Washington program, points to a map showing the line of march for the demonstration for civil rights during a news conference in New York on Aug. 24, 1963. (photo: AP)

Bayard Rustin, deputy director of the planned march on Washington program, points to a map showing the line of march for the demonstration for civil rights during a news conference in New York on Aug. 24, 1963. (photo: AP)

“We failed these men,” said Superior Court Judge Allen Baddour, who presided over the special session and at one point paused to gather himself after becoming emotional.

“We failed their cause and we failed to deliver justice in our community,” Baddour said. “And for that, I apologize. So we’re doing this today to right a wrong, in public, and on the record.”

Speaking to about 100 people in the gallery, Baddour noted they were gathered in the same second-story courtroom in the historic courthouse where the men were initially sentenced.

On April 9, 1947, a group of eight white men and eight Black men began the first “freedom ride” to challenge laws that mandated segregation on buses in defiance of the 1946 U.S. Supreme Court Morgan v. Virginia ruling declaring segregation on interstate travel unconstitutional.

The men boarded buses in Washington, D.C., setting out on a two-week route that included stops in Durham, Chapel Hill and Greensboro, North Carolina. As the riders attempted to board the bus in Chapel Hill, several of them were removed by force and attacked by a group of angry cab drivers. Four of the so-called Freedom Riders — Andrew Johnson, James Felmet, Bayard Rustin, and Igal Roodenko — were arrested and charged with disorderly conduct for refusing to move from the front of the bus.

After a trial in Orange County, the four men were convicted and sentenced to serve on a chain gang. Rustin later published writings about being imprisoned and subjected to hard labor for taking part in the first freedom ride, which was also known as the Journey of Reconciliation.

Renee Price, chair of the Orange County Board of Commissioners, told the audience that the special session resulted from research by Baddour and his staff that was launched after a previous anniversary of the case.

“We are here, 75 years later, to address an injustice and henceforth to correct the narrative regarding the Journey of Reconciliation and that segment of American history,” Price said.

In 1942, five years before the Chapel Hill episode, Rustin was beaten by police officers in Nashville, Tennessee, and taken to jail after refusing to move to the back of a bus he had ridden from Louisville, Kentucky, author Raymond Arsenault wrote in the book “Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice.” A pioneer of the civil rights movement, Rustin was an adviser to the late Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and was instrumental in organizing the March on Washington in 1963.

Dr. Adriane Lentz-Smith, an associate professor and associate chair in the department of history at Duke University, described Rustin as “a shepherd and a shaper of the 1960s movement.” But Lentz-Smith said his role in the struggle eventually diminished over concerns that his being gay and a former member of the Communist Party could hurt the movement.

“He was deliberately moved out of the spotlight,” Lentz-Smith said. “The very things that make him remarkable and admirable to us ... in 2022 made him profoundly vulnerable” then, she said.

Rustin’s partner, Walter Naegle, spoke by Zoom Friday and said Rustin and the three men “weren’t fighting for their own good will, but for all of us ... Their faith and their consciences compelled them to act.”

Amy Zowniriw, Roodenko’s niece, told the courtroom that her uncle was “the epitome of a moral and righteous citizen, yet he was put in jail for sitting next to his dear friend, Bayard Rustin.”

Last month, five District Court judges marked the 75th anniversary of the arrests of Rustin and the three other men in Chapel Hill by reading a statement of apology.

“The Orange County Court was on the wrong side of the law in May 1947, and it was on the wrong side of history,” the statement read. “Today, we stand before our community on behalf of all five District Court Judges for Orange and Chatham Counties and accept the responsibility entrusted to us to do our part to eliminate racial disparities in our justice system.”

Environmental groups are arguing the Biden administration hasn't considered the damage that climate-changing carbon dioxide emissions from drilling does to endangered species. (photo: Getty)

Environmental groups are arguing the Biden administration hasn't considered the damage that climate-changing carbon dioxide emissions from drilling does to endangered species. (photo: Getty)

The groups argued the administration hasn’t considered the damage that climate-changing carbon dioxide emissions from drilling does to endangered species, and that permit approvals in Wyoming and New Mexico violated federal laws including the Endangered Species Act.

The groups said burning fossil fuels from drilling is heating the planet and damaging imperiled species like Hawaiian songbirds, desert fish, ice seals and polar bears. The administration’s approved permits, they said, will release up to 600 million metric tons of greenhouse gas emissions.

The lawsuit is the latest attempt by environmentalists to pressure the administration to halt new drilling permits. Earlier in his term, Biden sought to commit to his campaign promise to suspend new drilling on federal lands, but was thwarted after legal challenges from GOP-led states and the oil industry.

“Fossil fuels are driving the extinction crisis, and the Bureau of Land Management is making things worse by failing to protect these imperiled species,” Brett Hartl, government affairs director at the Center for Biological Diversity, said in a statement.

The Center for Biological Diversity, WildEarth Guardians and the Western Environmental Law Center filed the lawsuit against the Bureau of Land Management in the District Court of Washington, D.C., on Wednesday.

An Interior Department spokesman declined to comment on the litigation.

As U.S. energy prices soar, the Biden administration has encouraged companies to increase drilling, arguing they can produce more by using some of the 9,000 unused and available permits. This month, the administration is set auction off drilling leases in states including Colorado, Montana, New Mexico, Nevada, North Dakota, Utah and Wyoming.

Oil and gas industry representatives said that multiple rounds of environmental analysis are conducted before an oil and gas permit on public land is issued, and that environmental groups have several opportunities to file suit during various stages of planning.

Kathleen Sgamma, president of the Western Energy Alliance, a trade group that represents the oil and gas industry, said the climate groups “will not be satisfied until federal oil and natural gas is shut down completely, yet that option is not supported by law.”

“They’re trying to use the courts to deny Americans energy and drive up prices because they can’t convince Congress to change the law,” Sgamma said in a statement. “Shutting down federal oil and natural gas does nothing to address climate change, but merely shifts the production to private lands or overseas.”

The groups argued that the Bureau of Land Management violated the National Environmental Policy Act by failing to consider how approving the permits would impact the environment. They also said officials failed to stop “unnecessary and undue” damage to federal lands as required by the Federal Land Policy and Management Act.

“The Bureau of Land Management has admitted that continued oil and gas exploitation is a significant cause of the climate crisis, yet the agency continues to recklessly issue thousands of new oil and gas drilling permits,” said Kyle Tisdel, climate and energy program director with the Western Environmental Law Center.

IT'S TIME TO REDUCE OUR CONSUMPTION!

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.