Dear Friend,

Chris Smaje argues that we need to talk openly and calmly about the possibility of societal or civilizational collapse arising from humanity’s present predicaments – not so much what the likelihood or the underlying mechanisms of collapse might be, but the idea that it would be useful if, as a society, we could talk about it.

Kindly support honest journalism to survive. https://countercurrents.org/subscription/

If you think the contents of this news letter are critical for the dignified living and survival of humanity and other species on earth, please forward it to your friends and spread the word. It's time for humanity to come together as one family! You can subscribe to our news letter here http://www.countercurrents.org/news-letter/.

In Solidarity

Binu Mathew

Editor

Countercurrents.org

Business-as-usual porn – or, We need to talk about collapse

by Chris Smaje

I think we need to talk openly and calmly about the possibility of societal or civilizational collapse arising from humanity’s present predicaments. And that’s mostly what I want to pursue in this post – not so much what the likelihood or the underlying mechanisms of collapse might be, but the idea that it would be useful if, as a society, we could talk about it.

I think we need to talk openly and calmly about the possibility of societal or civilizational collapse arising from humanity’s present predicaments. And that’s mostly what I want to pursue in this post – not so much what the likelihood or the underlying mechanisms of collapse might be, but the idea that it would be useful if, as a society, we could talk about it.

Maybe that’s happening in one sense. The noises offstage from scientists, multilateral agencies, social critics and political activists about the possibility of collapse are getting louder1. Inevitably, so is the pushback from those arguing that this is so much overheated rhetoric, and everything’s just fine2. My sense is that there’s far greater empirical weight behind the former than the latter position, but it’s the latter one that seems to dominate public discourse. There’s precious little public and media attention to the rather big news that the way we live may soon be ending. Indeed, people who say such things are generally relegated from serious debate, and sometimes accused of peddling ‘collapse porn’ with their mawkish tales of impending doom3. It’s a curious phrase. Inasmuch as pornography presents people with something that they guiltily want to see, but in unrealistic and idealized ways that hide the reality of the relationships involved and erode their integrity, perhaps we should rather be talking about ‘business as usual porn’.

I’m not too sure why business as usual porn is so widespread, but I think possibly it’s because of an unfortunate fusion between two aspects of modern life. First, a sense that the vast technological reach of contemporary societies armours us against the malign contingencies of the world, and second an elaborate and urbanized division of labour that denies most people even the remotest capacity to care for themselves in the face of those contingencies. The result at best is a cheerful fatalism – “there’s nothing I can do about it, so I might as well enjoy myself” – and at worst a kind of Stockholm syndrome in which we celebrate our armoured urbanism, latch onto every sign of its vitality and dismiss any counternarrative out of hand.

In his lovely book about foraging and hunting peoples, Hugh Brody describes a very different situation among the Inuit hunters with whom he lived4. Every journey across the ice was rimed with potential danger, which was freely acknowledged. The Inuit were well aware of the malign contingencies of the world over which they had little ultimate control – a situation that made them neither fearful, nor selfish, nor angry, nor sad, but in some sense alive within a culture that had to deal with it. And they had many skills for dealing with what came their way, as hunters, builders, navigators, craftspeople and so on. My sense is that they didn’t spend much time debating whether they were optimistic or pessimistic about their uncertain future, nor in honouring leaders who cheekily mocked ‘project fear’ and lambasted ‘doomsters and gloomsters’. Instead, they carefully assessed the dangers ahead that they perceived, prepared themselves as best they could to mitigate them, but were open to the inscrutable workings of uncontrollable contingency.

My feeling is that we could do with channelling a bit of that mentality in our now-challenged world. Perhaps one of the differences between our predicaments today and those of the Inuit is that our problems are fundamentally collective. Often, in non-modern foraging or farming societies centralization and bureaucratization has been a risk-pooling venture by people with other options up their sleeve (I’m borrowing here from archaeologist of premodern societal collapse, Joseph Tainter5). When the going gets rough for the state superstructure, people readily abandon it and pursue a more dispersed and self-reliant life – perhaps something akin to the kind of life lived by the Inuit hunters described by Brody. One of the problems we face today is that, for most of us, it’s not so easy to walk away and lead a more self-reliant life. We lack the space, the skills and the political warrant to do so. These are all genuinely difficult problems, but perhaps as big a problem is that we also lack the cultural language to do so. We’ve become so wedded to urbanism, economic growth, high tech (or, in fact, high energy) solutionism and narratives of historical progress that a turn to self-reliance seems undesirable, impossible, laughable – what someone I was debating with recently called a ‘neopeasant fantasy’.

I guess I’ll continue that debate, wearily. It seems to be a thing I do. And I haven’t given up on it entirely – if I can help break down the resistance to an alternative cultural narrative in a few minds, then I guess that’s something. But I want to imagine myself metaphorically out on the ice with Inuit hunters as Hugh Brody was, with no food, no game in evidence, and many days journey from safety, with only a tired dog team, my knowledge of the terrain, my hunting skills and my fortitude in my favour.

Of course, in reality I’m not out on the ice but on a small farm near the edge of a small town in a small country that’s thoroughly imbued with the culture of global capitalism. I can try to imagine a cultural awakening fit for my time and place, but to write it down on the page will make it thinner and more fugitive than it needs to be in practice. The words I’d write on the page would probably include things like autonomy, self-reliance, community, land, skill, care, craft, work, health, nature, play, creation, love and argument. You can write those words for most cultures. But I think they’ll soon mean different things in our culture than they do now. The trick is going to be building out quickly from the place where we now are, creating culture in practice, but letting go of a lot that we now take for granted, or insist upon. We need to build a new culture that’s calmly open and alive to the possibilities and dangers of the present and the journey ahead, not angrily insistent upon the virtues of the path that took us to where we now stand.

So I don’t think it’s worth spending too much time debating on paper (or online) the detailed shape and content of that new culture. I think it’s better to shape it in practice, by doing what we can as peacemakers, storytellers, educators, healers or agents of the practical arts to breathe local life into it. But I do think it’s worth spending time debating the political and historical circumstances in which that shaping can take off and propagate. And that’s why the inability to countenance collapse in mainstream discussion, our obsession with business as usual porn, is frustrating. Because we need to talk about collapse. I’m not saying that everybody needs to agree it’s inevitably going to happen. But I think it would be good if there was wider acceptance in mainstream discussions that, on the basis of the evidence before us, it’s a reasonable possibility to reckon with. In fact, if our culture were able to countenance this and take it in its stride, I’d probably downgrade my estimation of its likelihood.

I’d liken my position to a tourist on a river rowboat, supping at the bar and enjoying the scenery as we float along. There’s a distant roar, and on the horizon I see a smudge of spray. The current has started running faster and grown sinuous. Coming up quickly on the far bank there’s a placid creek.

“Gosh, seems like there’s quite a waterfall ahead,” I say to my fellow passengers.

One of them cups her ear.

“Nah, can’t hear anything,” she says.

“I really don’t think so,” another replies, “The captain wouldn’t put us into that kind of peril.”

“Don’t be such a killjoy,” says a third. “Carpe diem is my motto. I’m enjoying my drink. We all die in the end anyway.”

“We’ll be fine,” says another. “Somebody’s soon going to figure out how to make some wings and fit them to the boat. If there’s a waterfall, we’ll just fly over it.”

“All the same”, I say, “if we all get down onto the deck quickly and help the oarsmen we might just be able to row into that creek – then we’re sure to be in safer waters.”

“Are you serious?” says another passenger. “I didn’t pay for this holiday just to go back to doing a load of backbreaking work.”

But, privately unsettled by my words, the passengers seek reassurance. “Don’t worry. I know his sort of alarmist very well”, says Captain Shellenberger, nodding in my direction, “and I’d like to apologise on his behalf. Just look how beautiful the river is right here. And it’s even better up ahead. Now, who wants another drink?”

I’m not really down with Ted Kaczynski’s ship of fools, but despite the captain’s words I’m pretty sure we’re in for a rude awakening. Unfortunately, with everyone on board so deeply into their business as usual porn there’s not much I can do about it. And what I don’t know as the curtain of spray approaches is whether we’re just going to bump down and lurch uncomfortably around in the rapids for a while, or whether we’re going to fly over a precipice and be dashed on the rocks hundreds of feet below.

A reviewer of John Michael Greer’s latest offering writes that many people today succumb to an “odd fallacy” that collapse will be fast, when we know from past social collapses that they’re usually slow. In this view, intimations of fast collapse are another version of business as usual porn, because they suggest there’s nothing to be done. We’re screwed – might as well just have another drink.

I understand the concept of slow collapse. Charlemagne was crowned emperor of Rome in 800AD, long after anything that truly resembled the Roman empire had ceased to exist, and Byzantines were still calling themselves ‘Romans’ around that time. I daresay people might still be calling themselves ‘American’ or ‘English’ in centuries hence. But Charlemagne and the Byzantines didn’t have to contend with rapid global temperature and sea level rises whose expected upper bounds are at the kind of levels we know caused mass extinctions in the geological past – slow extinctions no doubt, as measured by human years, but also not ones enmeshed in the fragile interdependencies of complex civilization. Even then, it’s worth considering what collapse might look like as it happens – not necessarily a Mad Max world of anarchic violence, maybe a slow unravelling of political order and economic wellbeing of the kind that already seems underway. And even if future climate disruptions prove only modest, there are numerous other political, economic and biophysical crises looming that suggest change to business as usual is imminent, however much the status quo gratifies some of us.

When I wrote something similar a few years back, one of the captain’s crew responded along the lines that “you can almost hear Smaje wringing his hands with his fears about the future”. But I’m not frightened. We need to jettison these dualities of optimism and pessimism, hope and fear. Optimism to hang onto a world where half the population live in rank poverty? No thanks. I think we need to cultivate something of the insouciance about a rapid change of circumstances of the Inuit, or of those premodern citizenries described by Tainter, who shrugged and walked away.

So where I think I need to be is out on the ice, my belly empty and my eyes open, attentive for prey. By that I don’t mean that personally I’m fully prepped up for the contingencies of a Mad Max world, nor that my hands are unsullied by any traffic with the capitalist present. I mean that I want to be outside the tent, surveying the terrain, not inside it telling tall tales about the rich hunting grounds we’re sure to find just as soon as we step outside.

To return to my other metaphor, I think there’s a good chance that when the boat slips over the edge, it’s going to be worse than just bumpy. To me, that’s not an inducement to have another drink, but one to quit the bar, get down on the deck and start rowing. To do that, though, we first need to kick the porn habit and start talking, properly, about collapse.

References

- E.g. https://voiceofaction.org/collapse-of-civilisation-is-the-most-likely-outcome-top-climate-scientists/; https://www.vice.com/en_uk/article/8xwygg/the-collapse-of-civilisation-may-have-already-begun; https://gar.undrr.org/sites/default/files/chapter/2019-06/chapter_2.pdf; http://lifeworth.com/deepadaptation.pdf; This Is Not A Drill: An Extinction Rebellion Handbook, Penguin, 2019; David Wallace-Wells The Uninhabitable Earth, Penguin, 2019.

- E.g. Michael Shellenberger Apocalypse Never, Harper 2020.

- E.g. Leigh Phillips Austerity Ecology and the Collapse Porn Addicts, Zero, 2015.

- Hugh Brody The Other Side of Eden: Hunters, Farmers and the Shaping of the World. North Point, 2000.

- Joseph Tainter. The Collapse of Complex Societies, Cambridge University Press, 1988.

Chris Smaje works a small mixed farm in Somerset and blogs at smallfarmfuture.org.uk. He’s written on environmental and agricultural issues for publications like The Land, Permaculture Magazine and in Dark Mountain: Issue 6, and also in academic journals (Agroecology & Sustainable Food Systems; the Journal of Consumer Culture; the Journal for the Study of Religion, Nature and Culture). Trained in anthropology and social science, he previously worked at the Universities of Surrey and London.

Originally published in Small Farm Future

John Lewis: The Iconic Civil Rights Leader Dies

by Zeenat Khan

This is a sad day for America. John Lewis, US Congressman and key leader of civil rights movement died in Atlanta, Georgia, last night. He was diagnosed with stage 4 pancreatic cancer in 2019. Lewis was 80 years old.

FILE – In this Feb. 15, 2011, file photo, President Barack Obama presents a 2010 Presidential Medal of Freedom to U.S. Rep. John Lewis, D-Ga., during a ceremony in the East Room of the White House in Washington. Lewis, who carried the struggle against racial discrimination from Southern battlegrounds of the 1960s to the halls of Congress, died Friday, July 17, 2020. (AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster, File)

This is a sad day for America. John Lewis, US Congressman and key leader of civil rights movement died in Atlanta, Georgia, last night. He was diagnosed with stage 4 pancreatic cancer in 2019. Lewis was 80 years old. “Today, America mourns the loss of one of the greatest heroes of American history: Congressman John Lewis, the Conscience of the Congress, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi said late Friday.” The lasting image of John Lewis that is embedded in my memory: March 7, 2015, when John Lewis went to Selma, Alabama with President and Mrs. Barack Obama to observe the 50th anniversary of the “Bloody Sunday” March which changed American history. On that historic day thousands had gathered on the Edmund Pettus Bridge to listen to President Obama and Congressman John Lewis. It was the same bridge where John Lewis stood with Martin Luther King, Jr. five decades ago. Before starting his speech, Obama introduced Lewis as one of his heroes. As an acknowledgement to his struggle for racial justice, and for his non-violence approach during the civil rights movement, Obama had adorned him with the Medal of Freedom. This highest civilian honor was given to him on the eve of the Freedom Riders 50th anniversary. “Generations from now,” Obama said when awarding him a Medal of Freedom in 2011, “when parents teach their children what is meant by courage, the story of John Lewis will come to mind — an American who knew that change could not wait for some other person or some other time; whose life is a lesson in the fierce urgency of now.”

Congressman Lewis had earned the nickname the “old lion” because he carried himself with the “royal bearing of one.” John Lewis played a very important role during the civil rights movement – he became a symbol of non-violence about the way he fought for the basic rights of the African Americans that was promised to them when slavery was abolished. Lewis had worked closely with Martin Luther King, Jr. during the time of the civil rights movement. Under King’s direction Lewis and another activist named Hosea Williams led the mighty “Selma March” which procured voting rights for the African Americans.

During the March when hundreds of African Americans followed Lewis, the demonstrators and some of the activists were beaten with Billy clubs and bloodied by state troopers as they approached the bridge. Police released tear gas as the marchers crossed the county line. Undeterred, they continued on the 54-mile trek towards state capital Montgomery. They were set on their mission to demand for new legislation to be signed by President Lyndon B. Johnson so that they can exercise their right to vote. The marchers had decided to take their complaint directly to the Alabama governor George Wallace who was a segregationist. Prior to the march he had issued an order for all the white people to stay home and not to participate or show solidarity with the marchers. Thousands came out despite his warning and stood watch waving the confederate flag. Wallace refused to protect the marchers and instead dispatched state troopers to handle them.

Even before the Selma to Montgomery March, John Lewis’s momentous contribution to the civil rights movement is humongous and usually is highly revered by all Americans. Lewis, a son of a sharecropper, was a theology student in Alabama. At the time he was twenty-one years old. He was one of the original groups of 13 riders (seven black, six white) of the Freedom Riders who were fighting racial segregation in the Deep South. The activists rode a bus from Washington DC that headed south to test a Supreme Court decision. A year ago, in 1960, the SC invalidated the segregation of the interstate transportation, and the facilities at the bus and train terminals. The bus ride was supposed to prove whether the integration in the reluctant and heavily segregated South was actually implemented.

The bus riders took on the entire system built on hating their black skin. The riders knew it could end up badly. They risked everything to take a ride for freedom. They left on May 9, (Mother’s day), in an effort to end segregation in the United States. In Rock Hill, North Carolina, at the bus depot, Lewis and his white friend were badly beaten and bloodied. Elwin Wilson was one of the perpetrators who had attacked Lewis. Young Lewis was determined to reach his destination, and they continued on.

Later one of the Freedom Riders bus was first stoned, the students beaten, and was firebombed as it approached Anniston, Alabama. The passengers escaped only to face vicious mobs, the heinous members of the KKK and jail cells. There were a total of 436 people who were on different buses, which came from different strategic points across the country with the same goal. In their struggle against racism and injustice, they helped the US to change laws where everyone in this country can use the same public amenities while they are travelling.

In 2011, on the 50th anniversary of the Freedom Ride Lewis had given many interviews and had recalled his experience. He stated, “Boarding that Greyhound bus to travel through the heart of the Deep South, I felt good. I felt happy. I felt liberated; I was like a soldier in a nonviolent army.” This movement was greatly influenced by Mahatma Gandhi’s nonviolent teachings and philosophy. What the Freedom Riders demonstrated in 1961 hastened the United States in taking a bigger step towards desegregation which ignited a nationwide movement for civil rights.

Lewis’s philosophy resonates with this quote: “To err is human, to forgive divine.” Forgiveness in the Biblical sense perhaps is a hard thing to do. In May 2011, in the spirit of true forgiveness, John Lewis did just that. On national television, he publicly forgave his abuser, Elwin Wilson who beat him up at the bus depot in North Carolina. In 1961, Wilson, a member of Ku Klux Klan (KKK), beat the life out of Lewis, because of the color of his skin. When John Lewis got a chance to confront his abuser half a century later, he showed no desire to avenge the burning pain and perhaps rage he must have felt from time to time about the fateful day. In its place John Lewis showed humility, and his human capacity to forgive.

On TV, Lewis had held Wilson’s hand and told him, “Love is much stronger than hate,” and he forgives him. It was a true moment of reconciliation. It would have been perfectly justified if Lewis had refused to sit next to Wilson, let alone accept his apology, after the way he degraded him. By demonstrating a benevolent sympathy and by showing his ability to forgive a person who had done him wrong is a testament to courage, moral decency, and generosity of his spirit. In a candid conversation he let Wilson know that he understands what motivated him because they both were victims of segregation. In his own words why he forgave his abuser: “If we are to emerge unscarred by hate, we must learn to understand and forgive those who have been most hostile and violent towards us.”

The in-person apology on Wilson’s part did open up a “grand canopy of human togetherness” — out of hate grew tenderness.

Fifty years later, it showed that early on John Lewis made a decision to move on with his life, without being bitter and blinded by prejudice and hate. For his own sake he let go of his private pain which had helped him to validate his own worth as a human being. Since then he had dedicated much of his career to public service.

What about Elwin Wilson, the Ex-Klansman? What has his life been like since he horribly beat up Lewis? As a KKK recruit, he took an oath to hate all black people. It gave him no peace and he strived to make amends for what he had done. Throughout his life he had been sorrowful when he realized how inextricably he had been caught up in hate. His need for an apology grew day by day for the violence he had inflicted on Lewis, five decades ago. In 2009, he came to Congressman John Lewis’s Capitol Hill office in Washington DC, to offer him an apology that he has been carrying in his heart. He told Lewis that he thought about him a lot, and felt a longing to seek him out because “Hate is too heavy a burden to carry.” The public apology came on May 4, of the same year.

For some of the Freedom Riders like John Lewis, living a life with the emotions and the experience of that appalling day in 1961, positioned them to be stronger forces and advocates against racism. A lot of them went on to become social workers, preachers, lawyers and public servants. Lewis’s work was still not done until his cancer diagnosis came. He was serving his fourteenth consecutive term in the Congress.

John Lewis felt the scars of racism were deeply rooted in the American consciousness. Though the country has come some distance in getting rid of xenophobia, but there is still a lot of hate that lingers. The recent police brutality across America has opened old wounds of racism and the demonstrations have sparked unrest.

Until recently, many African American youth did not feel much “emotional connection” to the civil rights movement for equality or about the struggles from what they read in social studies class. When I had taught Middle School, I saw that the school curriculums shelter the students from the shameful history of segregation. The students had no understanding of what their predecessors went through in the 60s, to force integration in the South. In January 2015, a film called Selma was released for the young generation of Americans to learn a pivotal lesson as to what had happened in Selma, Alabama.

Rep Lewis, one of the most courageous and towering figure of the civil rights movement had played many key roles including organizing the 1963 March on Washington. He dedicated his life to protecting human rights and also focused in advocating equality for all minorities, and had made immigration a new civil rights battle in the last decade.

Rep. John Lewis marches to the headquarters of U.S. Customs and Border Protection to protest the Trump administration’s family separation policies on June 13, 2018 in Washington, DC. | Alex Wong/Getty Images

John Lewis had tried hard to keep the movement of equal rights alive by sensitizing all the young American people about present day-racism. In a world of difference, he had urged them to take on a different kind of bus ride in fighting prejudice, and hate crimes. He advocated having respect for diversity.

What was most astounding about Congressman Lewis is his capability to reconcile with a life changing episode. He rose above the dreadful experience while riding the bus. His resilience showed that he saw a bigger need to educate and change the customs and the laws of the land. To resolve the issue of race and for the Americans to have an understanding of the dark past of division and separation bypassed his need for seething in anger.

As a Freedom Rider, the youngest of the Big Six civil rights activists, and a visionary, John Lewis had made it his life’s mission to take back Americans to the roots of the civil rights movement. He and the other riders braved unimaginable disgrace in their struggle against racism for the future generations to live a life of equality that was envisioned by Martin Luther King, Jr. If Lewis and others didn’t dare to take those buses for freedom, then perhaps there will still be segregation in America.

With John Lewis’s death, America has lost one of its most important voices. The latest police brutality in Minneapolis and Atlanta had resulted in the deaths of two black men, George Floyd and Rayshard Brooks. The global and Black Lives Matter protests reaffirm and reveal that white supremacy is a problem everywhere. America can’t act like a team and it is feuding and facing chaos because of pandemic, recession and unrest. Many unresolved race relations issues, and the division between black, white, and everyone in-between are more evident now than ever before in recent years. During these confusing times the Americans can take a moment and reflect on the courage that John Lewis and Elwin Wilson had demonstrated. They must remember that every human being has a voice, and he/she can be a champion for change. Without feuding, hating one another people everywhere should have a look at Lewis’ life and believe in the power of redemption. Everyone must work harder to resolve the race disputes to improve race relations. We must not forget how the reunion between Lewis and Wilson had restored one’s faith in the power of grace, humility and love. With the Freedom Riders, John Lewis stood up to the injustices and prejudices, in a peaceful, nonviolent, Gandhian way.

May John Lewis rest in peace!

Zeenat Khan writes from Maryland, USA

The Bomb

by Bhaskar Parichha

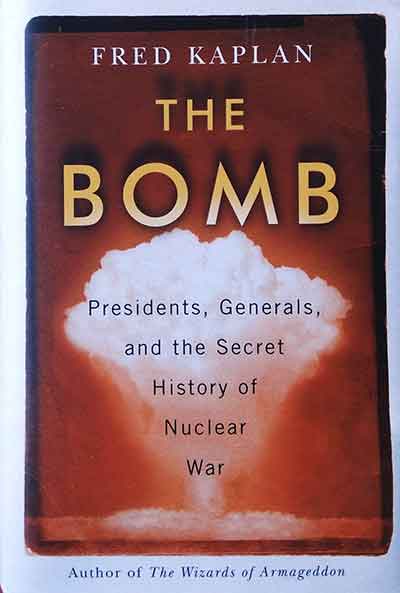

In the present book ‘The Bomb: Presidents, Generals, and the Secret History

of Nuclear War’, Kaplan has come up with the story of the Bomb from the dawn of the atomic age until today. Based on exclusive interviews and previously classified documents, this is a historical research and can safely be categorized as deep reporting.

When a defense researcher and an aggressive reporter takes us into the White House Situation Room, the Joint Chiefs of Staff’s “Tank” in the Pentagon, and the gigantic chambers of Strategic Command to bring the myriad stories of how America’s presidents and generals have thought about, threatened, broached, and just about avoided nuclear war, it is bound to be an exceptional book.

Fred Kaplan is the national-security columnist for Slate and the author of five previous books, Dark Territory: The Secret History of Cyber War, The Insurgents: David Petraeus and the Plot to Change the American Way of War (a Pulitzer Prize finalist and New York Times bestseller), 1959, Daydream Believers, and The Wizards of Armageddon.

In the present book ‘The Bomb: Presidents, Generals, and the Secret History of Nuclear War’, Kaplan has come up with the story of the Bomb from the dawn of the atomic age until today. Based on exclusive interviews and previously classified documents, this is a historical research and can safely be categorized as deep reporting.

Dr. Kaplan has discussed at length theories that have dominated nightmare scenarios from Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Then he presents the unthinkable – in terms of mass destruction. He also demonstrates how the reality of a nuclear war will not go away, regardless of the calamitous consequences.

Examine these lines: ‘in public, over the years, officers and officials have described America’s nuclear policy as second-strike deterrence: if an enemy strikes us with nuclear weapons, we will retaliate in kind; this retaliatory power is what deters the enemy from attacking us.’

‘In reality, though, American policy has always been to strike first preemptively, or in response to a conventional invasion of allied territory, or to a biological or large-scale cyber attack: in any case, not just as an answer to a nuclear attack. All of these options envision firing nuclear weapons at military targets for military ends; they envision the bomb as a weapon of war, writ large.’

Furthermore, ‘this vision has been enshrined in the American military’s doctrines, drills, and exercises from the onset of the nuclear era through all its phases. Most presidents have been skeptical of this vision—morally, strategically, practically—but none of them have rejected it. Some have threatened to launch nuclear weapons first as a way of settling a crisis. The few who considered adopting a “no first use” policy, in the end, decided against it.’

The book is an impressive account of the various permutations of the official nuclear bomb policy of the United States. Organized into individual chapters devoted to every president – the sections take us to a coherent end.

With hindsight, if the end of the Cold War has given the incumbent president more control over the policy, Kaplan’s book says it all in splendid details: ‘For thirty years after the Cold War ended, almost no one thought, much less worried, about nuclear war. Now almost everyone is fearful. But the fear takes the form of a vaguely paralyzed anxiety. Because of the long reprieve from the bomb’s shadow, few people know how to grasp its dimensions; they’ve forgotten, if they ever knew.’

In the chapter on the present US President Kaplan is guileless: ‘The holiday from history ended on August 8, 2017, when President Donald Trump, barely six months in office, told reporters at his golf resort in Bedminster, New Jersey, that if the North Koreans kept threatening the United States with harsh rhetoric and missile tests, “they will be met with fire and fury like the world has never seen.”

Elsewhere he notes: ‘then, six months later, Trump signed and released his administration’s Nuclear Posture Review, a seventy-four-page document that called for building new types of nuclear weapons and integrating them with the military’s conventional war plans—in short, for treating nuclear weapons as normal. The red lights flashed the alarm bells rang furiously.’

Interestingly, there is a throwback to the times of President Truman and how both he and trump used similar rhetoric: ‘Even to those who didn’t remember President Harry Truman’s similar description, seventy-two years earlier, of the atomic bomb that destroyed Hiroshima (“a rain of ruin from the air, the like of which has never been seen on this earth”), it was clear that in language more bellicose than any president’s since the end of World War II, Trump was talking about launching nuclear weapons at North Korea.’

Kaplan writes rather pragmatically: ‘Understanding the nuclear era—the era of our lifetime—means understanding the rabbit hole: who dug it and how we got stuck inside. It means tracing the maze of its tunnels, which is to say, the arc of its history: a story enmeshed in secrecy, some of it still secret, much of it now illuminated—by declassified documents and interviews with key actors—though never fully told. How did we get to this second coming of nuclear panic?’

With reliable anecdotes and a wealth of historical detail, ‘The Bomb’ is like the ‘Pentagon Papers’ for the U.S. nuclear strategy. Kaplan has the ‘insider stories of an investigative journalist, the analytic rigor of a political scientist, and the longer-term perspective of a historian.’

The book is highly comprehensible and will surely make it to the permanent record of global nuclear politics. For war enthusiasts, this 375-page hardback is a must-read.

The Bomb

Fred Kaplan

Simon & Schuster, New York

2020

Bhaskar Parichha is a senior journalist and author based in Bhubaneswar

‘Optimism of the Will’: Palestinian Freedom is Possible Now

by Dr Ramzy Baroud

In his “Prison Notebooks”, anti-fascist intellectual, Antonio Gramsci, coined the term “pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will.” While logical analysis of a situation may lead the intellect to despair, the potential for social and political revolutions and transformations must keep us all motivated to keep the struggle going, no matter the odds.

Appeal to Chhattisgarh CM: Stop Eviction & Demolitions in Workers Bastis, Bhilai Industrial Area

by National Alliance of People’s Movements

Request to stop the eviction of workers in the Bhilai Industrial Area and demolition of their houses in Bijli Nagar

Netflix, Chattichoru and Chumpak……

by G Pridhvi Kanth

As a population with the symptoms of community disintegration, mental distress, and an incessant surge in the social divide and economical inequalities, the global south redeems not just for diagnosis blaming on neoliberals, but a pragmatic cure is quintessential.

Policeman as the mighty hero: How cinema normalises violence by Policemen?

by Sanchit Srivastava

It is high time one questions the eulogization of police brutality by cinema as it justifies custodial deaths and encounters.

The way

homo sapiens stopped living

by Mohit Sharma

A take on the life in COVID times

Minority panel report, faulting police & BJP leaders for Delhi riots, gets a lukewarm media response

by Dr Abhay Kumar

The mainstream media – particularly Hindi newspapers – has downplayed the news about the release of a fact-finding report by Delhi Minorities Commission on February Delhi riots, 2020. Releasing its report on Thursday, the commission has faulted the role of top BJP leaders in giving hateful speeches and inciting the violence. It has also accused the police of inaction and complicity during the riots.

The ‘Appearance’ & ‘Disappearance’ of the Migrant Worker

by Mrinalini Paul

The following account stems from stories that a group of volunteers engaged with the Right to Food & Work Campaign, West Bengal ,encountered while working with migrant labourers from the state stuck in other parts of the country due to the lockdown announced from 24th March 2020 onwards

India Both Internally And Externally Strained

by Haider Abbas

As if the Chabahar debacle was not enough, as Iran scrapped its deal with India and instead entered into a 400 billion USD deal with China, that Iran has also now decided to keep India ‘out’ from Gas Field Right Exploration by saying that India would be involved ‘appropriately’ at some later stage 1. Bad news for India. One thing however is for sure that US would do everything to scuttle the Iran-China deal the same way it has done to spoilsport CPEC.

Female Political Prisoners in West Bengal Jails

by Anonymous

The movement to release political prisoners is gaining steam nationwide. There are 75-76 political prisoners in the various districts of West Bengal. Most of them were associated with the historic mass movements of Nandigram and Lalgarh. There are also some Maoist activists who were directly associated with the party who were caught when they entered the state. All of them have been in custody without trial for many years. It is incumbent on us to demand their release. The following writing was published anonymously in ‘Prisoners Unity’

Hasn’t Hasina’s Gambit Backfired? Isn’t Bangladesh Today a Battlefield of Sino-Indian Proxy War?

by Taj Hashmi

At this moment, nothing can be ruled out, and again, there’s no guarantee of Hasina leaving. China might keep

her in power – albeit for some time – by purging the rabidly pro-Indian elements in the armed forces, law-enforcers, and bureaucracy. A change might be lurking at the end of the tunnel, which is too early to figure out if it would be a protégé of the US-World Bank-UN triumvirate or China and pro-Chinese elements in Bangladesh. Hasina and her party have almost lost Indian patronage, and the discredited generals, RAB, and police officers who were the main agents of rigging the polls (paradoxically with Chinese help) in 2018 are least likely to get any substantial support to manipulate things again to their advantage.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.