Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

Putin’s blackmail is dangerous; its success would be even worse.

About four miles from the runway at Engels where the explosion occurred, a pair of underground bunkers is likely to contain nuclear warheads, with a capacity to store hundreds of them. Blackjacks and Bears were designed during the Cold War for nuclear strikes on NATO countries, and they still play that role in Russian war plans. The drone attack on Engels was a milestone in military history: the world’s first aerial assault on a nuclear base. There was little chance of a nuclear detonation, even from a direct hit on the heavily fortified bunkers. Nevertheless, the presence of nuclear warheads at a base routinely used by Russian bombers for attacks on Ukraine is a reminder of how dangerous this war remains. On December 26, Engels was struck by another Ukrainian drone, which killed three servicemen.

READ MORE  Labour Party leader Jacinda Ardern. (photo: Hannah Peters/Getty)

Labour Party leader Jacinda Ardern. (photo: Hannah Peters/Getty)

Labour leader said that her term would conclude no later than Feb. 7.

Ardern said she “no longer had enough in the tank” to do the job during the party’s annual caucus meeting on Thursday NZ time.

“I’m leaving, because with such a privileged role comes responsibility. The responsibility to know when you are the right person to lead and also when you are not. I know what this job takes. And I know that I no longer have enough in the tank to do it justice. It’s that simple,” she said.

Ardern became the world’s youngest female head of government when she was elected prime minister in 2017 at the age of 37. Her response to New Zealand’s worst mass shooting in history — the 2019 terrorist attack on two Christchurch mosques — gained international attention when she led Parliament in passing significant gun control measures.

During her announcement in the New Zealand city of Napier, Arden said she did not feel equipped to complete another term.

“I believe that leading a country is the most privileged job anyone could ever have, but also one of the more challenging,” Ardern said. “You cannot and should not do it unless you have a full tank plus a bit in reserve for those unexpected challenges.”

“I hope I leave New Zealanders with a belief that you can be kind, but strong, empathetic but decisive, optimistic but focused,” she continued. “And that you can be your own kind of leader – one who knows when it’s time to go.”

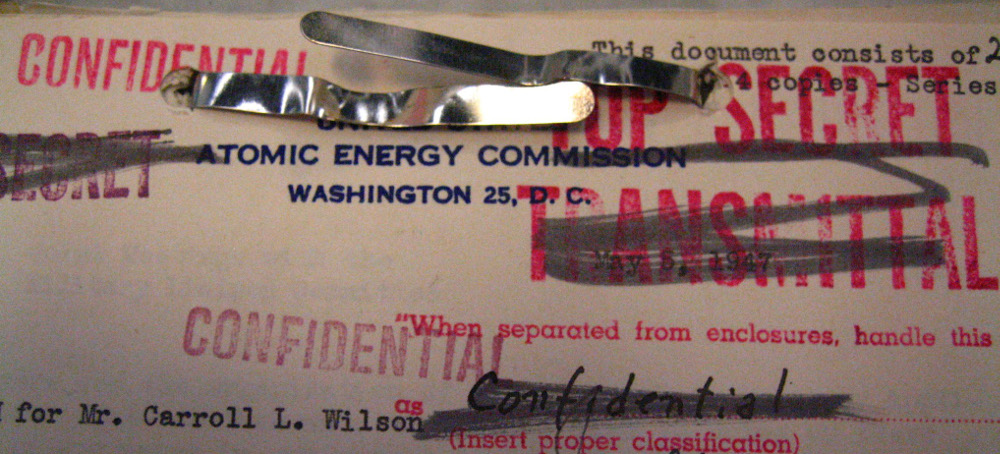

READ MORE  The U.S. government classifies some 50 million documents every year, but doesn't declassify documents at nearly that rate. (photo: Getty)

The U.S. government classifies some 50 million documents every year, but doesn't declassify documents at nearly that rate. (photo: Getty)

First, there was the discovery of hundreds of classified documents inappropriately stored at Donald Trump's Mar-a-Lago estate in Florida. Then, in recent weeks, the discovery of classified documents at President Biden's home and private office.

While these cases are different in scope and circumstance, both demonstrate mishandling of sensitive information – and they have renewed the scrutiny on how the government classifies its documents.

"There's somewhere in the order of over 50 million documents classified every year. We don't know the exact number because even the government can't keep track of it all," Oona Hathaway, a law professor at Yale University and former special counsel at the Pentagon, told NPR.

Hathaway said the rate at which the government classifies documents has created a problem that ultimately makes it harder for the public to hold the government accountable. She spoke with NPR about some of the reasons behind the issue and one of her suggestions to help.

Interview Highlights

On the ways that overclassification of government documents might be a problem

There are a lot of reasons we should care. Probably the first one is that when a document is classified, it means that people in government who have access to that information really can't talk about it. They can't tell the American people what they know. They can't explain it. American people can't see it. And so it makes it very difficult for the American people to know what their government is doing when that information is classified. It also creates all kinds of problems for reporters, because when reporters get access, the information potentially makes them vulnerable to prosecution for violation of the Espionage Act for disclosing classified information. So it creates a lot of problems for democracy and for transparency of our government.

On how overclassification is not a new issue and why it continues to get worse

It's been a problem for decades. People who have been looking at classification and thinking about classification have recognized for a very long time that the system is out of control. And there have been various efforts to try and rein it in over time. President Clinton tried to limit the use of classification and encourage declassification; it didn't really work.

The data that we have is pretty imperfect, but when we look at the data that we can get, presidency after presidency, we see the numbers going up. And that's despite the fact that many presidents have been kind of trying to reign this in. President Obama also tried to make an effort to encourage declassification and he created a center whose job was supposed to be to encourage declassification, and yet the numbers just kept going up.

Part of that is because the incentives for people in government haven't changed. You know, if you're a person sitting at a desk and you're making a decision about whether to classify something or not, there are generally no ramifications if you've classified something that didn't really need to be classified. But if you make it unclassified and it really should have been classified, you potentially could get in a lot of trouble. So for individual people who are making these decisions, they have all the incentive to classify a document and you multiply that over everyone who's in government, and that's part of the reason we end up where we are.

On whether the criticism of overclassification is fair, in Biden's case currently and previously with former President Trump

Well, it's hard to know exactly what's happening with the Biden administration because we haven't seen those documents. And so it's hard to know if those are documents that really should not have been classified. The fact that they're mixed in with a lot of documents that were not classified is suggestive that they were just part of a set of files where classified information kind of got snuck in and they inadvertently took the boxes with them when they left. But again, we don't have a lot of information.

We do have a little bit more information about the materials that were retained by the Trump administration, by President Trump when he left. We have that famous photo of the sort of files on the floor. And you can see if you look at those pictures, that many of those documents were what's called top secret SCI, which is special compartmented information. That is the most highly classified information the U.S. government has and includes HUMINT, that is human intelligence and special intelligence.

I mean, this is the kind of information that is the most likely to do damage to the U.S. government - again, without seeing the actual documents. Hard to say with certainty, but these are the classifications that are reserved for the material that is the most highly protected set of secrets the U.S. government has.

On Hathaway's suggestion to declassify records after ten years, with very few exceptions, instead of the current policy of 25 years

25 years really isn't working, and so we need to ramp it up, I think, and make it clearer. Also, in my experience, when you look at these documents, the things that are likely to do real damage to national security are about current programs, current events, planned missions and the like. That's the sort of thing where, if you release that information, you really could put individuals at risk, you could put missions at risk, you could put programs at risk. After ten years, that's much less likely. I included within my recommendation as well that anything that has to do with actual individuals – we call them spies colloquially, but somebody involved in human intelligence – that information should be retained as classified for a long period of time. But after ten years, generally, the information is pretty stale. And therefore, there's not as much justification for the U.S. government to continue to keep it secret.

There should be systems in place that encourage individuals to really seriously consider the decision to put a high classification marking. We have technology now that can help with these decisions, we really should be using it. And we should be much more aggressively declassifying information because we're creating, every year, 50 million new documents that are classified, but we're not declassifying anywhere close to that rate. And we could be doing much more when it comes to actually pushing that information back out that no longer needs to be kept classified.

READ MORE  Damar Hamlin’s cardiac arrest has brought fresh attention to NFL players’ contracts. (photo: Lon Horwedel/USA Today)

Damar Hamlin’s cardiac arrest has brought fresh attention to NFL players’ contracts. (photo: Lon Horwedel/USA Today)

Deals for tens of millions of dollars make headlines. But they contain plenty of caveats, and lesser known players are offered few protections

Most of the money isn’t guaranteed

Gaudy headline figures reported in the media when players sign contracts are rarely an accurate reflection of the true sums that will end up in their bank accounts. Take the 10-year, $503m deal agreed by the Kansas City Chiefs’ Patrick Mahomes in 2020.

Only (a word that often deserves quote marks when discussing sports salaries) $141m is guaranteed money. There are so many conditions, outs and “guarantee mechanisms” in Mahomes’ contract, SI.com reported, that it stretches to over 100 pages. In Spotrac’s breakdown of NFL contracts, the guaranteed sum is below the theoretical value of the agreement about 90% of the time. And that’s especially true for lesser players, since they have limited negotiating power.

Signing bonuses are ringfenced in the NFL. Often, however, if a player is cut from a team as a result of injury, underperformance or simply to save money, their contract evaporates. Contrast that with Major League Baseball, where contracts are fully guaranteed: the Los Angeles Angels’ Mike Trout signed a $426.5m, 12-year deal in 2019, every dollar destined for his bank account. Almost all NBA contracts are fully guaranteed. But in the NFL, through no fault of his own a player could find himself unemployed after a year having earned, for example, $1m from what was theoretically a three-year deal worth $3m.

There’s an archaic league funding rule stating that guaranteed money must be placed in escrow. That gives owners a ready excuse to wriggle out of offering guaranteed money, and may discourage cash-strapped teams from big commitments. But really, it’s all a question of negotiating power. “There’s nothing in collective bargaining that says you have to guarantee basketball or baseball contracts, there’s nothing that says you don’t have to guarantee football contracts,” says Andrew Brandt, a former Green Bay Packers vice-president in charge of player contracts.

“NFL owners have continued to use the argument: ‘We can’t guarantee it, it’s an extremely high injury sport, it’s going to hurt our product [to be] paying people who get injured all the time’,” adds Brandt, professor of practice and executive director of the Moorad Center for the Study of Sports Law at Villanova University.

“It’s just been the way it is, even with the most leverage players like star quarterbacks, they’re basically on long-term deals that are really two-year deals – two years guaranteed and the rest is kind of a team option.”

Getting injured often leads to a hefty pay cut

The NFL Network journalist Ian Rapoport reported that Hamlin’s four-year, $3.64m contract was due to earn him $825,000 this season but contained a clause to pay him at a lower rate of $455,000 while on the injured reserve list. In other words: a 45% salary cut because he suffered a cardiac arrest doing his job. And that is pretty standard for injured players.

In a sport this violent, the question is not whether a player will get hurt, but when. According to a 2017 Harvard analysis, the mean injury rate in the NFL is 5.90 injuries a game, compared with 0.45 in MLB, 0.16 in the NBA and 0.59 in the NHL. The enormous health risk means teams don’t want to commit to the kind of long-term, guaranteed deals seen in other sports. But that risk is exactly why financial security is so important to players. They’re expected to play hard all the time – and yet they could be one tough tackle away from a massive loss of earnings. The new collective bargaining agreement (CBA) agreed in 2020 raised the number of regular-season games from 16 to 17 and expanded the playoffs from 12 to 14 teams. And more games means more injuries.

“I’m sure agents are now all going to say: ‘You can’t give me a split [a lower rate while injured], look what happened to Hamlin’. The argument on the other side is going to be, that’s once in a million,” says Brandt. “If they do something unique with that contract there’s going to be a line at the door of every team of players wanting to be treated that way.”

Oh, and be careful if you’re an NFL player out jogging near your home, or sweating on your personal Peloton: it might cost you your $10m salary even if you’re lucky enough to have an injury guarantee in your contract. After Ja’Wuan James suffered an achilles injury at a private gym in 2021, the league warned: “an injury sustained while a player is working out outside of team supervision in a location that isn’t an NFL facility is considered a non-football injury, meaning the injury isn’t covered by the standard contractual injury guarantee.”

No pension before year three

As in the NBA, players are eligible for the NFL pension plan after three seasons – down from four prior to the latest CBA. For eligibility purposes a season means three or more games on a roster. Other benefits are available depending on length of service, such as severance pay and five years of health insurance after retirement. Players can start drawing their full pensions aged 55; the new CBA will reportedly see the average annual pension rise to $46,000.

Healthcare is a contentious issue given the threat of injuries, and the effects of concussions may not be felt until many years after retirement. Disability compensation is up to $265,000 a year, but considering the average career length is 3.3 years according to the players’ association (or six years if a player makes an opening-day roster, per the NFL commissioner), many players do not qualify for the full suite of benefits. In baseball, meanwhile, players become eligible for the MLB pension scheme after only 43 days. The NHL scheme is also structured more favourably to players.

Financial stress is common; a 2015 National Bureau of Economic Research study found that nearly 16% of former NFL players filed for bankruptcy within 12 years of retirement – a far higher rate than in the wider US population.

Ordinary players have little leverage

With 55 players on an NFL roster, there is a vast cast of expendable rank-and-file members beneath the top layer of stars, in contrast to the NBA, where smaller squads magnify individuals’ importance. That makes it harder for ordinary players to agitate for better pay and conditions and may also help explain why basketball has led the way on calls for social and racial justice.

A study by David Niven of the University of Cincinnati found that after the national anthem kneeling protests against racial inequality, “a far greater percentage of protesters [than non-protesters] received a salary cut, that protesters’ overall salaries grew at a notably slower rate, and that protesters were vastly more likely to be sent to another team.”

The former Washington defensive back DeAngelo Hall told The Undefeated (now Andscape) in 2017: “If you had a guy making $100m in the NFL and it was a fully guaranteed contract, he’d probably be able to voice his opinion on several social issues. But the NFL is a year-to-year deal. You could be great one year and not great the second year and you’re in the process of taking a pay cut or getting cut. It’s definitely not LeBron James.”

The salary cap limits wages

The NFL salary cap was introduced in 1994, when it was $34.6m per team. This season it was $208.2m, far outstripping the US inflation rate over that period. Minimum salaries are also on the rise, and will continue to increase each year this decade from the present annual amount of $705,000 for a rookie. But the league’s estimated revenue has soared, too, from $4bn in 2001 to $18bn this year.

The cap is a far stricter limit than in MLB, where teams often sail over the threshold because they’re willing to pay a “luxury tax”. The NFL cap and the accounting rules for prorated bonuses discourage generous contracts because they reduce flexibility for front offices who are wary of having their current and future competitiveness hamstrung by payments to injured, ineffective or former players. That’s the case with the Atlanta Falcons, stuck with $40.5m in “dead money” in 2022 after they traded quarterback Matt Ryan to Indianapolis.

As a collective, the NFL franchise owners are tough and united negotiators and the present CBA runs until the end of 2030, limiting the potential for reforms before then. Still, the astonishing five-year, $230m contract the Cleveland Browns handed the quarterback Deshaun Watson in March 2022 – the most guaranteed money in NFL history – had the feel of a paradigm shift at the time. However, it reportedly drew a backlash from other owners intent on ensuring it remains an outlier. “Those of us in the industry thought this might be a precedent,” says Brandt. “That did not happen. Owners were able to stem the tide.”

READ MORE  Kevin McCarthy said two years ago that Representative Marjorie Taylor Greene would have her committee assignments restored if Republicans won back control of the House. (photo: Haiyun Jiang/The New York Times)

Kevin McCarthy said two years ago that Representative Marjorie Taylor Greene would have her committee assignments restored if Republicans won back control of the House. (photo: Haiyun Jiang/The New York Times)

Some of the former president’s most outspoken defenders will sit on the House’s main investigative committee, underscoring their high-profile roles in the new Republican majority.

Several of the most extreme Republicans in Congress and those most closely allied with Mr. Trump have landed seats on the Oversight and Accountability Committee, the main investigative organ in the House. From that perch, they are poised to shape inquiries into the Biden administration and to serve as agents of Mr. Trump in litigating his grievances as he plots his re-election campaign.

Their appointments are the latest evidence that the new Republican majority is driven by a hard-right faction that has modeled itself in Mr. Trump’s image, shares his penchant for dealing in incendiary statements and misinformation, and is bent on using its newfound power to exact revenge on Democrats and President Biden.

Many of the panel’s new Republican members — including Representatives Marjorie Taylor Greene of Georgia, Paul Gosar of Arizona, Lauren Boebert of Colorado and Scott Perry of Pennsylvania — are among Mr. Trump’s most devoted allies in Congress. Their appointments underscore that, while the former president may be a shrunken presence in the current political landscape, he still exerts much control over the base of his party.

They are also an unmistakable signal from Speaker Kevin McCarthy, who won his post after an excruciating battle with hard-right rebels, that he plans to reward such lawmakers — even some who led the opposition to his election — with high-profile roles.

Mr. McCarthy, who credited Mr. Trump with getting him over the finish line in the speaker’s race, said last week that he would study the idea of expunging the former president’s impeachment record.

“I would understand why members would want to bring that forward,” Mr. McCarthy said at a news conference last week, while outlining other priorities of the new Republican majority. “We’d look at it.”

Both Ms. Greene and Mr. Gosar were removed from congressional committees by Democrats during the last Congress for internet posts that advocated violence against their political enemies. Both also have appeared with Nick Fuentes, the white supremacist and Holocaust denier.

Ms. Greene, who is pressing to impeach Mr. Biden and has demanded an investigation of the treatment of Jan. 6 defendants, had listed the Oversight panel as her first choice. She recently said that if she had led the Jan. 6 attack, “we would have won” and that people would have been “armed.” (She later said she was being sarcastic.) Mr. Gosar has referred to members of the mob that stormed the Capitol as “peaceful patriots.”

Joining them on the panel will be Mr. Perry, who was one of the key figures in Mr. Trump’s effort to subvert the election results, and Ms. Boebert, who has repeated Mr. Trump’s false claims that the election was stolen and came under fire for posting about Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s location on Twitter during the Capitol riot.

The Oversight Committee has long been populated by the most ideological and outspoken members of the House in both political parties, along with those who have less interest in legislating than in landing political blows that will grab the attention of the public and tarnish their opponents.

“We always treated it as a dumping ground for our less serious members,” said Brendan Buck, who served as a top adviser to the past two Republican speakers, Paul Ryan of Wisconsin and John A. Boehner of Ohio. “Republicans have long treated Oversight as the land of misfit toys.”

But with Democrats controlling the White House and Senate, leaving the G.O.P. with little prospect of enacting its right-wing legislative agenda, House Republicans have made it clear that investigations will be their primary focus, giving members of the Oversight panel more relevance.

“There’s very little evidence that members on the far right have moved on from Donald Trump,” said Mr. Buck. “This will be a forum for his grievances and going down ridiculous rabbit holes and entertaining conspiracy theories.”

But the implications go beyond the committee itself and reflect the state of the party, where moderate voices are few and being on the right side of Mr. Trump is still regarded as a necessity. In 2021, eight Republican senators and 139 Republican representatives voted to sustain one or both objections to the election results that made Mr. Biden president.

“It’s a snapshot of where the Republican Party is,” said William Kristol, a prominent Never Trump conservative, referring to the makeup of the House Oversight Committee. “It’s wishful thinking to think there is a healthy Republican Party and this wacky Republican conference. They just got elected. Aren’t they the most representative thing of the party that exists?”

Mr. McCarthy said two years ago that Mr. Gosar and Ms. Greene would have their committee assignments restored, and possibly elevated, if Republicans won back control of the House. “They may have better committee assignments,” Mr. McCarthy said at the time.

The speaker also credits himself with putting people in positions where they can be most successful. He may see a political upside to placing politically motivated firebrands on a committee devoted to investigations that could tarnish Mr. Biden. In 2015, Mr. McCarthy jeopardized his first attempt at becoming speaker by bragging that the House select committee formed to investigate the attack on the American diplomatic mission in Benghazi, Libya, had been successful in damaging Hillary Clinton, the Democratic presidential candidate.

The White House has seized on the elevation of members who have mimicked Mr. Trump’s tactics as the latest example of the Republican Party’s lurch to the extremes.

“Republicans are handing the keys of oversight to the most extreme MAGA members of the Republican caucus who promote violent rhetoric and dangerous conspiracy theories,” Ian Sams, a White House spokesman, said in a statement, referring to Mr. Perry, Ms. Greene, Ms. Boebert and Mr. Gosar. “They have defended and downplayed a violent insurrection against our democracy.”

Mr. Sams added, “House Republican leaders should explain why they are allowing these individuals to serve on this committee and reveal transparently once and for all what secret deals they made to the extreme MAGA members in order to elect a speaker.”

Other new members on the Oversight Committee who have attracted less attention include Representative Russell Fry of South Carolina, who has campaigned with election conspiracy theorists including Mike Lindell, the chief executive of MyPillow; and Representative Anna Paulina Luna of Florida, who has denied the results of the 2020 election and has appeared on a television program that has pushed the QAnon conspiracy theory.

A spokeswoman for Ms. Luna said the congresswoman “has done thousands of hours of media on the campaign trail and as a member of Congress and, being that she works full time, does not obsessively track TV programs.”

It is not yet clear how much latitude lawmakers devoted to Mr. Trump will have to use the panel to do his bidding. Some Republicans have signaled, for instance, that they do not want to relitigate the work of the Jan. 6 committee, as Mr. Trump has made it clear he desperately wants to do, fearing that focusing on the attack and the former president’s actions leading up to it will hurt the party politically.

Representative James R. Comer, Republican of Kentucky and chairman of the Oversight Committee, has said he plans to investigate Mr. Biden’s family and its business connections. He is not seen as an extremist in the conference.

But in his role as chairman, he will have to balance and address the demands of committee members like Ms. Greene, who has already introduced five articles of impeachment against Mr. Biden. That includes one on the day he took office, when she accused him of abusing his power as vice president to benefit his son Hunter Biden’s business dealings in Ukraine.

Mr. Comer “may have claimed that he wanted the committee to be ‘credible,’ but the selection of these members shows this committee is nothing more than a bad joke,” said Brad Woodhouse, a senior adviser to the Congressional Integrity Project, a group dedicated to undermining Republican-led congressional investigations.

In a statement on Wednesday evening, Mr. Comer called Republicans on his panel “an all-star lineup ready to hit the ground running and go to bat for the American people.”

READ MORE  Workers pack orders at an Amazon fulfillment center on January 20, 2015 in Tracy, California. OSHA cited Amazon after federal safety inspectors found ergonomic hazards at three Amazon warehouses. (photo: Justin Sullivan/Getty)

Workers pack orders at an Amazon fulfillment center on January 20, 2015 in Tracy, California. OSHA cited Amazon after federal safety inspectors found ergonomic hazards at three Amazon warehouses. (photo: Justin Sullivan/Getty)

As part of a larger investigation into hazardous working conditions, the Occupational Safety and and Health Administration announced on Wednesday it has cited Amazon for failing to keep workers safe at warehouses in Deltona, Florida; Waukegan, Illinois; and New Windsor, New York.

"While Amazon has developed impressive systems to make sure its customers' orders are shipped efficiently and quickly, the company has failed to show the same level of commitment to protecting the safety and wellbeing of its workers," said Assistant Secretary for Occupational Safety and Health Doug Parker.

The e-commerce giant faces a total of $60,269 in proposed penalties, the maximum allowable for a violation of the General Duty Clause of the Occupational Safety and Health Act, which requires employers to provide a workplace free from recognized hazards.

Amazon has 15 days to contest OSHA's findings.

"We take the safety and health of our employees very seriously, and we strongly disagree with these allegations and intend to appeal," said Amazon spokesperson Kelly Nantel in a statement.

"Our publicly available data show we've reduced injury rates nearly 15% between 2019 and 2021," Nantel added. "What's more, the vast majority of our employees tell us they feel our workplace is safe."

Parker noted that willful or repeated violations by an employer can lead to higher penalties. He said that there are no ergonomic-related violations in Amazon's history that put the company on track for the "severe violator program," but with further inspections, that could change.

In December, OSHA cited Amazon for more than a dozen recordkeeping violations, including failing to report injuries, as part of the same investigation.

Inspectors compared DART rates — days away from work, job restrictions or transfers — across the warehouse industry and at Amazon facilities, and found the rates were unusually high at the three Amazon warehouses.

At the Amazon fulfillment center in Waukegan, Illinois, where workers handle packages in excess of 50 pounds, the DART rate was nearly double the DART rate for the industry in general, and at the Amazon facilities in New York and Florida, it was triple.

The DART rate for the industry in general was 4.7 injuries per 100 workers per year in 2021, Parker said.

Inspectors also found that workers are at risk of being struck by falling materials unsafely stored at heights of 30 feet or higher at the Florida facility.

Should the government prevail, Amazon would be required not only to pay the fines but also to correct the violations, which Parker noted, could result in significant investments in re-engineering their processes to provide workers with a safer working environment.

READ MORE  Investor-state dispute settlements increasingly allow oil and gas investors to sue countries over their climate policies. (photo: Andrew Burton / Getty)

Investor-state dispute settlements increasingly allow oil and gas investors to sue countries over their climate policies. (photo: Andrew Burton / Getty)

Investor-state dispute settlements increasingly allow oil and gas investors to sue countries over their climate policies.

However, the energy company backing the project didn’t take no for an answer: TransCanada soon sued the U.S. for $15 billion dollars — the future expected profits it claimed the pipeline would have earned, in addition to the $3.1 billion it had already invested in the project. The company was able to do so because the North American Free Trade Agreement, the treaty known as NAFTA that the U.S. signed with Canada and Mexico in 1994, included a clause about something called an investor-state dispute settlement, or ISDS — a closed-door legal process that’s an often overlooked, but increasingly urgent, hurdle to addressing climate change. ISDS mechanisms are included in many other bilateral and international trade agreements, allowing a country to be sued by investors from other member countries if it takes any subsequent actions that adversely affect those investments.

The threat of this liability has hung over the pipeline conflict ever since: When President Trump signed an executive order in 2017 reversing course and allowing Keystone XL to move forward, TransCanada announced that it would suspend its ISDS case against the U.S. for 30 days — exactly the deadline for the decision on their new permit application. In March of that year, the new permit was approved, and TransCanada dropped its ISDS claim.

Corporations’ ability to threaten this kind of financial liability is creating growing problems for countries looking to tackle climate change and restrict fossil fuel extraction, says Kyla Tienhaara, the Canada Research Chair in Economy and Environment at Queen’s University in Ontario. It’s far from the only recent example: Take Italy, which banned oil drilling within 12 nautical miles of its coast only to be sued by the UK-based oil company Rockhopper, which had hoped to develop a near-shore oilfield at Ombrina Mare, off the coast of Abruzzo. This summer, an international tribunal authorized to adjudicate investor-state disputes ordered the Italian government to compensate the firm $210 million pounds.

Tienhaara and her colleagues recently published a study in the peer-reviewed academic journal Science finding that global efforts to limit new oil and gas developments could generate as much as $340 billion in legal claims from fossil fuel investors seeking to recoup their losses. (To put this in perspective, the Green Climate Fund, an international mechanism established to help developing countries adapt to climate change, has a portfolio valued at $11.3 billion.) Already, fossil fuel industries represent a large and growing number of the plaintiffs in these kinds of disputes: In 2020, around 20 percent of ISDS cases were brought by oil and gas companies.

These settlements are decided in a private legal process. Unlike public judicial systems, these tribunals are typically run by three arbitrators chosen jointly by the disputing parties. These people tend to be repeatedly selected from a small group of experts in corporate law, and at times they act as lawyers for an investor in one case and arbitrators deciding the case in another, though the cases may be similar or even simultaneous — a practice known as “double hatting.”

Because ISDS systems are written into thousands of different treaties, each with different wording, there’s also no system of precedence. Just because arbitrators decide something in one case doesn’t mean that logic has to be applied to another. Proceedings can be kept confidential, and there is no way to appeal a tribunal’s decision.

Tieenhaara argues that the specter of being sued for making decisions that inhibit the profits of companies and investors has a chilling effect on countries’ efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. New Zealand, for example, recently said that it could not join the Beyond Oil and Gas Alliance, an international consortium of governments working to phase out fossil fuels, because doing so “would have run afoul of investor-state settlements.” Countries in the developing world are even less able to afford the fiscal risk of being on the hook for lost profits.

As of 2017, the average amount awarded in an ISDS case was $504 million. Recently, however, there have been some exorbitant outliers, like a 2019 case in which Pakistan was ordered to pay $5.9 billion to the Australian Tethyan Copper Company for lost future profits after the country denied its lease. (The company had only invested about $150 million in the project to date.) The decision, which came down just one week after the International Monetary Fund approved a loan of almost exactly the $6 billion Pakistan was about to lose, represented the equivalent of 40 percent of the country’s cash reserves in foreign currency.

The annual United Nations conference COP27 concluded in November with a broad agreement that wealthy, developed countries have a financial obligation to support poorer countries that have contributed relatively little to causing climate change as they adapt to its consequences. Yet those latter countries also bear the majority of the financial risk stemming from potential ISDS claims. Tienhaara recently worked on an analysis, published in the peer-reviewed journal Climate Policy in December, which found that the developing world faces enormous liabilities if it cancels potential fossil fuel projects. Mozambique, for instance, which has substantial offshore gas reserves, currently has an ISDS risk of $29 billion — nearly twice its annual national income.

“The system is unbalanced toward investors,” said Lea Di Salvatore, a legal researcher at the Columbia Center on Sustainable Investment, affiliated with Columbia University. Di Salvatore recently analyzed 29 of Mozambique’s gas, coal, and oil projects and found the majority are protected by ISDS clauses. “Are we really expecting Mozambique to take action against TotalEnergies or ExxonMobil, who have all the political and economic power?” Tienhaara added that many other African countries are in a similarly precarious position, forced to choose between climate action and expensive payouts.

There are at least 2,500 investment treaties globally, many written with decades-old policy priorities in mind. Supporters of these international agreements suggest that they provide legal stability that can spur investors to commit to useful projects that might not otherwise find funding — including those critical to renewable energy development. But the Columbia Center on Sustainable Development argued in a December report that investment treaties “are neither effective nor decisive in attracting investment in renewables to developing countries.”

Instead, the authors recommend governments focus on establishing internal regulatory frameworks and strengthening domestic judicial systems to protect investors. Tienhaara believes that states should go further by taking steps to terminate existing treaties and developing binding rules to limit the amount of compensation that can be awarded to investors.

The Energy Charter Treaty, or ECT, which has been ratified by over 50 primarily European countries, is the international agreement that’s the largest hurdle to enacting policies to combat climate change. Signed in 1993, it explicitly aims to protect the energy investments of its members. Historically, many investor-state disputes resulted in rulings favoring companies based in rich countries. But thanks to the ECT, European countries have recently found themselves on the receiving end of ISDS claims more frequently.

This year, many appeared to reach a breaking point. Poland announced this fall that it would withdraw from the ECT; Spain, France, Germany, the Netherlands, and Slovenia followed. In late November, the Council of the European Union failed to reach an agreement on modifications to the treaty to bring it into alignment with Paris Agreement climate targets that came into force in 2016. Instead, the European Parliament called for a coordinated European Union departure from the treaty altogether.

Yet these countries may still be on the hook for claims under the ECT for another 20 years. That’s because the treaty, like many agreements with ISDS provisions, includes a “sunset clause” that extends its protections long after a state’s withdrawal. The United States is facing just such an issue currently: Though NAFTA expired in 2020, it included a sunset clause allowing investors to file disputes for three additional years. When the Biden administration canceled the permit for the Keystone XL pipeline once again in 2021, the company behind the pipeline brought back its ISDS claim. A tribunal to settle the matter was recently appointed, and the process is ongoing even as the pipe system the project would have extended gushes tens of thousands of barrels of oil into a creek in Kansas.

Advocates like Tienhaara say the recent signs of movement away from agreements like the ECT are promising, but many ISDS cases stem from countless other bilateral treaties, which likely need to be addressed individually.

Ultimately, Tienhaara argues that investor certainty should not be prioritized above climate action. “Climate change is a global problem,” she said. “We need to care about everyone, everywhere — and have policies that aren’t just about defending our own interests.”

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.